Sacramento Leapfrogs

State Capitol

in Zoning Reform Race

Published On January 28, 2021

Over the last few years, the California state capitol has seen several efforts to override local restrictions that prevent the construction of multiple housing units in neighborhoods zoned solely for single-family housing, to little or no avail. And while legislators will again take up major housing reform in 2021, the city that hosts our state capitol—Sacramento—is taking matters into its own hands. Last week, the Sacramento City Council unanimously approved a preliminary plan to allow for up to four units to be built on nearly every residential parcel throughout the city. The move pushes America’s Farm to Fork Capital into the ranks of major American cities such as Portland and Minneapolis that have taken steps to address the racist legacy of exclusionary zoning through progressive land use reforms. The move is more than symbolic: Sacramento faces significant rent burden pressures, especially as more San Francisco Bay Area residents priced out of the Bay Area migrate in. With this vote, Sacramento city leadership is affirming their commitment to catalyze the construction of enough and more diverse housing to accommodate all who would like to reside in their city.

Achieving major land use reform at the local level is not easy, as documented in our 2019 paper on lessons from places that have successfully tackled land use reform But changes that enable denser housing to be built are critical to meeting a city and region’s diverse housing needs. The Sacramento proposal, which still must go through the city’s 2040 general plan update, followed by a zoning update, matches or exceeds several other efforts around the country. The plan would allow up to four units to be built by-right (i.e., projects cannot be denied a permit if they comply with codified design and building requirements) in any part of the city. Just as important, city planners have proposed to eliminate critical design barriers: parking requirements would be abolished and restrictive setbacks or floor area ratios would be eliminated, thus enabling builders to utilize more of each lot. These important provisions would greatly increase the likelihood that duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes would actually be built.

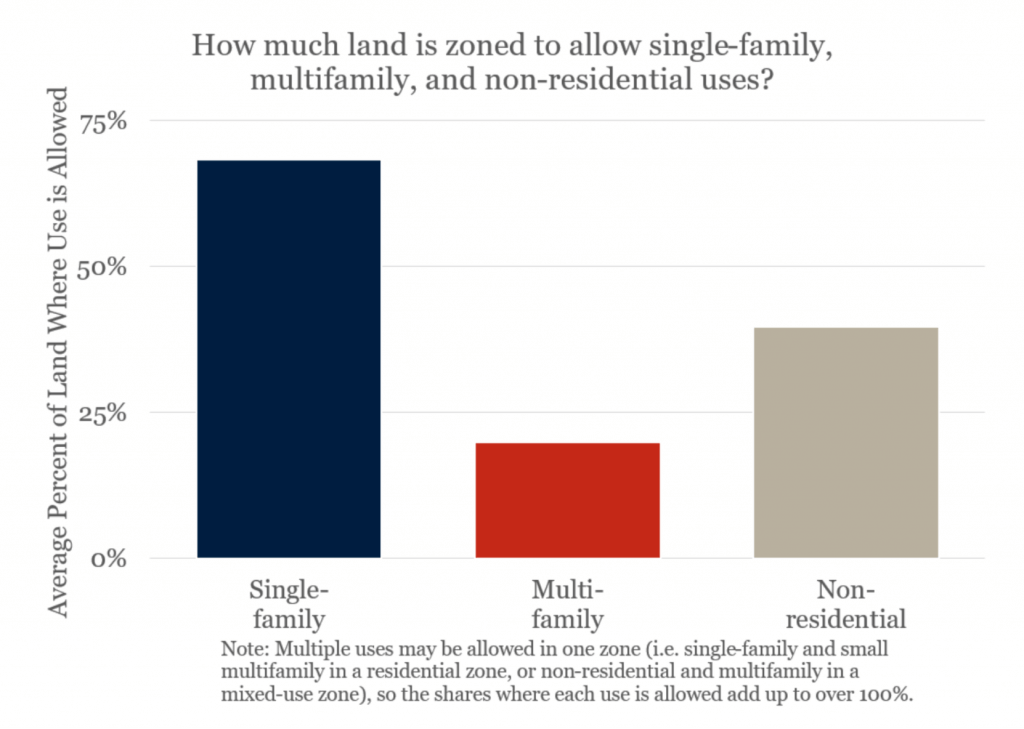

The policies proposed by Sacramento would be unprecedented for any major city in California. As our work has shown, a majority of the state’s zoned land allows single-family residential, with far less land dedicated to multifamily. In Sacramento, planners estimated that 70% of Sacramento’s residential neighborhoods—comprising 43% of the city’s total land area— are zoned for single-family only.

