State Law, Local Interpretation: How Cities Are Implementing Senate Bill 9

Published On June 8, 2022

Introduction

Last year, Governor Gavin Newsom signed the California Housing Opportunity and More Efficiency (“HOME”) Act, otherwise known as Senate Bill 9, which was introduced by the Senate President pro Tempore Toni Atkins. This new law enables homeowners to split their single-family residential lot into two separate lots with each able to hold up to two homes. If utilized to its full potential, this law allows owners to create up to four units of housing on what was previously only a single-family home. The legislation represents a potentially sweeping change in a state that has historically held vast amounts of land for single-family only uses. However, recent media coverage has shown that localities may be taking advantage of the bill’s broad language to implement the HOME Act in ways that would limit the number of new homes built. A recent, extreme—and ultimately unsuccessful—example came from the city of Woodside, where council members proposed establishing the town as a mountain lion sanctuary to claim that the HOME Act did not apply to their community. The Attorney General pushed back, declaring that such a policy would not exempt the city from state housing law. Other localities have implemented less obvious—and likely more legally defensible—restrictions that may stymie meaningful new homebuilding as a result of the new law.

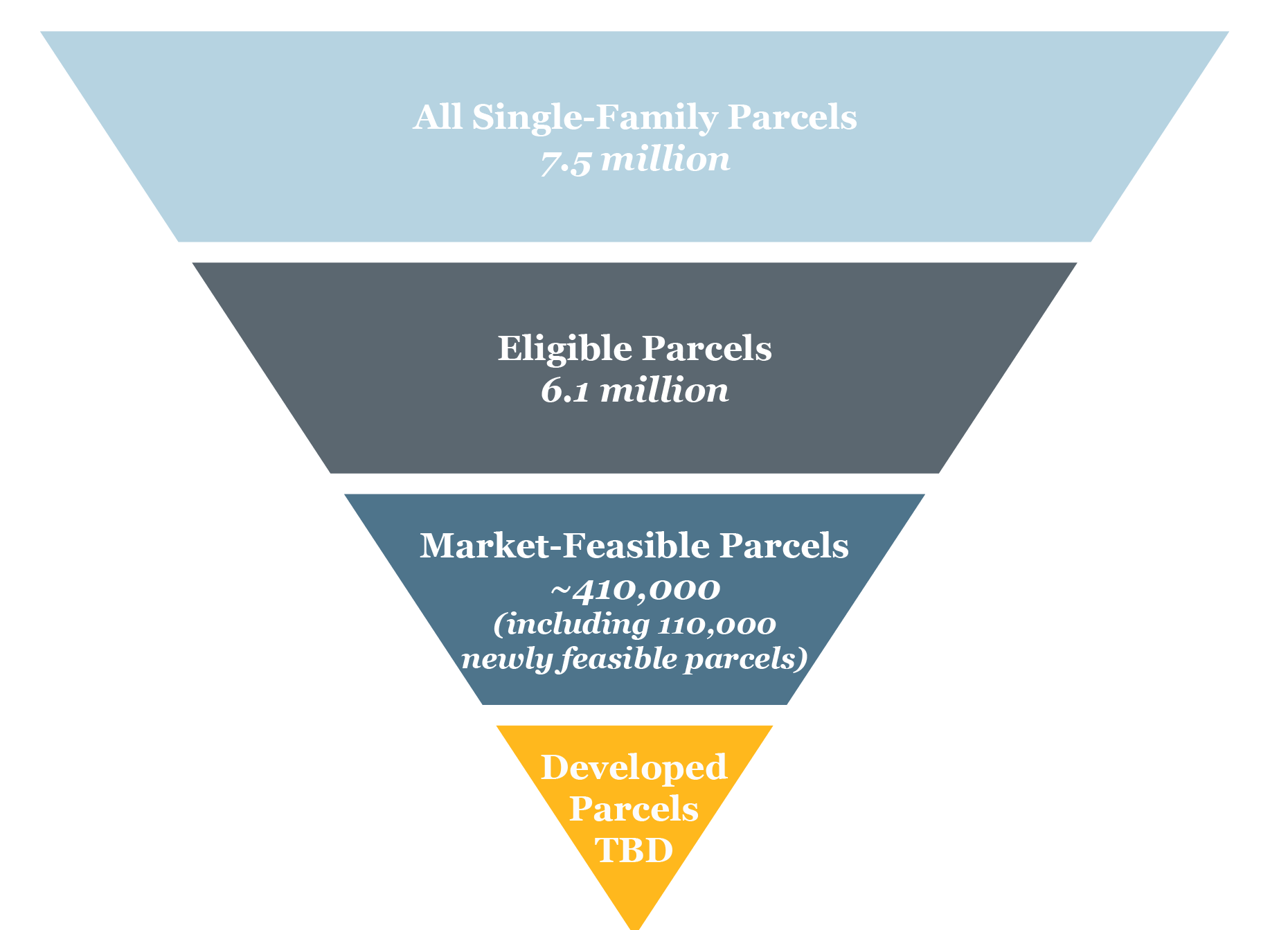

