California Needs to Build More Apartments

Published On July 11, 2019

By Jenny Schuetz, PhD, the Brookings Institution, Metropolitan Policy Program and Cecile Murray, MSCAPP, University of Chicago

This paper is part of a working paper series that utilizes the Terner Center California Residential Land Use Survey to assess the implications of California’s state and local policies for housing. Read the full paper here.

So much ink has been spilled over California’s persistently high housing costs that it has become a cliché. Nearly everyone agrees that high costs are a substantial problem – not just for families struggling to pay rent, but also for companies trying to attract and retain workers, and for the state’s economic future. But not everyone agrees on how to solve the problem. Residents and activists are increasingly sorting into opposing camps around their preferred solutions: expand rent control, shed jobs, or build more housing.

Our new report—part of a working paper series from the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at the University of California at Berkeley—comes down firmly in the “build more housing” camp. Using new data from the Terner Center California Residential Land Use Survey on local land use regulations across California, we examine how cities use zoning to deter development of new multifamily buildings. Too many of California’s high-rent cities have built too few apartments, contributing to the current shortage.

California’s apartment market is upside down, economically speaking.

A fundamental precept of economics is that, when the price of one production component increases, firms will use less of the expensive input to produce their goods. For instance, when wages for cashiers increase, supermarkets will install more self-checkout machines and hire fewer cashiers. In housing markets, as the value of land increases, developers will use less land per new housing unit, building homes on smaller lots or stacking homes vertically in apartment buildings. If housing markets are functioning well, we would expect to see more new apartments constructed in communities with high initial rents. But because many affluent communities are hostile to apartments, they often adopt zoning and related policies intended to limit development of multifamily buildings.

