Housing Opportunities: Governor’s Reorganization Plan to Create the California Housing and Homelessness Agency

Published On June 2, 2025

Authors:

Doug Shoemaker, Terner Center Affiliate

Geeta Rao, Senior Director, Northern California Market, Enterprise Community Partners

Co-authors:

Sarah Karlinsky, Director of Research and Policy, Terner Center for Housing Innovation

Ben Metcalf, Managing Director, Terner Center for Housing Innovation

The Administration of California Governor Gavin Newsom recently put forth a Government Reorganization Plan (GRP) to divide the current Business, Consumer Services, and Housing (BCSH) Agency into two new agencies: the California Housing and Homelessness Agency (CHHA) and the Business and Consumer Services Agency.

This commentary:

1) Explains the problems that the GRP is trying to address; and

2) Assesses the GRP in the context of feedback from stakeholders and broader efforts to achieve housing reform.

What problems is the reorganization plan trying to solve?

In general terms, the GRP is one of the Administration’s responses to California’s interrelated housing affordability and homelessness crises. The six most expensive jurisdictions for housing in the country[1] are all located in California. California also has the nation’s largest unsheltered homeless population in both per capita and absolute terms.[2]

More specifically, the GRP is attempting to address the fact that the State’s affordable housing finance system is divided among multiple governmental entities, each headed by a separate director or executive director. This fragmentation is highly unusual among states and is broadly viewed as undermining the State’s ability to efficiently deliver affordable housing in California. In most states, housing finance functions are consolidated into one or two agencies.

The Terner Center’s recently released brief, “Reducing the Complexity in California’s Affordable Housing Finance System,”[3] quantifies the cost of requiring affordable housing developers to stitch together many different sources of funding to make projects pencil.

In analyzing data for new construction projects awarded LIHTC subsidies in California between 2020 and 2023, the study found that the inclusion of one additional public funding source is associated with an additional four months of predevelopment and $20,460 in per-unit total development costs, even after controlling for a variety of project characteristics such as project type or population served. Projects with three to five additional public funding sources take nearly two years, on average, between the first funding application and their LIHTC award. Especially in today’s inflationary environment, added time translates into added costs.

The goal of the GRP is to create a more efficient system for delivering scarce public resources to affordable housing developers, who are the primary users of the system. These reforms are intended to save those projects both time and money, which should result in more affordable housing getting built. The GRP is one key step in the process toward a more streamlined affordable housing delivery system. The GRP will also reduce the California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD)’s overall portfolio, allowing it greater focus on priorities such as housing policy and planning, building codes, and manufactured housing oversight.

Specific opportunities for governance reform associated with a GRP

We conducted focus groups and interviews with over 60 housing experts around the state in the first quarter of 2025 to better understand stakeholders’ ideas on how to improve the State’s housing system. Overwhelmingly, the respondents named the same challenges: fragmentation; lack of consistent goals across agencies; bureaucratic delays; and an overly drawn out, often duplicative, process for securing funding.

Specifically, interviewees identified the following goals for any reorganization effort:

- Cabinet-level leadership on housing and homelessness policy and programs commensurate with the issues’ importance at the State level.

- A seamless process for securing all State funding commitments at once rather than having to apply sequentially to multiple State agencies over a six- to 18-month period in order to fully fund a project. Critically, this includes the California Debt Limit Allocation Committee (CDLAC) and California Tax Credit Allocation Committee (TCAC), in addition to HCD and the California Housing Finance Agency (CalHFA).

- A substantially improved process for closing on State-funded loans to increase consistency and predictability.

- A coordinated and efficient system for compliance and asset management instead of the current system of different agencies all seeking similar information but in different forms.

Interviewees indicated multiple ways to achieve such a vision, but two core elements consistently surfaced:

- Shared governance structure:

- A single oversight body should be established, ideally headed by someone whose sole focus is affordable housing finance, and modeled on the elements within TCAC that seem to be working well (e.g., consistent response times, objective criteria for awards, transparent process for appeals, and problem-solving attitude among staff).

- This oversight body should align awards criteria and processes to eliminate the multi-step processes that occur today.

- This oversight body should provide greater transparency and timeliness to the processes by which awards criteria are determined and developers seek appeal of unfavorable decisions.

- Administrative reform:

- Leadership should have expertise in affordable housing finance and development and exercise significant authority to address the inconsistencies in timing and interpretation that users say they experience today.