A 2021 Terner Center analysis estimated that the HOME Act could enable the creation of 700,000 new market-feasible homes throughout the state (Figure 1). As the report emphasized, however, this number is contingent on property owner interest and construction costs as well as contingent local factors such as adequate contractor capacity and availability of appropriate mortgage products. Central to these dimensions is the degree of support from local jurisdictions: the ways that localities implement this law will have a significant impact on new homebuilding enabled by SB 9. As designed, SB 9 allows jurisdictions to implement the law using their own objective design standards and limitations and allows for the imposition of additional restrictions outside of a broad baseline of requirements as laid out in the bill. These loose conditions have created a massive statewide laboratory of sorts, with over 500 local jurisdictions that each have an opportunity to implement the HOME Act in their own unique ways. In the cities we examined, no two ordinances were alike. In addition, homeowner associations are allowed to ban SB 9 lot splits—a practice outlawed for statewide ADU standards—thereby allowing some organizations at the most local level to further limit unit feasibility.

Figure 1. Senate Bill 9 Parcel Development Funnel (Total Numbers) from 2021 Terner Analysis Source: 2021 Terner Center report on the potential impact of SB 9 on new housing supply by modeling the financial feasibility of new home construction.

Source: 2021 Terner Center report on the potential impact of SB 9 on new housing supply by modeling the financial feasibility of new home construction.

