Taking Housing Solutions from the Near-Term Crisis to the Long-Term Crisis

Published On October 25, 2021

It has been over a year-and-a-half since the U.S. economy lost over 20 million jobs in only a few months. Despite months of job growth and recovering employment rates, there are still over 5 million fewer jobs than there were before the pandemic hit. However, this sharp decline in employment, disproportionately felt by renters, did not result in an increase in evictions. Before the pandemic, eviction filings usually averaged over 2 million annually, with nearly 1 million evictions executed. During the pandemic, filings were approximately halved, relative to 2019. Federal, state, and local eviction moratoria, coupled with the rollout of Emergency Rent Relief programs have played important roles in staving off a spike in evictions during the crisis. In addition, landlords changed their management practices during the pandemic, responding both to the financial stresses of their renters and the changed policy environment. Understanding how landlord practices shifted during the pandemic can provide longer-term lessons in how to sustainably reduce evictions beyond the current crisis.

We chart changes in management practices by drawing on two surveys of landlords of small rental properties (1- to 4-unit buildings and rented condos). We fielded the first survey before the pandemic in mid-2019 and the second during the pandemic in the first quarter of 2021. In both we also conducted in-depth interviews with landlords to better understand their management practices and motivations. Together these surveys illustrate the ways in which landlords dealt with missed rent payments before the onset of the pandemic and after, and what their experiences and insights suggest for policy moving forward. We find that, before the pandemic, smaller-scale landlords often worked with tenants who missed a rent payment to bring them current and avoid eviction. This flexibility increased during the pandemic, even as many owners saw their rent revenue decline. This shift was a result of the changes in policy, but also the result of owners responding to the on-the-ground reality of many tenants suddenly losing income during the pandemic.

How did owners of small rental properties deal with missed rent before the pandemic?

As other scholars have noted, many landlords of small rental properties, particularly those with smaller portfolios, work with their tenants to get them current, avoiding the eviction process if possible. Our survey confirmed that this is the case. In the 2019 survey we fielded to owners of 1- to 4-unit rental properties, 20 percent of owners experienced a missed rent payment in the previous two years at a given property. Among these owners 85 percent reported that they first tried to get in touch with the tenant. Nearly 20 percent reported that they responded “by doing nothing and waiting for the tenants to pay.”