- Wholesale improvements to loan closings should be made—for example, by moving the legal review process under a focused department that only does affordable housing finance and development work.

- A single department should implement compliance and asset management activities, rather than having multiple state entities duplicate compliance and asset management functions.

Background: How does affordable housing get developed in California?

It is difficult to understand these recommendations without having a clear sense of how affordable housing projects are developed and financed today. To begin with, most affordable housing developments[3] rely on some degree of public funding or tax credits to be financially feasible. Generally speaking, affordable housing developments need subsidized capital or operating funds because the affordable rents or sales prices do not support market-rate financing.

All of these operating or capital subsidies are limited, and demand typically significantly outstrips supply. According to the California Housing Partnership (CHP), the State is only funding 15 percent of what is needed to meet its goals.[5] Many people assume that the developments are funded by the federal government through the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). In fact, the vast majority of resources specifically to support new construction in California are administered at the state or municipal level, even if they draw on Congressionally appropriated resources.

Role of the State

The State has four housing funding entities—each of which has unique roles, administrative staff, program regulations, and governance systems.

- California Department of Housing and Community Development (HCD): HCD is the State’s main housing policy department and the principal source of General Fund or General Obligation bond funding for affordable housing development. HCD is also the passthrough entity for certain federal housing block grant funds such as HOME. HCD is overseen by a director appointed by the governor and reporting to the secretary of BCSH.

- California Tax Credit Allocation Committee (TCAC): Chaired by the treasurer, the committee oversees the allocation of federal Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC). The “committee” is actually the governance structure, while the staff reports through an executive director to the treasurer. There are two LIHTC variations: 4 percent credits and 9 percent credits. The amount of 9 percent tax credits is determined by a federal formula. The 4 percent tax credit program is not allocated by the same formula, but is limited by federal regulations that tie the availability of credits to users of the Tax-Exempt Bond Program administered by CDLAC. TCAC is overseen by a director appointed by the treasurer.

- California Debt Limit Allocation Committee (CDLAC): Chaired by the treasurer, the committee oversees the allocation of tax-exempt bonds for a variety of uses (such as affordable rental housing, recycling and disposal facilities, and infrastructure projects). Like TCAC, the committee itself is the governance body, and the administrative staff report to the treasurer. Historically, CDLAC has apportioned over 90 percent of the available bond cap to multifamily affordable housing. Under the LIHTC program, any project that receives a tax-exempt bond allocation is entitled to use the 4 percent LIHTC credits, provided that the project uses tax-exempt bonds to finance at least 50 percent of the project costs. CDLAC is overseen by a director appointed by the treasurer.

- California Housing Finance Agency (CalHFA): Overseen by an appointed board, CalHFA is an issuer of tax-exempt bonds, receiving a direct annual allocation from CDLAC. CalHFA issues bonds for both single-family and multifamily housing. CalHFA also has a limited number of state-subsidized direct funding programs, most notably the Mixed-Income Program, or MIP. In recent years, the legislature has directed CDLAC to allocate CalHFA enough tax-exempt bond authority so that every recipient of MIP funds qualifies for 4 percent tax credits automatically. CalHFA is overseen by a director appointed by the governor and reporting to the CalHFA Board of Directors.

