Small Houses, Big Impact: Accessory Dwelling Units in Underutilized Neighborhoods

Published On August 3, 2016

As NIMBY’s (Not in My Backyard) continue to oppose new housing development, a new group of homeowners are saying yes, by literally building new homes in their own backyards. Accessory dwelling units (ADUs), also referred to as in-law suites or granny flats, are smaller, independent units on the same lot as a single family home (sometimes even an extension or a reworking of the home itself). ADUs were common in the early twentieth century, but went out of favor post-World War II as single-family, suburban style development characterized by large lots and an emphasis on the nuclear family became the norm.

Now, ADUs are re-emerging, this time as a way to increase the supply of housing, particularly in high-cost cities experiencing rapid growth in demand. ADUs have many advantages. They are cheaper to build than a classic single-family home, allow for flexible living arrangements for families, and can serve as a source of financial stability to homeowners, including and especially seniors living on fixed incomes. But zoning, excessive fees, and other regulatory barriers often limit a homeowner’s ability to build an ADU. Those who oppose ADUs want to see those barriers preserved, while those who support ADUs are working to bring them down.

What drives opposition to ADUs? Some neighbors and members of city government are concerned that the expansion of ADUs will put undue strain on city services and infrastructure, like parking, water and sewer, and electricity. In addition, opponents worry that the increased density will destroy the “character” of their suburban neighborhoods.