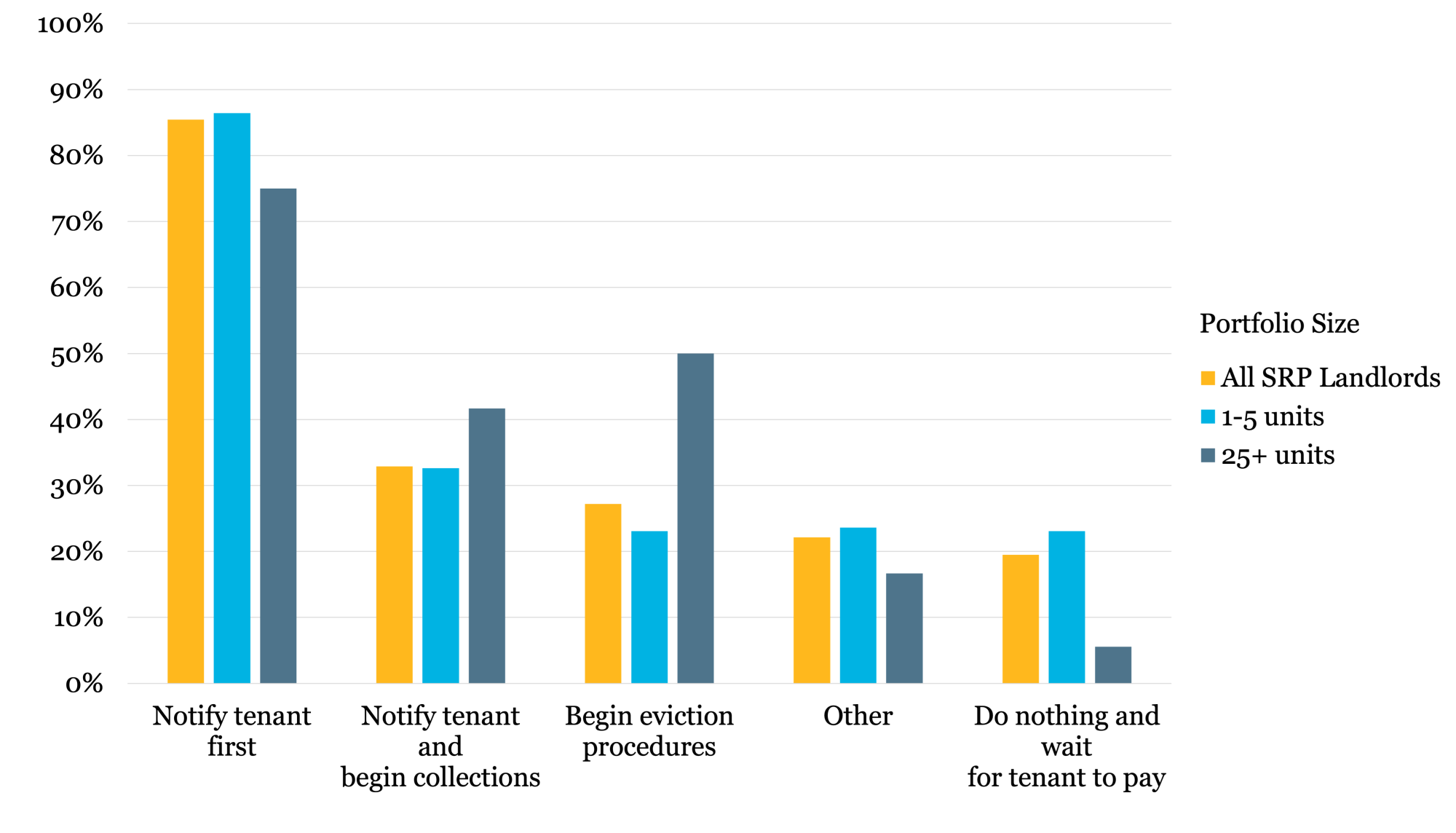

Figure 1. Responses of Small Rental Property Owners to Late Rent Payments, Based on Portfolio Size

Data: 2019 Survey

This was driven, in part, by the relatively hands-off approach of the typical owners of small rental properties—owners with only one or two units. The 2019 survey showed that smaller-scale owners were more likely to “do nothing and wait for tenants to pay.” Larger-scale owners were more likely to take action, including filing for eviction. A majority of owners with 25 or more units responded to a missed rent payment by beginning eviction procedures, about double the rate as the owners who had only one or two units.

What changed because of the pandemic?

In the survey we fielded in the spring of 2021, nearly one of three owners reported declines in rent revenue, although shares were higher for larger-scale owners. More than half of owners with more than 25 units reported income declines. The pandemic created a very different set of circumstances for owners facing a missed rent payment. The unprecedented rise in unemployment—concentrated among the jobs that the tenants of small rentals were disproportionately likely to have—made missed rent payments during the pandemic different in the eyes of owners. In interviews conducted before the pandemic, owners often attributed missed rent payments to their tenants’ poor financial planning. During the pandemic, for the most part, owners attributed missed rent payments to the tenant’s inability to pay rent. 71 percent of owners with missed rent payments reported that the missed payment was because their tenants did “not have sufficient money to pay rent” as opposed to having “sufficient money, but choosing not to pay rent.” The legal environment also changed, with eviction moratoria enacted at the state and federal levels that removed the option for owners to evict their tenants in most circumstances.

Not only did rent delinquencies become more common during the pandemic, they also became deeper. 18 percent of owners reported a missed rent payment at a given property in 2019. By early 2021, 26 percent of owners reported a missed rent payment due to the pandemic. The median depth of delinquency also increased from two months to three months behind on rent. Prior to the pandemic, only about a quarter of owners with a missed rent payment reported that this caused a “moderate” or “serious” cash flow problem with the property. During the pandemic over half of owners reported a moderate or serious cash flow problem.