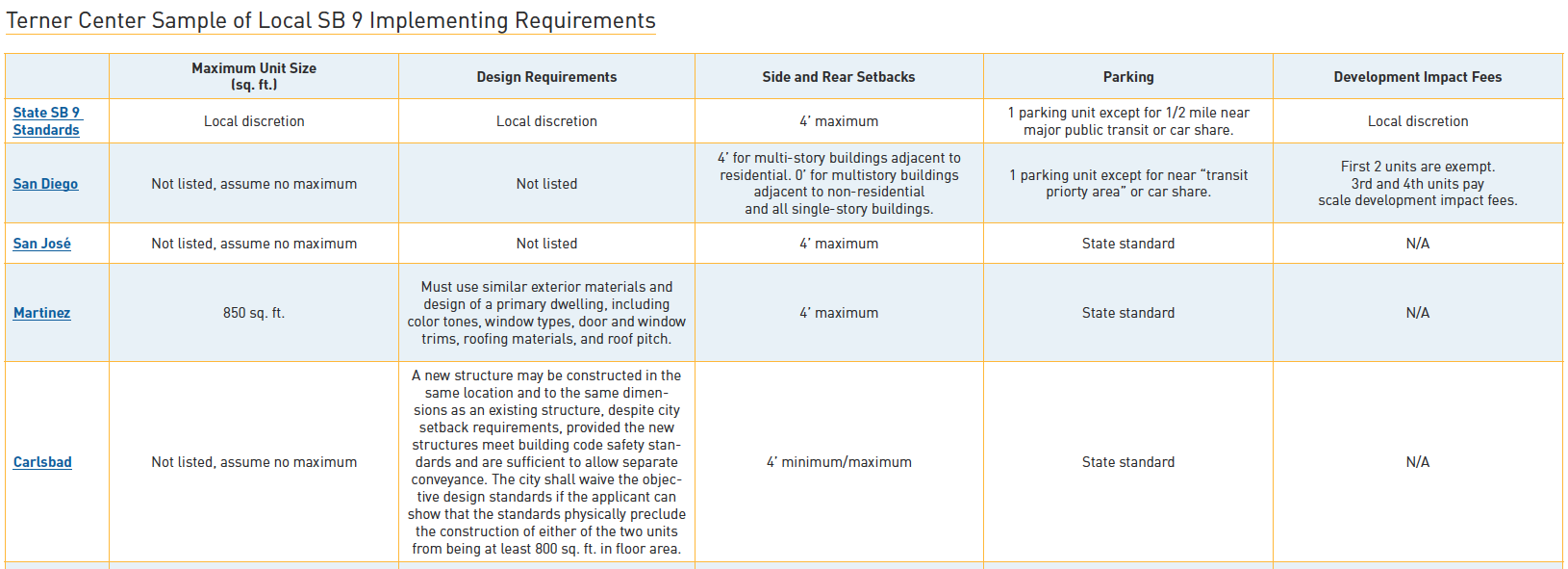

The following analysis looks at how cities are implementing SB 9 differently and explores how these regulations might facilitate new home construction or hinder it. To better understand how each city’s specific requirements might impact SB 9 uptake, we examine 10 cities with SB 9 implementing ordinances. The cities were selected based on size and geography to reflect different types of communities. A majority of cities in the Central Valley and Inland Empire have not adopted SB 9 ordinances at this time and, therefore, are not included in our analysis.

This analysis presents an opportunity to assess the different implementation strategies of different cities and to analyze how future state-mandated land use rules might be adopted locally. It is not intended to be a ranking, but rather an examination of how major statewide land use laws may be adopted later by local jurisdictions.

Background: State Law, Local Interpretation

SB 9 sets a baseline standard that all localities must follow with regard to the law’s implementation. The bill locks in certain standards, such as minimum building structure size allowed (800 sq. ft.) and lot size requirements (in a lot split, each new lot must be at least 1,200 sq. ft. in size or 40 percent of the existing lot size). Local jurisdictions cannot pass standards that exceed a 4 ft. maximum rear and side setback, which is the minimum distance between the edge of a property and the structure. For parking, localities may require one parking space per unit unless the lot is within 0.5 miles of a high-quality transit corridor, a major transit stop, or within one block of a car share vehicle. The law does not apply to homes in historic and landmark districts, very high fire hazard zones1, flood zones, prime farmland, and environmentally-protected areas. The HOME Act also requires that the local review process for a SB 9 lot splits must move from discretionary review (i.e., subjective, case-by-case) to ministerial approval (i.e., objective, consistent application).

Outside of these requirements, local jurisdictions generally have significant discretion on the additional regulations that they can impose on SB 9 projects. While SB 9 does state that local requirements may not “physically preclude” the development of a duplex, in practice, localities could pass objective design standards, affordability requirements, or use of land requirements that would result in projects which are technically eligible under the law but are rendered economically infeasible by the requirements.

Unit Design Requirements

We found wide variation in the allowable size and height of SB 9 units. Carlsbad does not have a height limit or maximum unit size listed. San José and San Diego have lenient height maximums of up to 30 ft. without a maximum unit size requirement. These limits track with general trends for single-family homes across the state: the median height limit for single-family homes that we observed in our California Residential Land Use Survey is 30 ft., whereas the median height for multifamily is 35 ft. On the other hand, Beverly Hills and Walnut Creek have a height restriction of 14 ft. Six out of ten cities in our analysis implemented height requirements under 20 ft. Moreover, many of these cities have made the maximum size for new units close to the minimum size required by the state law—800 sq. ft. Such requirements will almost certainly limit the number of lots that will be effectively eligible for new building under SB 9.