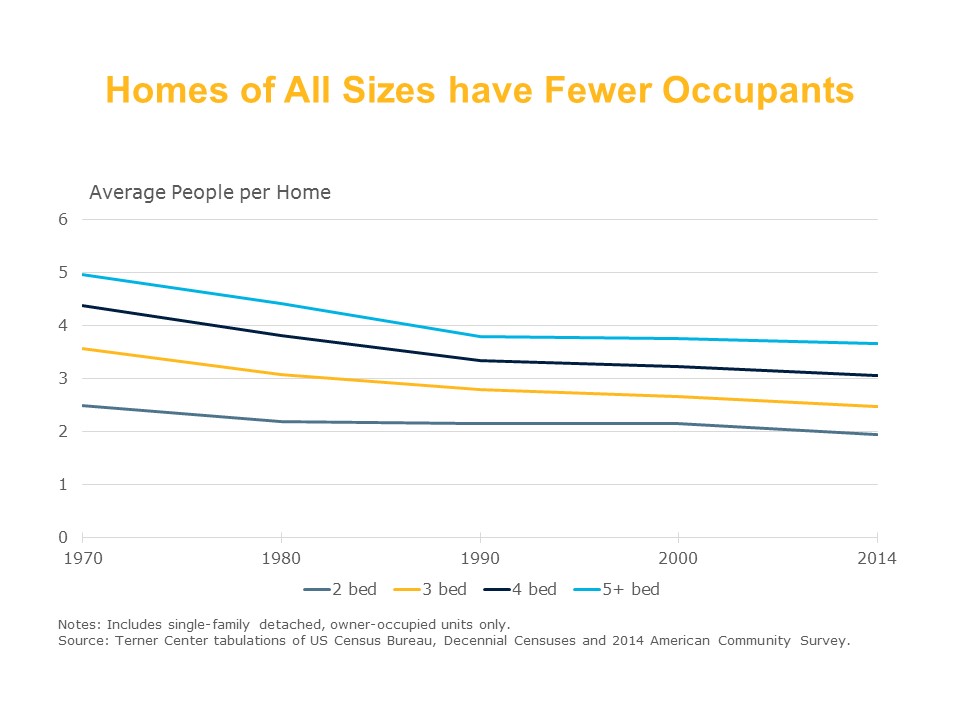

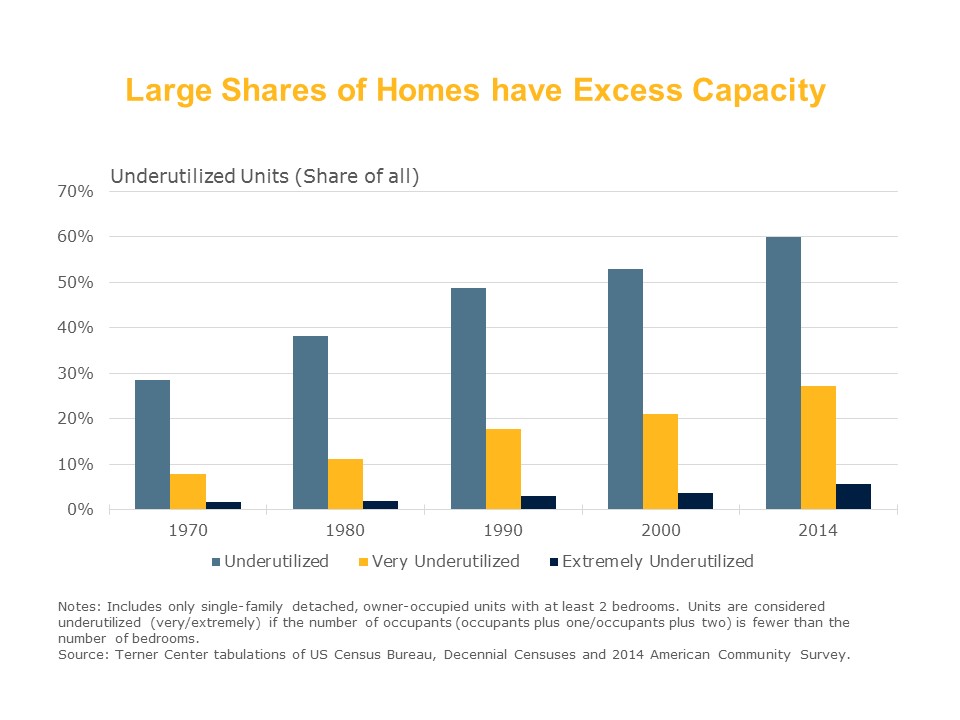

But, in fact, suburban homes and neighborhoods are a whole lot emptier than they were forty years ago, meaning that there’s plenty of “room to grow” before municipal services and neighborhood character will be meaningfully affected by increases in density. Single family homes are housing smaller families in larger homes and lots than ever before. To determine exactly how many single-family homes are “underutilized,” the Terner Center analyzed census data from the past forty years on changes in family size and the number of bedrooms we’re living in.

What we found was striking. Since 1970, the number of people per bedroom has steadily declined.

Even in households where families use an additional room as a guest room or office, there are still 16.4 million homes across the country with surplus bedrooms in addition to one reserved for miscellaneous use.

Easing the barriers to construction of ADUs will help make better use of underutilized land in these communities, and ease some of the pressures they are experiencing. Many cities in Northern California (Berkeley, Oakland, and Redwood City, for example), along with others nationwide (including Portland, OR, Honolulu, HI,and Cambridge, MA) have already loosened restrictions on ADUs, and others are considering similar rule changes. California and Massachusetts are both considering new legislation that would loosen restrictions statewide, and New Hampshire recently passed a similar law that will go into effect June of 2017. These policies have the potential to increase the supply of housing, as well as create positive fiscal and economic stimulus to local economies.

We can now more clearly see how much space many of our neighborhoods aren’t using. As UC Berkeley Professor Karen Chapple, who has done extensive work on ADUs notes, “This research underscores the real opportunity ADUs present. Homeowners are eager to build them, and reducing current barriers to ADU construction will help to make better use of all the underutilized space in our neighborhoods. Ultimately, ADUs are one important, cost-effective solution to easing the ever-growing housing pressures in high cost cities.”

Data and methods:

The data in this post are based on the Public Use Microdata Samples (PUMS) from the 1970-2000 decennial Censuses and the 2014 one-year American Community Survey. The data were obtained from the IPUMS-USA database, maintained by the Minnesota Population Center at the University of Minnesota (www.ipums.org).

The universe of units for this analysis excludes group quarters and is limited to owner-occupied, detached single-family homes with at least two bedrooms. Zero and one-bedroom homes were excluded as they are atypical among single family homes and represent a small share of all single-family detached, owner-occupied units. Group quarters follows the 1970 definition (more than 4 household members unrelated to the household head are identified as group quarters) for consistency across sample years. From 1970-2008, the number of bedrooms is top-coded at 5, meaning that units with more than 5 bedrooms were assigned a value of 5. For consistency, 2014 units with more than 5 bedrooms were also assigned a value of 5.

The analysis of housing unit utilization compares household size with the number of bedrooms in a unit. Underutilized homes have fewer people than the number of bedrooms. Very underutilized units allow for one extra bedroom, so have at least 2 more bedrooms than the number of occupants. Extremely underutilized units have at least 3 more bedrooms than the number of occupants.