Crisis, Response, and Recovery

Published On March 31, 2021

A new study explores how federal policy following the Great Depression and Great Recession helped to forge and reinforce disparities in access to homeownership and wealth building for Black households. Crisis, Response, and Recovery: the Federal Government and the Black/White Homeownership Gap emphasizes that the federal government must not only act with urgency to address the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic but also chart a path to economic recovery that works to dismantle the enduring effects of racism and systemic inequities in the housing and mortgage markets.

Below read a summary blog from the author, our Faculty Research Advisor Carolina Reid, which offers a commentary on how the findings are relevant to the current COVID-19 pandemic and economic crisis and the role that the Biden-Harris Administration is poised to take in response.

Since coming into office, the Biden-Harris Administration has shown the promise of the federal government to address economic crises. The American Rescue Plan, signed into law on March 11, represents a bold and comprehensive response to the economic downturn precipitated by the COVID-19 pandemic, and includes direct aid to impacted families, support for small businesses as well as local and state governments, and relief for renters at risk of eviction. And the recently released $3 trillion infrastructure bill further shows the Administration’s intent to invest in critical sectors of the economy, including climate change mitigation. These actions signal, perhaps, an end to the abiding belief that government is the problem, and instead chart a course where the federal government works to ensure that the benefits of economic growth are widely shared.

How that course is drawn, however, has significant implications for racial justice. Our nation’s history shows that responses to past crises have not led to racially equitable recoveries. This is particularly true in housing policy, wherethe government has been complicit in racial discrimination, or has done little to tackle racial segregation, leading to a continued dual housing market for White and Black households. Indeed, housing remains a central axis by which racial inequality is produced and sustained. In the report we released today, Crisis, Response, and Recovery, I explore how federal policy following both the Great Depression and the Great Recession helped to forge and reinforce disparities in access to homeownership for Black households. It is a story that has been told before, but it has particular resonance now. If the Biden-Harris administration is committed to its racial equity agenda, it must not only act with urgency to address the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, but it must also chart a recovery that directly works to dismantle Black exclusion and undo the enduring effects of racism in housing and mortgage markets.

The analysis in the brief shows that despite the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968, which made racial discrimination illegal, systemic racism in housing and mortgage markets continues to shape access to homeownership for Black households. Nowhere is this more evident in the targeting of subprime loans to Black communities in the 2000s and the inadequacy of the federal response that followed. While on the surface “race-neutral”, the federal government’s unwillingness to invest in significant borrower relief, particularly in Black neighborhoods hardest hit by concentrated foreclosures, meant that investors and higher-wealth households were able to step into the vacuum and benefit from rising property values during the recovery.