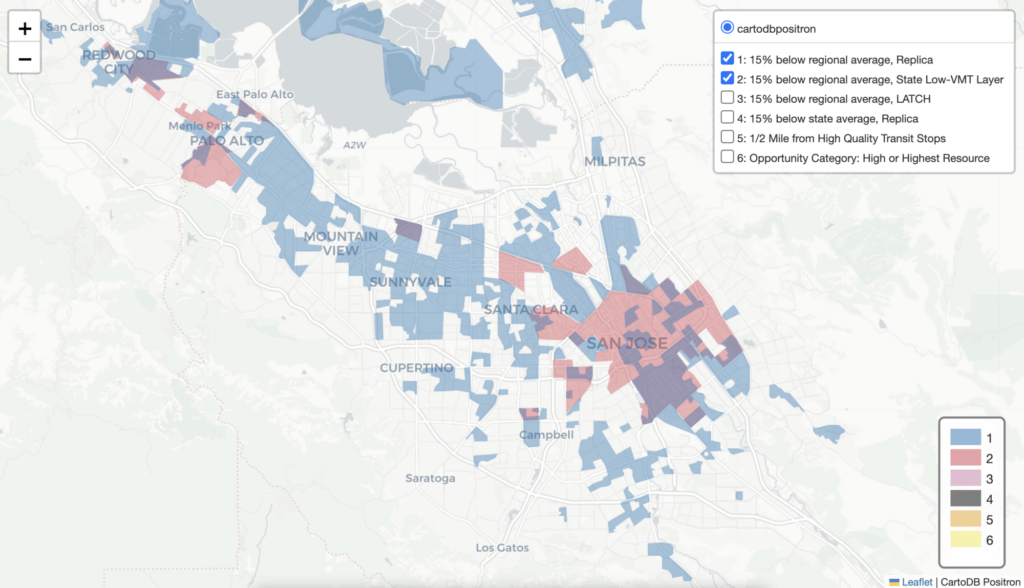

In order to determine which developments to fund, the various state housing agencies each have unique competitive processes. While HCD, TCAC, and CDLAC have attempted to maintain definitional consistencies around core elements such as income levels and affordability standards, each program has a unique scoring system with distinct incentives for over a dozen factors, including production costs, income targeting, locational preferences, and service amenities. Because these competitions reward projects that leverage non-State resources, many developers only seek State funding after securing private financing commitments and/or funding from local sources.

Role of county and municipal government

Counties and cities also play a significant role in the development of affordable housing. Local governments grant land use and building permits to develop housing. They also play a role in funding and can provide surplus public land to developers of affordable housing. Given these roles, many affordable housing developments start their search for resources at the local level.

- The largest California cities typically have their own housing departments with locally administered funding, while smaller cities either rely on County- or regional-level departments that also work in the unincorporated parts of counties.

- Some local housing departments rely on “self-help” tax measures to create funding resources for affordable housing. Examples include Los Angeles’s recently approved Measure A, San Mateo County’s Measure K sales tax, and San Francisco’s General Obligation bond program.