In addition to size and height, jurisdictions are also implementing other design requirements. For example, Temple City requires a Spanish colonial design and specifies the exact size and materials needed for the building. Dictating specific allowable exterior materials and architectural designs can increase the cost for new units. It can also limit the use of more affordable construction methods like modular and prefabricated housing units.

Affordability Requirements

We found some cities have imposed affordability requirements that are likely to limit uptake of SB 9. In our analysis, the cities of Sonoma, Los Altos Hills, Temple City, and Beverly Hills require deed-restricted affordable housing for HOME Act projects. Additionally, two localities require deed-restricted affordable housing while also requiring affordable impact fees on these same projects. For example, Sonoma has an impact fee for SB 9 projects while also requiring that one of the units be affordable. Localities usually exempt affordable housing impact fees on affordable projects to help facilitate and reduce the cost of their construction.

Such requirements can be well-intended, but deed-restricted affordable housing requirements may make it challenging—or impossible—for projects to financially pencil without subsidies or offsets. As we have explained in previous work, underlying market conditions such as construction costs and rents play the largest role in determining project feasibility. Requiring affordability in certain projects without commensurate cost offsets can render development infeasible. These same principles apply to smaller developments like SB 9 lot splits, where the limited revenue and financing options created by mandatory deed-restrictions can severely limit where SB 9 projects can pencil out. Moreover, deed restrictions require technical expertise to navigate the regulatory requirements of affordable housing, creating another barrier to homeowner uptake.

Use of Land Requirements

We also found that four out of ten cities in our sample require significant easements—a legal right for a person or entity to access a property owned by someone else for a limited and specific purpose—or other land uses that may significantly limit the uptake of SB 9 by spatially constraining what can be built.

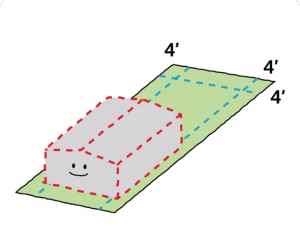

One example of an additional land use constraint is the addition of setbacks that go beyond the requirements set by state law. Requirements at the state level mean that SB 9 lot splits must have a maximum of 4 ft. setbacks at the rear and side of new properties, as illustrated in Figure 2. Though there is no state requirement on front setbacks, some cities have implemented larger front setbacks. For example, Los Altos Hills requires a 40 ft. front setback, which greatly limits parcel eligibility. High front setback requirements can be difficult to meet for SB 9 projects, particularly for smaller lots. As a point of reference, the median front setback according to our statewide survey is 20 ft. for single-family homes.

Figure 2. Side and Rear Setback of 4’, the Maximum Allowed Under SB 9

Source: Image courtesy of United Dwelling.

Source: Image courtesy of United Dwelling.