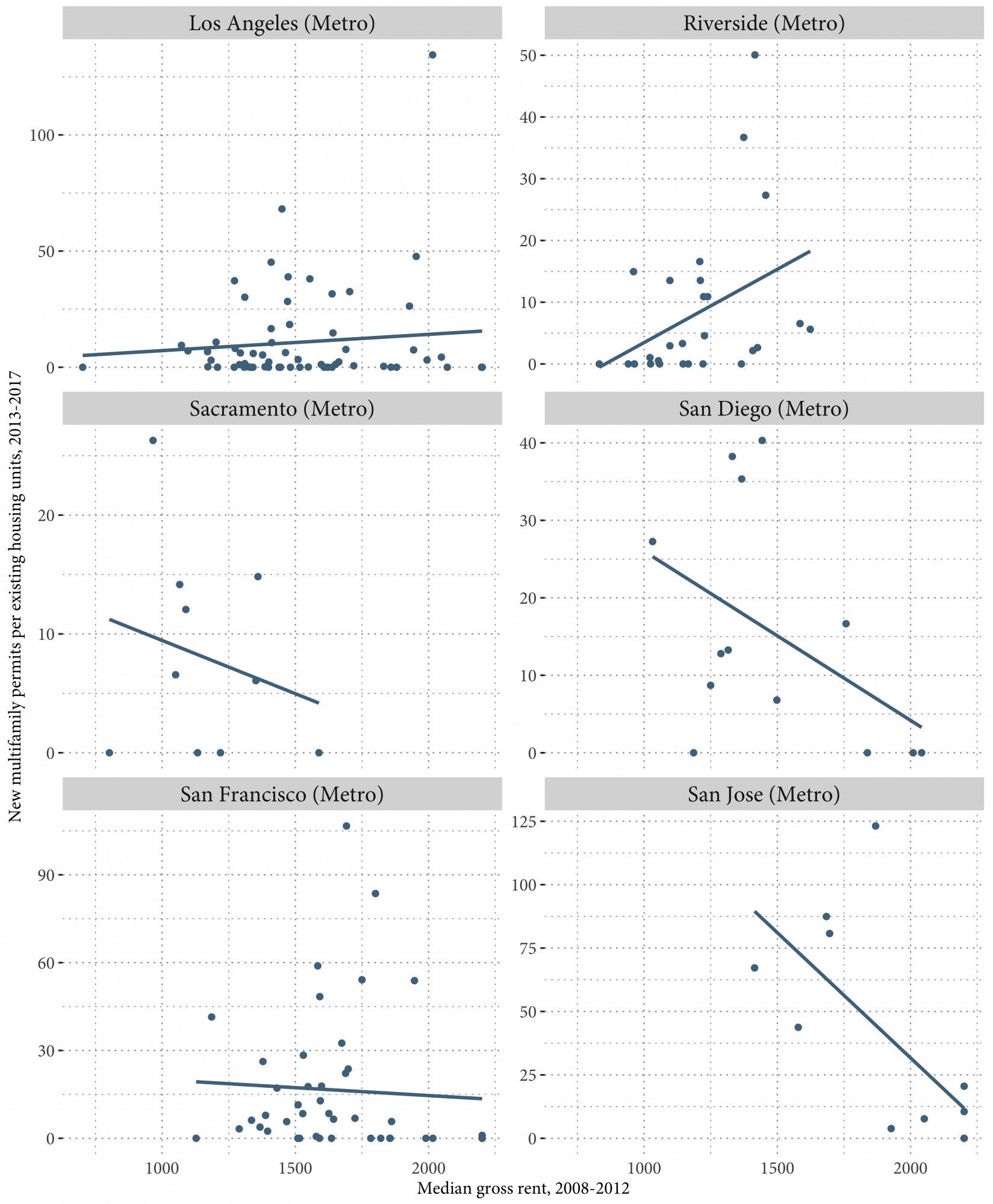

Across much of California, apartment markets are working in the opposite way that economists expect: communities with high rents build fewer new apartments than lower-rent communities within the same metropolitan area (Figure 1). Of the six largest metropolitan areas, only Los Angeles and Riverside had a positive relationship between rents in 2010 and the number of new apartments built from 2013 to 2017. In the remaining four metros – including San Francisco and San Jose, the epicenters of exploding housing costs – high-rent communities built fewer new apartments than their cheaper neighbors. This pattern strongly suggests that zoning or other institutional factors are constraining development.

Figure 1: California’s expensive cities aren’t building their fair share of apartments

City-level new multifamily permits versus median rents, by metro area

Source: Each dot represents a city within the metropolitan area. Rent from 2008-2012 American Community Survey. Permits from Census Bureau’s new residential construction series.

Apartments, how do we loathe thee? Let us count the ways.