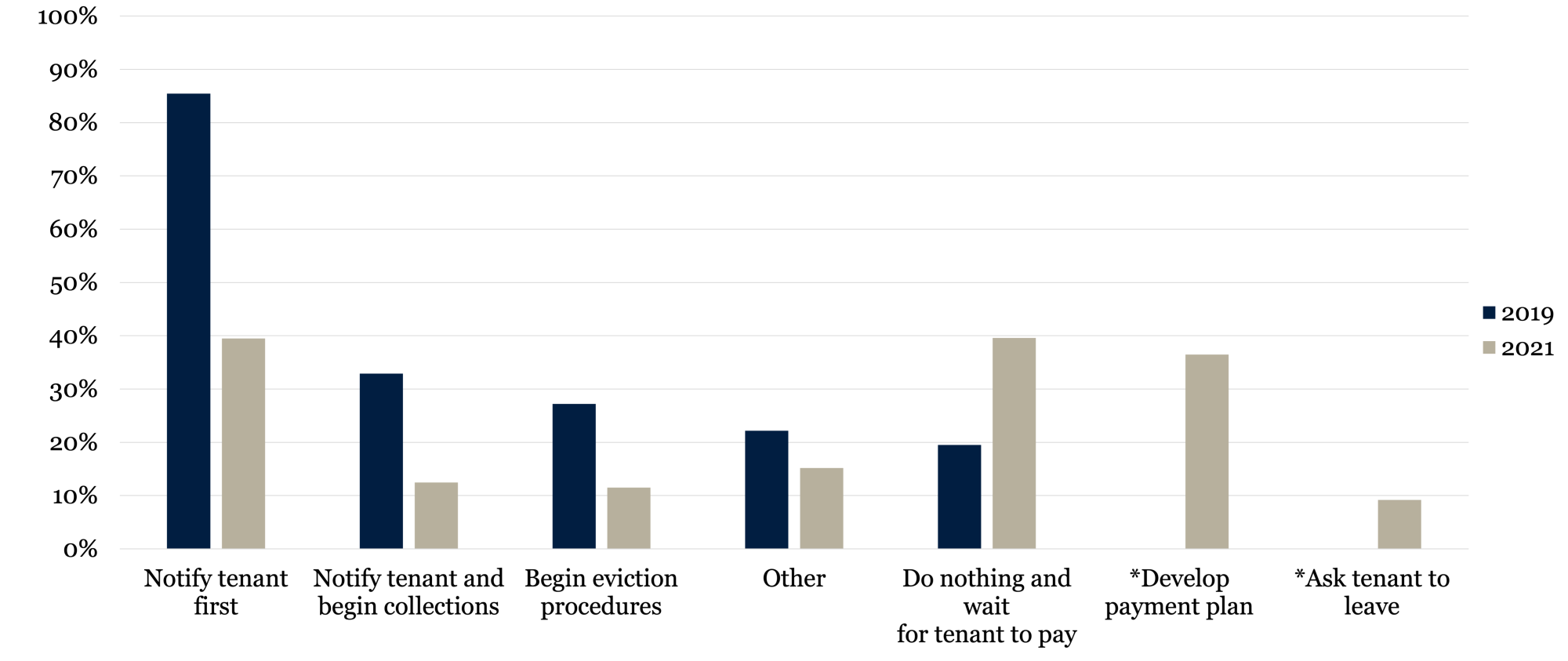

Despite these financial stresses, the on-the ground economic reality of the pandemic, along with the changed policy environment, led owners to relax their responses to missed rent payments. Owners were more likely to do nothing and wait, and also to develop payment plans for their tenants. They were less likely to begin collection procedures and file for eviction (though about 10 percent of owners did take these actions). As before the pandemic, smaller-scale owners were more likely to “do nothing and wait” compared to landlords who owned 25 or more units.