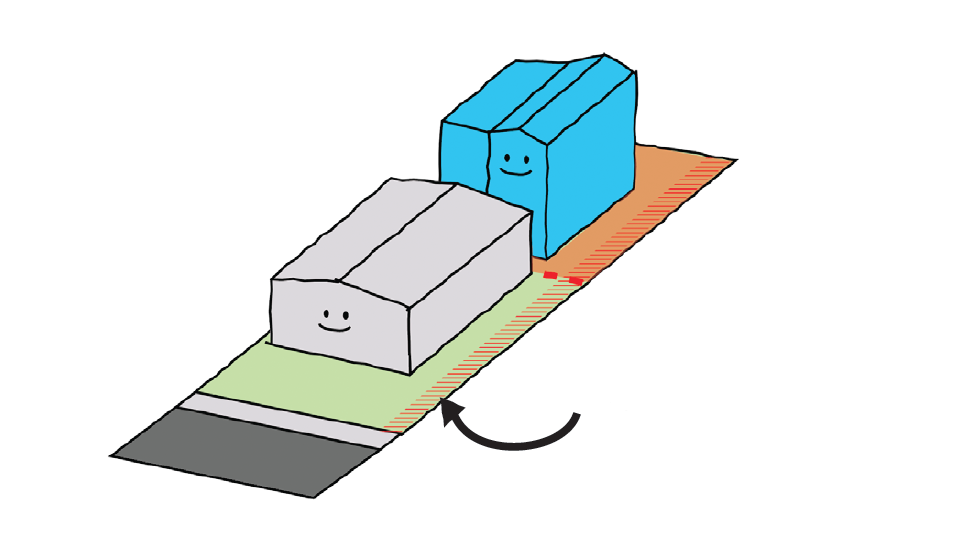

Limitations on the ability of homeowners to create a flag lot where a narrow driveway is placed on the side of two properties to allow an easement—or pedestrian or vehicular access—to the back property from the street are another set of practices that may reduce SB 9 uptake. When properties can be split in a way that results in one unit in the front and one in the back, a common and easy practice is to create a flag lot through the two properties, which allows the property owner to adhere to the easement and maximize the size of each lot.

However, some local requirements have banned flag lots or have required sizable easements that can be difficult to adhere to depending on the size and shape of the lot (illustrated below in Figure 3). Geometrically, requiring a sizable easement while banning a flag lot means the size of a property needed to adhere to these restrictions is quite substantial. Easements larger than necessary for a vehicle to drive in can also prevent development by making smaller lots infeasible to build on. For example, San José’s easement requirement of 12 ft. disqualifies parcels across the city from SB 9 compliance. By contrast, other cities either have large easement standards or do not have a stated policy in their SB 9 ordinance. Some cities, such as Sonoma and Beverly Hills, have banned flag lots altogether.

Figure 3. Flag Lot Created by Easement

Note: Infographic illustrates how a flag lot is created through an easement, with the arrow pointing to the created easement. Source: Image courtesy of United Dwelling

Note: Infographic illustrates how a flag lot is created through an easement, with the arrow pointing to the created easement. Source: Image courtesy of United Dwelling

Parking requirements are another area where local ordinances vary greatly. For example, car-dependent Temple City has both eliminated off-street parking and restricted on-street overnight parking passes for residents of SB 9 units. Applicants are required to have their driveways removed and the curb-cuts removed and repaired. For SB 9 constructions, Los Altos Hills requires one uncovered parking space located a minimum of 40 ft. from the front parcel line and 30 ft. from the side and rear parcel lines. Such parking requirements can discourage development.

Open Space Requirements

Five out of ten cities included in our analysis, including Sonoma and Temple City, require open spaces or courtyards between SB 9 units. Temple City requires a courtyard of 125 sq. ft. or 25 percent of parcel space (whichever is less) between the SB 9 structures. Sonoma requires a 600 sq. ft. area per unit to not be occupied by structures, parking, or driveways and to be shared by both units. Additionally, landscaping requirements, such as those mandating mature trees and large hedges, add to development costs, leading to potentially fewer SB 9 units being financially feasible if they are built at all. Los Altos Hills, Temple City, Goleta, and Sonoma all have specific landscaping requirements. Sonoma requires at least three mature trees and ten shrubs to be planted. Los Altos Hills requires a hedge—sized at 15-gallon minimums and placed at 5 ft. intervals—to surround the property. Goleta’s ordinance asks for at least one 15-gallon size plant for every 5 linear ft. of the exterior walls or a 24-inch box plant for every 10 linear ft. In contrast, San Diego and Walnut Creek require a landscape design that adheres to its standards for single-family homes, requiring no additional requirements for SB 9 properties.

In summary, we found that among the ten cities, seven of them require objective design standards for SB 9 splits that have stricter requirements than for single-family homes or Accessory Dwelling Units. SB 9 requires that local agencies modify or eliminate local standards on a project-by-project basis if objective standards would prevent an otherwise eligible lot from being split or prevent the construction of up to two units at least 800 sq. ft. in size. Local objective design ordinances, which can be hard to adhere to and which can make it more challenging to build, can create a legal loophole that moves away from the intended ministerial approval and reverts the process of splitting a lot to a project-to-project local review standard.