The current multi-step process for funding a housing project

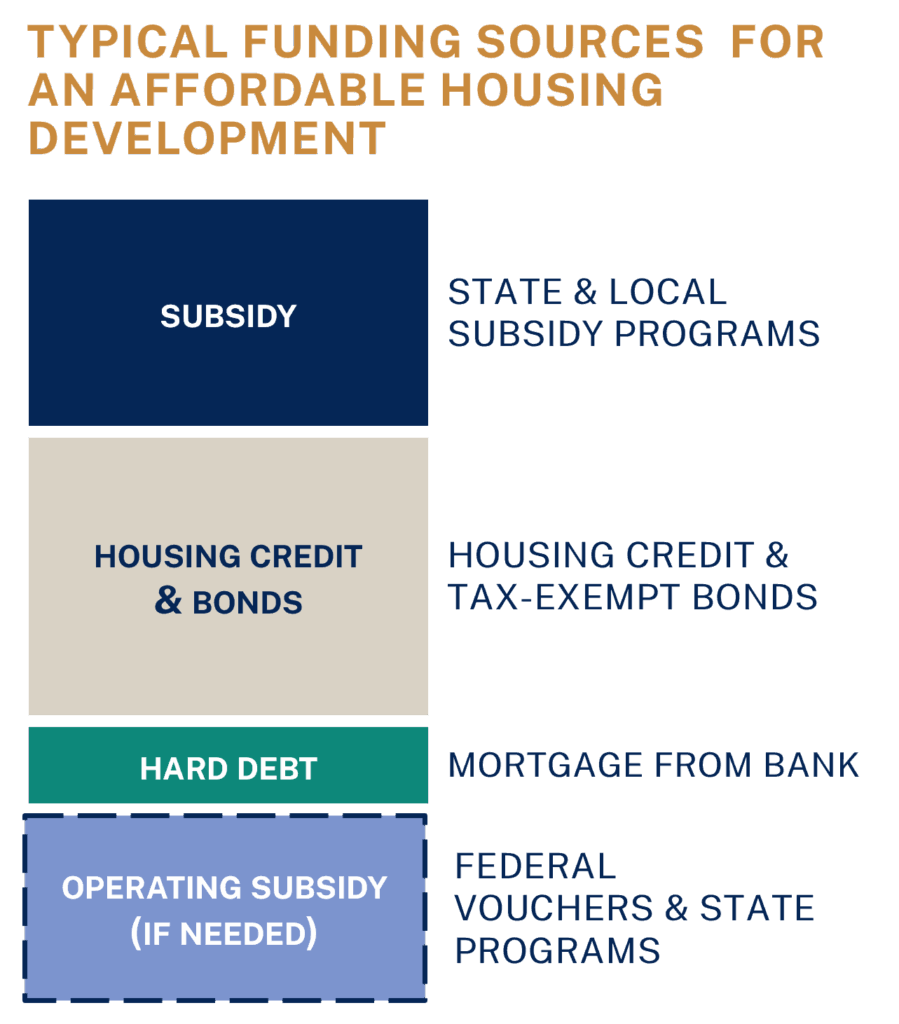

A typical affordable housing project in California assembles four to six types of funding from a variety of state and local sources, often referred to as the “capital stack.”[6] Under the current fragmented system, a developer seeks each of these funding sources separately in a roughly linear process starting with subsidy. In other words, the development often must secure the awards in a particular order because the project cannot successfully compete for the next funding source without that prior award.

Source: Enterprise Community Partners

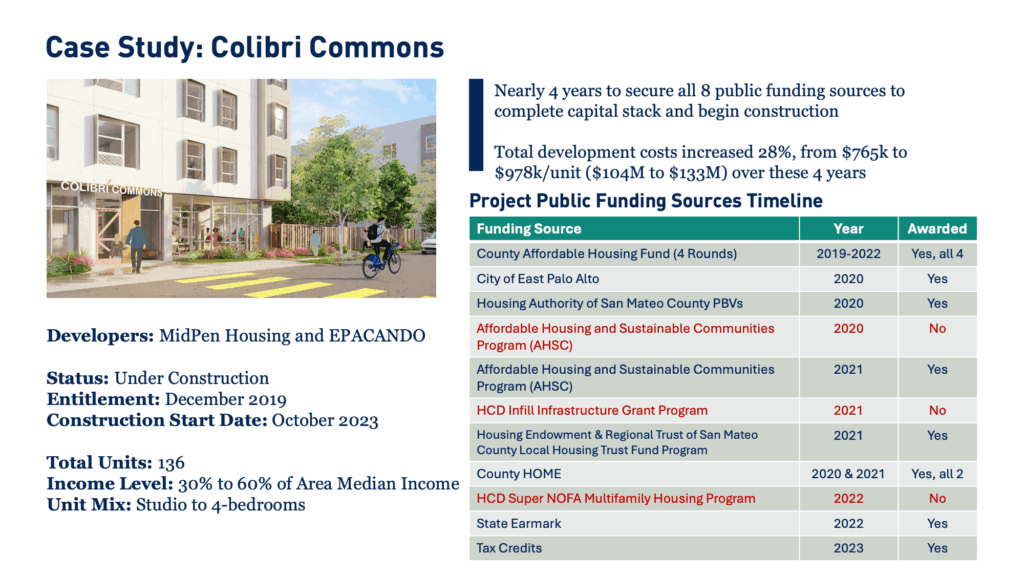

MidPen Housing and EPACANDO’s experience of developing Colibri Commons, a 136-unit affordable community in East Palo Alto, illustrates how this process plays out and the challenges that affordable housing developers encounter (see graphic). This development was entitled and received local funds in 2019; however, construction didn’t begin until October 2023. It took four years to secure all of the State funding sources needed to assemble the development’s capital stack. The process was lengthy and unpredictable, with multiple attempts at securing various sources, including Affordable Housing and Sustainable Community (AHSC) funding on the second attempt and no success with securing an Infill Infrastructure Grant or funding. In 2022, Colibri Commons secured a State earmark, allowing it to successfully apply for tax credits in 2023, and begin construction.

Source: Bay Area Housing Finance Authority, Enterprise Community Partners, MidPen Housing

Source: Bay Area Housing Finance Authority, Enterprise Community Partners, MidPen Housing

As this example illustrates, if at any point in the process, the developer is unsuccessful at securing either HCD or CalHFA funding, the project has to reapply in the following round before applying for tax credits and bonds. This delay can take anywhere from six to 18 months because of the timing of the financing applications. For example, HCD only has one annual Super Notice of Funding Availability (NOFA), and they do not always issue their awards with enough lead time to enable applicants to apply for the next round at CDLAC or TCAC.

