Potential Impact of SB 478 on Local FAR and Minimum Lot Size Requirements

Published On April 5, 2021

In recent years, the California legislature has found some success in facilitating the development of small-scale housing, particularly accessory dwelling units (ADUs), even as legislation focused on encouraging larger-scale development has faltered. The result has been a significant increase in the uptake of ADUs across the state. To build upon these gains, the 2021 legislature is looking to build upon the progress made in facilitating smaller, less controversial housing development. Senate Bill 478 by Senator Scott Wiener of San Francisco is one piece of these efforts. This bill, known as the Housing Opportunity Act, aims to ensure that overly restrictive land use requirements do not stymie the production of small-scale development where it would otherwise be legal based on zoned density. This is an important topic because of the increasing prominence of various bills introduced at the state level that would compel or encourage localities to zone for “missing middle” housing, which refers to lower-density housing of 10 or fewer units. SB 478 proposes two specific statewide policy changes: establishing a minimum floor area ratio (FAR) that cities could impose on all land zoned for two to ten residential units, and establishing minimum lot sizes for parcels that are 2-4 units and for parcels that are 5-10 units.

Could the changes proposed in SB 478 catalyze more missing middle housing? And how many cities would be impacted by these reforms? This analysis examines the extent to which policies such as those set forward in SB 478 may be impactful by examining FAR and minimum lot size requirements statewide. To do this, we utilized our 2019 Terner Center California Residential Land Use Survey (TCRLUS). The survey, conducted in 2017 and 2018, includes responses from 252 cities and 19 unincorporated county areas in the state, and includes insights on a range of questions on local zoning, development approval processes, affordable housing policies, and rental regulations.1

In addition to the TCRLUS, we also examined literature on the impacts of restrictive land use requirements, including FAR and minimum lot sizes.

Background

Literature shows that restrictive land use requirements—such as low FARs and high minimum lot sizes—limit new housing development and correlate with other negative housing outcomes. A 2019 study of zoning laws and housing conditions in California cities found that the share of land zoned for single-family housing and more restrictive minimum lot size requirements predicted higher housing costs (measured in terms of median gross rents and median home values) compared to other jurisdictions in the same metropolitan area. Municipalities that enforce low-density zoning through stringent minimum lot size requirements were less likely to be home to Black and Latinx communities and blue-collar workers.2 Research from the Mercatus Center used data from the TCRLUS (which includes minimum lot size and FAR requirements) to measure regulatory stringency in housing development, and found that more regulation is associated with slower housing growth. High regulatory stringency and slower housing growth were even more strongly and significantly correlated when the supply growth was adjusted for existing density and growth in demand.3 Large minimum lot sizes have been shown to have a positive, statistically significant effect on housing prices.4 These requirements also raise the cost of construction and thus cause a decline in the supply of housing.5 A study of Bay Area municipalities demonstrated that establishing large minimum lot size requirements increased the cost of housing, with these additional costs being borne by citizens.6 FAR has also been linked to housing costs. As these requirements limit the height of buildings, restrictions on FAR have been theorized to cause cities to expand outwards to accommodate new residents. This increases both the price of housing and average commute time for residents of cities with such restrictions.7

SB 478

SB 478 sets minimum standards for both FAR and minimum lot size requirements for residential areas zoned for between two and ten units. FAR is defined as the ratio of a building’s total floor area in relation to the size of the lot the building sits on. For example, if a lot is 5,000 square feet in size, and the building on that lot is 2,500 square feet (total for all floors) in size, the FAR is .5. Put another way, if a city has a FAR of .25, then a 10,000 square foot lot is allowed to have a building as large as 2,500 square feet in total, including the square footage of every floor of the building. Minimum lot size is defined as the minimum size of a lot allowed for constructing a specific dwelling type. For example, a minimum lot size of 5,000 square feet for single-family homes means that a single-family home can’t legally be constructed on any lot smaller than 5,000 square feet.

As currently drafted, SB 478 would restrict the FAR and minimum lot size standards that a city could impose on certain parcels. For FAR, the bill prohibits a city from imposing a residential FAR lower than 1.5 for any parcel zoned for two to ten units. SB 478 would also create a new minimum lot size standard for parcels zoned for between two and four units as well as a separate standard for parcels zoned for between five and ten units. These standards have yet to be determined in the legislation and may be included in the bill at a later date.

Findings

While most cities do not use FAR to control building size for residential development, the 1.5 FAR standard in SB 478 would exceed the current residential multifamily FAR in 85% of localities.