Figure 1: Land Zoned for Residential and Non-Residential Uses, Terner Center Residential Land Use Survey

Our work has also found that the prevalence of single-family housing has had significant consequences for equitable housing outcomes. On the homeownership side, zoning restrictions limit what can be built, and as a result, new ownership housing production increasingly has shifted toward larger-format and single-family homes affordable only to more affluent households. Increasing production and diversifying the types of housing built could provide more ownership opportunities for lower-income and younger homebuyers given that multi-family, attached, and small single-family homes house a larger share of younger and lower-income homeowners than average. On the renter side, the lack of rental opportunities in neighborhoods dominated by single-family housing limits the ability of lower- and moderate-income renters to access those neighborhoods. Relative to other neighborhood types, single-family tracts have the lowest poverty rates, highest median incomes, and greatest share of households with a bachelor’s degree or higher, but fewer and more expensive rentals.

To those closely watching, it should come as no surprise that Sacramento is demonstrating such leadership on zoning reform, as policymakers there have demonstrated willingness to undertake progressive housing reforms in the past. Specifically, our work has identified Sacramento as a leader in development fee best practices, creating consistent rules and guidelines for fee implementation and paving the way for fees that are lower and more predictable. The city also offers a fee estimation service, which will be especially useful for smaller builders who will eventually take advantage of the new fourplex provisions. And the city has been in the forefront of unwinding discretionary review with its recent enactment of by-right zoning in its downtown, giving residential developers greater certainty—and important reform of onerous project-level environmental reviews—as they seek approval from city planning staff for proposed projects.

Sacramento should be commended for their leadership on zoning reform as state leaders continue to develop statewide solutions. To be sure, California has had some success with single-family zoning reform, most notably with legislation allowing for Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs) to be built on most single-family-zoned parcels. However, given that financing can be out of reach for many lower-income homeowners and the units typically cannot be built for-sale, ADUs are only one part of a broader housing solution. While sweeping efforts to legalize multifamily housing on single-family zoned parcels statewide have fallen short in recent years, 2021 could finally see the passage of a major zoning overhaul. Specifically, Senate Bill 1120 (Atkins), a 2020 bill that would have allowed for up to four units on nearly six million existing single-family parcels, has been reintroduced this year as Senate Bill 9 (Atkins).The prospects for SB 9 are optimistic given that its predecessor managed to pass both legislative chambers last year, failing victim only to a lack of time.

Regardless of state level land use regulations, Sacramento may be prescient in their actions. With forthcoming sixth-cycle Regional Housing Needs Assessment (RHNA) already underway, Sacramento is facing an obligation from the state to increase the number of new homes that can be built on its residentially zoned lands by 89%. Incorporating these upzonings as part of the state RHNA process will make it exceedingly difficult for future Sacramento city councils to reverse. Particularly given new, much harsher sanctions for cities that fail to meet their RHNA goals, cities should already be thinking about the best ways to accommodate significant numbers of new homes, and reconsidering the sanctity of single-family zoning may offer one key solution, in addition to others, such as repurposing commercial sites.

To that end, statewide legislative efforts to address the housing crisis must also include solutions that facilitate faster local adoption of progressive zoning reforms that untether local planning departments from the usual barriers to implementing rezonings, such as lengthy and expensive environmental reviews (which are not required for downzonings, ironically enough). Some bills have already been introduced to accomplish this goal, such as Senate Bill 10 (Wiener), and other ideas should be reconsidered as well, such as last year’s stalled Assembly Bill 3155 (Rivas and Quirk-Silva).

We hope that Sacramento will ultimately follow through with these new, dynamic policies, especially in the face of mounting price pressures in the region. If successful, Sacramento can serve as a model for other cities, both in California and beyond.