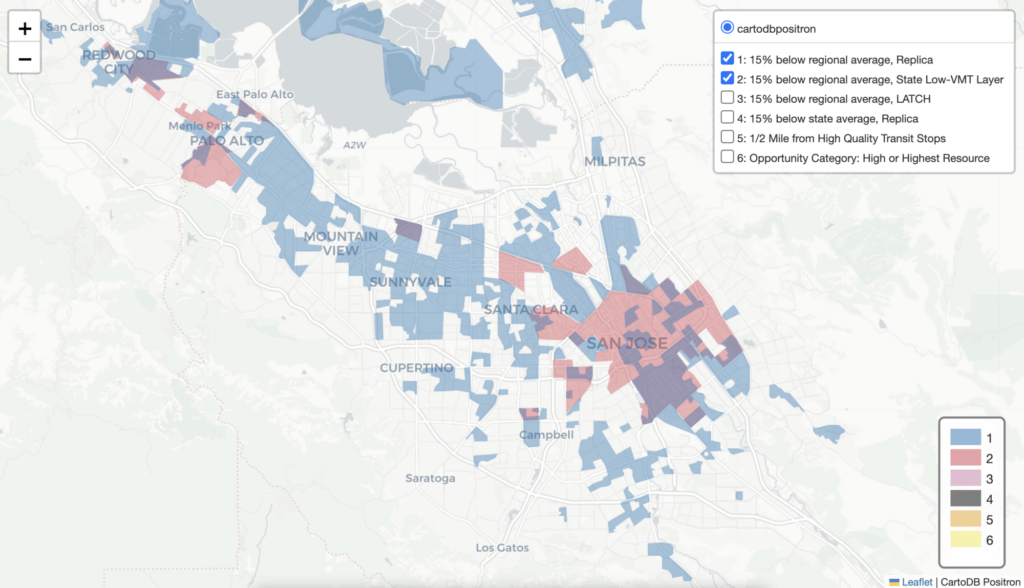

An appendix available here presents data on these dynamics for 50 of the largest metropolitan areas in the United States, highlighting the continued salience of racial segregation. In most places, the White-Black homeownership gap has widened since 2000, demonstrating the consequences of the subprime boom and bust for Black communities. In addition, although there is variation across metropolitan regions, neighborhoods with at least 50% Black residents had higher rates of foreclosure and higher rates of investor purchases (especially for lower-valued properties), and lower house values than neighborhoods with fewer Black residents. In some markets, such as the San Francisco Bay Area, Los Angeles, Raleigh, and Nashville, Black neighborhoods that saw significant drops in mortgage access saw larger price appreciation gains, contributing to gentrification pressures.

What are the policy implications of this research? Certainly, we need to do everything we can to keep people in their homes. The American Rescue Act, which includes nearly $50 billion for housing and homelessness assistance, as well as a continued commitment to preventing evictions, is critical to ensuring that the pandemic doesn’t lead to increased housing insecurity and homelessness. To support distressed homeowners, the Act allocates $10 billion for a Homeowner Assistance Fund, which allows states to provide funds to homeowners for a broad range of needs.1 The legislation stipulates that 60% of the funds need to go to homeowners earning less than the area median income, but it is incumbent on the states to ensure—and the federal government to oversee—that these funds reach Black and other homeowners of color who have been disproportionately affected by the COVID-19 pandemic.

This emergency aid must also be paired with a longer-term federal approach that tackles the underlying system of disparities linked to race and ethnicity in housing and credit markets. Anti-Black racism persists throughout the continuum of homeownership access and the benefits it confers: from disparities in credit scores and wealth, to mortgage access and loan pricing, to tax benefits, and, as has been increasingly apparent in recent months, to the valuation of homes in Black neighborhoods. While the focus in this brief is on Black households and communities, the structural racism that continues to shape Black disadvantage negatively affects Hispanic/Latinx and Asian communities as well, as evidenced by the disparate impact of both foreclosures and the COVID-19 pandemic for these groups.

Two key principles should underpin the federal government’s approach to racial equity in homeownership policy. First, the federal government must redress the repercussions of redlining on Black households and communities. Undoing the inherited disadvantage of past discriminatory housing policies will require new programs in which the federal government explicitly helps Black borrowers overcome the barriers posed by lower credit scores and net worth. The federal government should develop new affirmative credit programs—for example, through the Community Reinvestment Act, the GSEs, and/or FHA—that increase access to sustainable homeownership through fairly priced mortgages and post-purchase financial support. And, it should strengthen the enforcement of fair lending laws as well as the work of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, to prevent discrimination and predatory financial practices.

Second, the Biden-Harris Administration should prioritize reforming the systems that work to perpetuate residential segregation and that exclude or displace lower-income households of color from the neighborhoods they want to call home. As Ta-Nehisi Coates has argued, failing to address the roots of residential segregation merely sets up recurring opportunities for capital to extract wealth from Black communities. The Biden-Harris Administration has already taken steps towards opening up exclusionary communities, recommitting to the Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing (AFFH) rule and the disparate impact standard. But investing in Black neighborhoods is equally important. For example, the federal government should expand funding for mission-based entities to build and preserve affordable housing as well as catalyze the expansion of community land trusts and cooperative ownership models rooted in Black grassroots leadership.

Inequalities in homeownership and its financial benefits are related to a much broader system of disparities linked to race and ethnicity, including tax policy, labor market vulnerability, social service provision, and education, meaning that closing the homeownership gap is not a panacea for racial equity. But it is an area in which the federal government has both the power and responsibility to undo past harms.

Read more findings and recommendations from the paper, and refer to the appendix with the data from 50 of the largest major metropolitan areas, on our website here.

- Eligible uses of the funds include: mortgage payments; principal reduction; interest rate reductions; funds to reinstate a mortgage after forbearance, delinquency or default; payment assistance for utilities, internet, property taxes, homeowners insurance, mortgage insurance, flood insurance, condo fees and homeowner association fees; and a catch-all for “any other assistance to promote housing stability.”