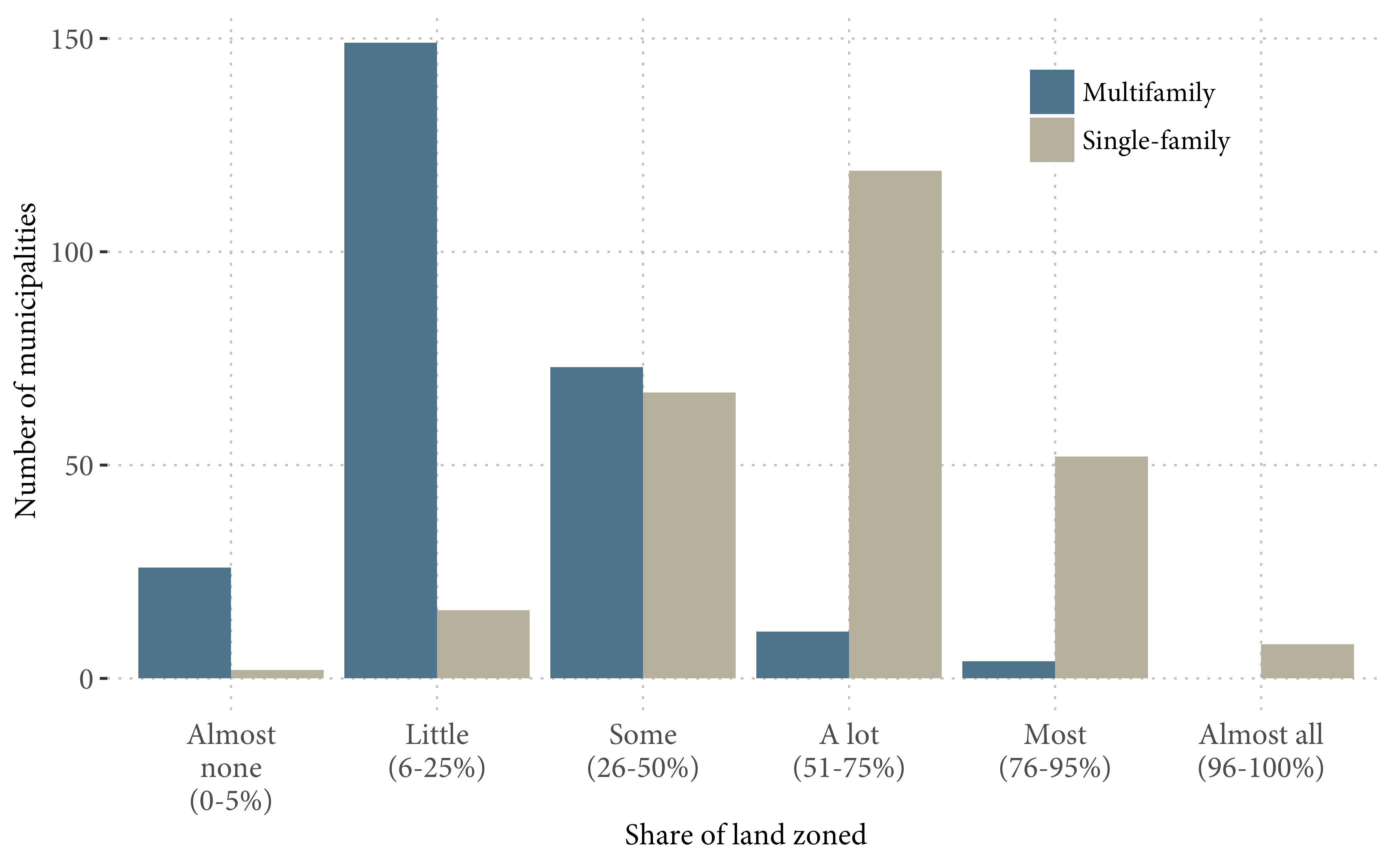

One difficulty of advocating for apartment-friendly zoning reforms is that local governments have many different tools to discourage unwanted development. Many communities simply ban multifamily buildings outright on most of their land. Whereas the median California city allows single-family homes on at least 50 percent of land, the typical city allows apartment buildings on less than 25 percent of land (Figure 2). Even where apartments are allowed, local governments often restrict building heights or apartment densities to a degree that makes development financially infeasible.

Figure 2: Municipalities prohibit apartments on most land

Share of land zoned for multifamily and single-family homes

Source: Authors’ calculations using Terner Center Residential Land Use Survey.

Besides regulating physical characteristics of apartment buildings, most California jurisdictions rely on ad hoc, discretionary processes to permit development. That is, developers seeking to build apartments must request approval on a case-by-case basis from the local city council and/or zoning board, while holding public meetings at which existing residents can raise objections. This ad hoc approval process makes building new housing longer, risker, and more expensive for the developer, which translates into higher costs for the finished housing.

Cities with restrictive zoning have succeeded in their goal.