In our survey sample of over 250 cities and counties, only 53 reported FAR standards for multifamily development. This is most likely because these jurisdictions use other methods to dictate the size of buildings that are built in residential areas, such as setbacks, height, and density. However, the 1.5 FAR standard proposed in SB 478 would be potentially very significant in the majority of cities that do use FAR as a residential development standard, based on the responses we received in the TCRLUS.

In cities that do impose a FAR for multifamily residential, a strong majority would be impacted by the proposed 1.5 FAR standard (Table 1). Nearly 70% of respondents reported an FAR between .26 and 1, with only seven localities reporting FARs between 1.01 and 1.5. Just eight localities reported having an FAR above 1.5, the minimum threshold in SB 478. Single-family FAR utilization was slightly higher, with 77 respondents reporting use of FAR on this housing type (Table 2). Of these jurisdictions, 71.4 percent of localities reported single-family FARs between .26 and .5.

Table 1. TCRLUS: Multifamily FAR Requirements

| Maximum FAR | # of Municipalities | % of Municipalities |

| 0.25 or lower | 1 | 1.9% |

| 0.26 to 0.5 | 18 | 34.0% |

| 0.51 to 1 | 19 | 35.8% |

| 1.01 to 1.5 | 7 | 13.2% |

| Higher than 1.5 | 8 | 15.1% |

N=53

Table 2. TCRLUS: Single-Family FAR Requirements

| Maximum FAR | # of Municipalities | % of Municipalities |

| 0.25 or lower | 3 | 3.9% |

| 0.26 to 0.5 | 55 | 71.4% |

| 0.51 to 1 | 17 | 22.1% |

| 1.01 to 1.5 | 2 | 2.6% |

| Higher than 1.5 | 0 | 0.0% |

N=77

A strong majority of cities require minimum lot sizes greater than 2,500 square feet for both single-family and multifamily projects.

As opposed to FAR, minimum lot sizes are common standards used for residential development, and a majority of localities set their standards higher than 2,500 square feet.

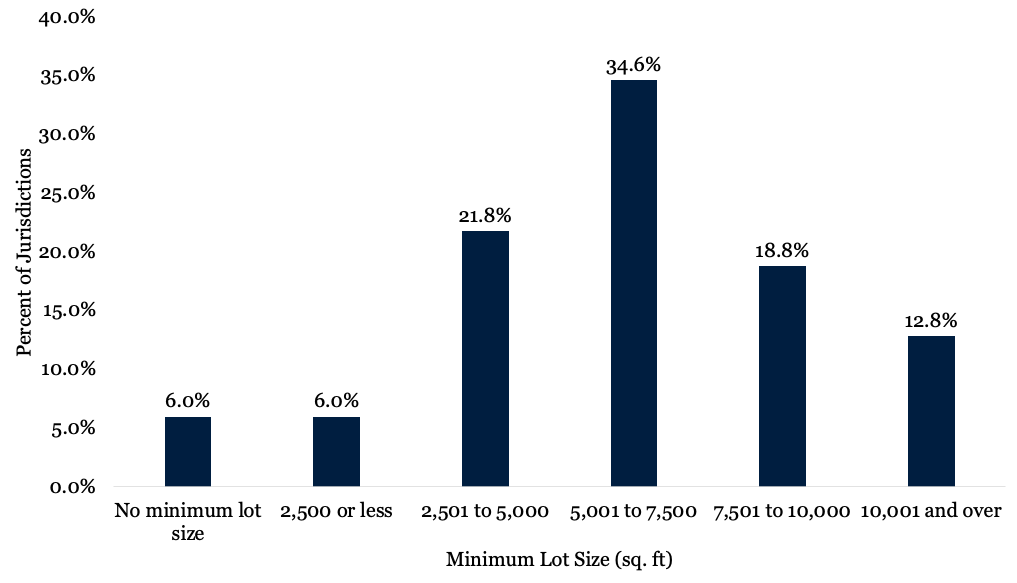

Only 28 jurisdictions in the TCRLUS reported having either no minimum lot size or a minimum lot size of 2,500 square feet or less for multifamily parcels. 75.2% of jurisdictions reported requiring a minimum lot size between 2,501 and 10,000 square feet. 12.8% reported requiring more than 10,000 square feet (Figure 1).