Policy Recommendations

Challenges in state land use laws are not unique to SB 9. When the state first legalized ADUs statewide, unit design requirements, affordability requirements, and use of land requirements hindered their production for years. In California’s 2019 ADU legislative package, the state standardized development fees, permit timelines, unit sizes, and height to create a lasting effect on the housing market. A recent Terner Center survey on newly-constructed ADUs found that most units were available to those making less than 80 percent of the area median income (AMI). However, the overall affordability varies significantly by county. By implementing, in some cases, stricter or more expensive SB 9 standards than would otherwise be required for ADUs, localities may be functionally precluding more housing that is affordable to people hoping to move into the area. Currently, the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD) plans to send letters to 30 local jurisdictions requesting a plan to become more compliant with the intent of SB 9. The Attorney General has threatened to sue localities that outright oppose the new law, most notably in response to the ordinances adopted by Woodside and Pasadena. These actions will likely help shift local policies. Our analysis suggests, however, that the law may need to be expanded upon in a manner similar to ADU laws.

While this analysis has demonstrated some of the challenges of making impactful changes to state housing laws, there are tools and policy changes at both the local and state levels that can help to ensure that SB 9 achieves its goals. With limited budgets and competing priorities, local governments may understandably be struggling to develop an implementing ordinance for a housing law that only became effective in January of this year. Localities have the option to adopt state law as-is without the pressure of implementing a local ordinance. For localities that want to ensure that SB 9 is able to achieve its full potential in catalyzing new housing in single-family neighborhoods, local jurisdictions and the state should take steps to properly implement with the intention of the law and to ensure that SB 9 developments will happen. HCD has released a technical assistance fact sheet to assist local governments with HOME Act implementation. The Association of Bay Area Governments provides local jurisdictions with SB 9 templates such as draft staff reports, PowerPoint presentations, overview graphics, architectural drawings, and ‘missing middle’ housing workshops.

Localities and the state should work to implement the following best practices to help increase parcel eligibility, coordinate municipal services, and help empower homeowners to utilize the full extent of the law, enabling SB 9 to more widely catalyze new housing.

- Localities should provide residents with access to eligible parcel information, easy-to-read checklists, and clear information on project timelines, which would greatly assist homeowners in building a new unit or splitting a lot under HOME Act.

- The state should begin to track SB 9 developments statewide through a system like the Annual Progress Report and introduce bill language to clarify local SB 9 implementation, similar to what has been done to ADU development.

- Local jurisdictions may wish to empower homeowners and small developers by adopting best practices from ADUs and SB 9 adoption ordinance, including such successful policies and programs such as San José’s pre-approved housing designs and same-day permitting approvals.

- Local jurisdictions could also explore directly financing some SB 9 projects to focus on affordability, as the city of Pasadena has done through their ADU construction loan program. Oakland’s nonprofit-driven Keys to Equity program provides a model for assisting low- to moderate-income homeowners with ADU construction as well.

Localities have the ability to ease the housing shortage and create more construction jobs by leaning into new land use laws, developing more community builders, and incubating nonprofit and for-profit small builder startups.

While this analysis is specific to California, it also offers instructive lessons for other states and communities around the country that are working to open up single-family–zoned communities to more housing types. It also highlights the challenges the Biden administration will face as it works to encourage communities around the country to relax exclusionary land use and zoning requirements through preferential scoring in economic and transportation funding programs as well as proposed planning grants.

The extent to which SB 9 will impact housing production across the state is dependent on its effective implementation by local governments. By mandating requirements that hinder the feasibility of housing construction, localities may upend the law’s intended ministerial review and force a reversion to a project-by-project one. Fortunately, state and regional governments are assisting localities with resources for implementation and holding localities accountable for not administering the HOME Act. Local governments should rely on these resources and best practices to ensure that the housing production potential of the law is realized.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our sincerest thanks to everyone who contributed to and reviewed this analysis. We are grateful to the San Francisco Foundation for their support on Terner Center’s HOME Act local implementation work.

This research does not represent the institutional views of UC Berkeley or of Terner Center’s funders. Funders do not determine research findings or recommendations in Terner Center’s research and policy reports.

Footnotes

- There are exceptions to when SB 9 would apply to high fire zones, such as when units are built to higher development standards or local jurisdictions independently decide to allow SB 9 projects in these areas.