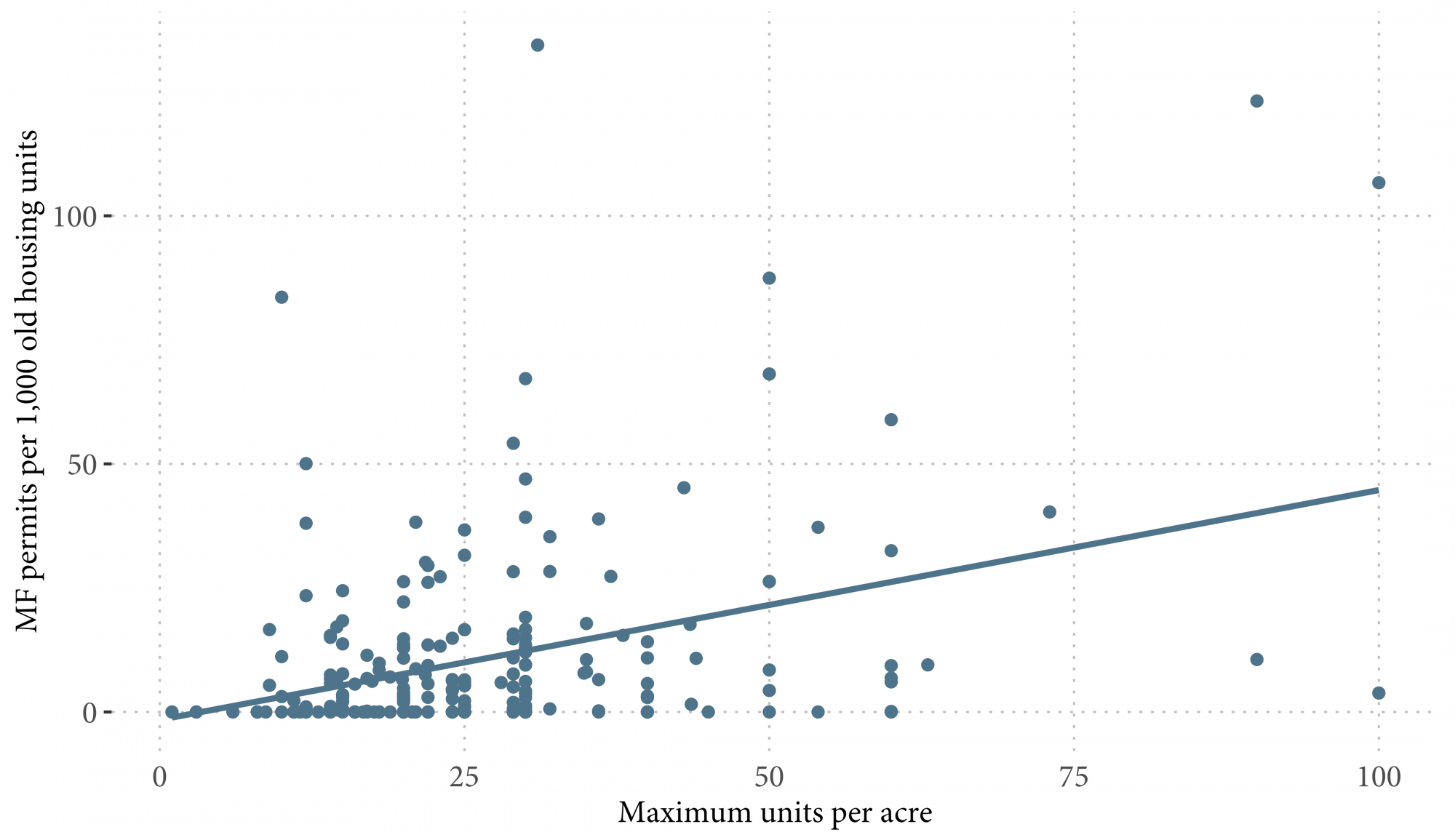

Communities whose residents are hostile towards apartments adopt restrictive zoning laws for a reason: they want to discourage or block development. Turns out, anti-apartment zoning works: cities that set lower allowable densities and building heights built fewer apartments (Figure 3). We find statistically significant relationships between new multifamily permits and two components of zoning: the number of apartments that can be built per acre of land, and maximum building height. Even controlling for demographic and economic characteristics, places with more restrictive zoning built fewer apartments.

Figure 3: Cities with low density zoning built few apartments.

City-level new multifamily permits versus maximum allowed units per acre

Source: Each dot represents one city. Units per acre from Terner Center Residential Land Use Survey. Multifamily permits from Census Bureau’s new residential construction series.

Breaking the housing logjam will require radical policies – and political courage.

The unwillingness of so many California cities to allow enough new housing, and housing that is affordable to a range of incomes, has finally pushed state policymakers to take action. In 2019, state legislators introduced several ambitious bills that would override some elements of local zoning – an important step in the right direction. However, these bills face significant political opposition.

Hostility to new development runs deep, and affluent communities have become highly adept at wielding the discretionary approval process to their benefit. Even if courts or the state legislature mandated that all cities allowed taller buildings and more units per acre, unless they must also make the development process less discretionary, it is likely that anti-development cities would continue to block apartments on a project-by-project basis.

If California policymakers want more apartments to be built, they should attach financial incentives directly to housing production, not merely to zoning revisions on paper. The state has some legal and financial tools it could use more aggressively. For instance, statewide funds that are dispersed to localities for transportation projects and schools could be made contingent on increased housing production. Although local governments are currently required to submit a housing plan to the state Department of Housing and Community Development, there have been few consequences for localities that fail to meet their plans.

Until residents of exclusionary communities face financial penalties for their resistance to development, they will not change their behavior. But increased state oversight of local land use will be politically unpopular, especially among affluent communities. California’s governor and states legislature will need strong spines to face down recalcitrant homeowners.