Figure 2. Responses of Owners of Small Rental Properties to Missed Rent Payments, By Year

Data: 2019 and 2021 Surveys

*These answer choices were not provided in the 2019 survey.

Public Policy & Landlords of Small Rental Properties

We estimate that about 4.5 million households in small rental properties missed a rent payment in 2019—mostly tenants with low incomes who did not have sufficient money to make rent in a given month. Usually these missed payments were resolved without an eviction, as landlords worked with the tenants in various ways. In large part it has fallen to these smaller-scale landlords to resolve what is ultimately a larger structural problem of the insufficient income of tenants. Outside of this private negotiation the only legal option available to landlords was eviction. Even as the pandemic saw landlords continue to work with struggling tenants in myriad ways, policy responses to the crisis changed the conventional dynamic by: (1) largely removing the ability to evict tenants experiencing income losses because of the pandemic, and (2) providing resources to address insufficient tenant incomes.

Smaller-scale landlords, with few exceptions, are not members of the national trade groups that fought to end the eviction moratorium. But interviews during the pandemic showed that many smaller-scale owners, particularly those with tenants in deep arrears, were frustrated by the moratorium. Many saw it as a de facto cancellation of rent. Some owners reported that the pandemic had caused serious financial strain, to the extent that they took steps to sell their properties to cover their costs. Some reported getting in touch with local elected representatives, but most reported that they had no idea who to contact.

Emergency rental assistance, as it became available, provided a direct means to address the root problem: income declines among tenants. However, the initial design and rollout of these programs has not been without its challenges for small-scale landlords. Owners reported that pandemic assistance programs appeared to be designed to assist professional landlords, not smaller-scale, less professionalized owners. Some owners cited the Paycheck Protection Program as one example. Unlike corporate owners, landlords of small rental properties often do not have salaried employees, so the program was not applicable to the expenses or lost income of the providers of about half the nation’s rental units. Emergency rental assistance programs also appear to be tapped at higher rates by more professional owners. Many small-scale owners, even those in financial stress, were unaware of rental assistance at the time that the survey was conducted even though $25 billion had already been appropriated by Congress and some state and local programs had been operating for months.

Improving the design and deployment of assistance to better reach smaller-scale landlords during the ongoing crisis would not only help avoid a spike in evictions now that protections have begun rolling back. It could also lay the groundwork for longer-term changes that ensure the U.S. does not just revert to the problematic pre-pandemic system in which eviction is almost always the only option provided by the state to deal with rent non-payment. It is possible that landlords’ increased use of repayment plans and other methods to get tenants current will lead them to take these steps even as the impact of pandemic subsides. But beyond the pandemic, the larger-scale problem of the mismatch between renter incomes and the cost of providing housing needs a better solution than relying on the flexibility of smaller scale landlords and the eviction system.

Substantially increasing the number of Housing Choice Vouchers is one means to address the chronic problem of affordability. Two recent briefs show that the voucher program and other rent subsidies have reduced renter debts and stabilized landlord revenue during the pandemic. Emergency Rental Assistance provides another model. Creating a permanent program that is available to tenants and landlords to cover brief rent shortfalls could provide a means to address the needs of the millions of renters who, while typically have incomes that allow them to make rent, live paycheck-to-paycheck and occasionally fall behind. The program could be less costly and burdensome than eviction to landlords, while providing the public sector with a means to stem evictions at a lower cost relative to vouchers. Such a program would need to address the well-documented shortcomings of the early rollout of ERA and deal with a new set of concerns (e.g. guarding against fraud and ensuring that the program addressed only cases of financial hardship). But the lessons learned from the hundreds of ERA programs currently in operation provide a wealth of information on how to make such a program work. In addition to stabilizing tenants and landlords, a permanent program could also be at the ready in emergencies like a pandemic, natural disasters, or other unexpected large-scale shocks that cause sudden declines in renters’ incomes. But in normal times, funded at lower levels, they could help deal with the long crisis of rental affordability in the U.S.