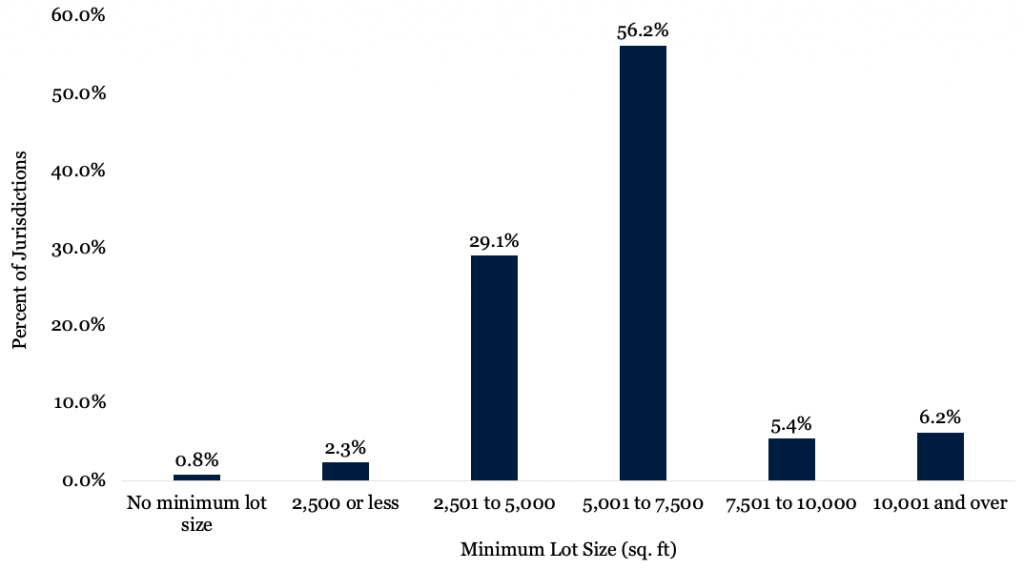

Reported minimum lot sizes were similar for single-family homes, with only eight jurisdictions either allowing single-family homes on lots smaller than 2,500 square feet or lacking minimum lot size requirements for single-family homes (Figure 2). A majority (56%) require between 5,001 and 7,500 square feet. Six percent require greater than 10,000 square feet. For example, the city of Atherton reported a minimum lot size of 43,560 square feet—exactly one whole acre—for the construction of a new home.

Figure 1. Multifamily Minimum Lot Size Across California Jurisdictions Figure 2. Single-Family Minimum Lot Size Across California Jurisdictions

Figure 2. Single-Family Minimum Lot Size Across California Jurisdictions

Conclusion

The provisions proposed in SB 478 would significantly alter the FAR and minimum lot size requirements that most California jurisdictions impose on new, small-scale residential development. This could have important implications for the creation of “missing middle” housing by allowing more flexibility in the size and shape of new small-scale development, as well as expanding where in a city such housing could be built. However, it should also be noted that jurisdictions do not rely on FAR and minimum lot size alone to limit the size and type of new residential development. Requirements dictating setbacks, height, density, roof pitch, and parking, to name a few, all impact new housing feasibility, particularly for smaller-scale development. While SB 478 will limit some restrictive land use requirements, these other restrictions may continue to limit what may be built and there is a possibility that some cities may tighten these restrictions in order to offset reforms at the state level.

Endnotes

- While the TCRLUS provides us with a broad view into local planning practices, it does not necessarily reflect the full breadth of housing regulations in any one jurisdiction. Specifically, tThe TCRLUS captured information on just two types of housing: single-family, and multifamily. Many jurisdictions may have different FAR and lot size requirements for different types of multifamily zones (e.g., minimum lot size for parcels zoned for 10 units may differ greatly from lots zoned for 100 units) or varying requirements based on geographic variation. As a result, our survey responses may not fully reflect existing requirements for “missing middle” housing typologies in all localities.

- Rothwell, J. (2019). Land Use Politics, Housing Costs, and Segregation in California Cities. Terner Center for Housing Innovation Land Use Working Papers. Retrieved from: http://californialanduse.org/download/Land%20Use%20Politics%20Rothwell.pdf.

- Furth, S., & Gonzalez, O. (2019). California Zoning: Housing Construction and a New Ranking of Local Land Use Regulation. Mercatus Center: George Mason University. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3463421.

- Cho, M., & Linneman, P. (1993). Interjurisdictional Spillover Effects of Land Use Regulations. Journal of Housing Research, 4(1), 131–163. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24832756.

- Pogodzinski, J. M., & Sass, T. R. (1991). Measuring the Effects of Municipal Zoning Regulations: A Survey. Urban Studies, 28(4), 597–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420989120080681.

- Rosen, K. T., & Katz, L. F. (1981). Growth Management and Land use Controls: The San Francisco Bay Area Experience. Real Estate Economics, 9(4), 321–344. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-6229.00247.

- Bertaud, A., & Brueckner, J. K. (2005). Analyzing building-height restrictions: predicted impacts and welfare costs. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 35(2), 109–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2004.02.004.