Opportunities for proposed reform to respond to stakeholder concerns

The benefits from reform loosely fall into two categories: 1) impacts from possible governance changes on entities within the control of the governor, and 2) impacts of a broader reform that incorporates actions by entities under the treasurer.

The current GRP includes reforms that would solely impact entities currently under control of the governor. These reforms are intended to have the following benefits:

- Significantly increase transparency into the awards, regulatory, and appeals process. This would also improve confidence in the State’s housing agencies among users, elected officials, and others.

- Reduce the time and cost related to loan closings. Because the HCD loan closing occurs after the project has drawn down its full construction loan amounts—meaning that the developer is paying interest on those funds—delays are extremely expensive. For medium to large projects, six months of delay at full draw-down generates hundreds of thousands of dollars of unnecessary interest expense per project.

- Improve the awards process for funding projects. To date, the goal of Assembly Bill (AB) 519 (Schiavo) to establish a “one-stop shop” has not been realized. Although HCD has created a Super NOFA process, the awards process has still left projects partially funded and in need of additional HCD funding. Providing the Housing Development and Finance Committee with authority and oversight is part of the solution; ensuring that organizational leadership has expertise and focus on financial transactions is another component of improving alignment.

- Reduce the cost of compliance for state agencies as well as property operators. There is clear duplication of effort, with staff from multiple agencies overseeing compliance and asset management reviews for each project. This duplication also results in higher staffing costs at affordable housing properties, which reduces the net operating income available to run properties and reduces the borrowing capacity of projects in development.

If the State were to incorporate TCAC and CDLAC as part of its restructuring, there would likely be additional benefits:

- Reduce the time and cost associated with financing development. While State-level reform can’t fix all of the system fragmentation, it would have a major impact. According to a 2021 California Housing Partnership report, 86 percent of affordable homes in developments awarded LIHTC need funding from two or more State housing finance agencies.[7] Consequently, creating a “true” one-stop shop at the State level could be expected to shave six to nine months off the timeline for a typical project.

- Deepen the impact of State housing policy and alignment. Given the fact that State resources are inherently limited, it is critical that funding programs produce their desired impacts. With so many competing policy goals expressed in the funding competitions, this impact is distorted. In addition, it is harder to switch focus or emphasis when needed. For example, if the State does not have state resources available for a particular housing goal in a given budget cycle (e.g., serving seniors), the State could redirect federal credits and bonds to those housing types that do have access to resources during that period of time (e.g., serving veterans).

The GRP is an important first step to creating a better housing delivery system. As our focus groups and interviews have shown, there are many opportunities to expand upon the current reorganization proposal over the coming months and years. This increased efficiency should be paired with significant and consistent affordable housing funding in order to deliver the affordable housing that Californians need.

Endnotes

[1] National Low Income Housing Coalition, Out of Reach. https://nlihc.org/oor

[2] National Alliance to End Homelessness. (2024). State of Homelessness: 2024 Edition. Retrieved from: https://endhomelessness.org/state-of-homelessness/

[3] Reid, C. & Tran, T. (2025). Reducing the Complexity in California’s Affordable Housing Finance System. Terner Center for Housing Innovation, UC, Berkeley. Retrieved from: https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/blog/reducing-the-complexity-in-californias-affordable-housing-finance-system/

[4] The term “affordable housing” is used here to mean housing that has a long-term legal obligation to provide people at specified income levels with rents or sales prices generally at 30 percent or less of those incomes. This designation is distinct from housing that is affordable to lower- or moderate-income people without any such legal restrictions.

[5] California Housing Partnership. (2025). California Affordable Housing Needs Report 2025. Retrieved from: https://chpc.net/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/CHP_State-Housing-Needs-Report-2025.pdf

[6] Kneebone, E. & Reid, C. (2021). The Complexity of Financing Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Housing in the United States. Terner Center for Housing Innovation, UC Berkeley. Retrieved from: https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/blog/lihtc-complexity/#:~:text=The%20authors%20find%20that%20on,the%20rise%20of%20development%20costs

[7] California Housing Partnership. (2021). Creating a Unified Process to Award All State Affordable Rental Housing Funding “One-Stop Shop.” Retrieved from: https://chpc.net/creating-a-unified-process-to-award-all-state-affordable-rental-housing-funding/