California’s Homekey Program: Unlocking Housing Opportunities for People Experiencing Homelessness

Published On March 17, 2022

A new report explores lessons from the first round of funding for California’s Homekey initiative, an innovative program to address homelessness by dramatically increasing funding for permanent supportive housing. Authored by our Faculty Research Advisor Carolina Reid, Senior Research Associate Ryan Finnigan, and Research Assistant Shazia Manji, the report California’s Homekey Program: Unlocking Housing Opportunities for People Experiencing Homelessness offers seven case studies on local approaches, including Los Angeles, Fresno, Oakland, and Riverside, and gives a robust portrait of how the Homekey 1.0 funding has been deployed and how service providers, developers, and local agencies are implementing the program on the ground.

Below find a summary blog from the author, our Faculty Research Advisor Carolina Reid.

As recently as five years ago, an overwhelming majority of the funding directed at addressing homelessness in California came from the federal government, with little state involvement. The rising number of people who were experiencing homelessness—the majority of them unsheltered—was left to local jurisdictions to address, with little attention from the state legislature or agencies.

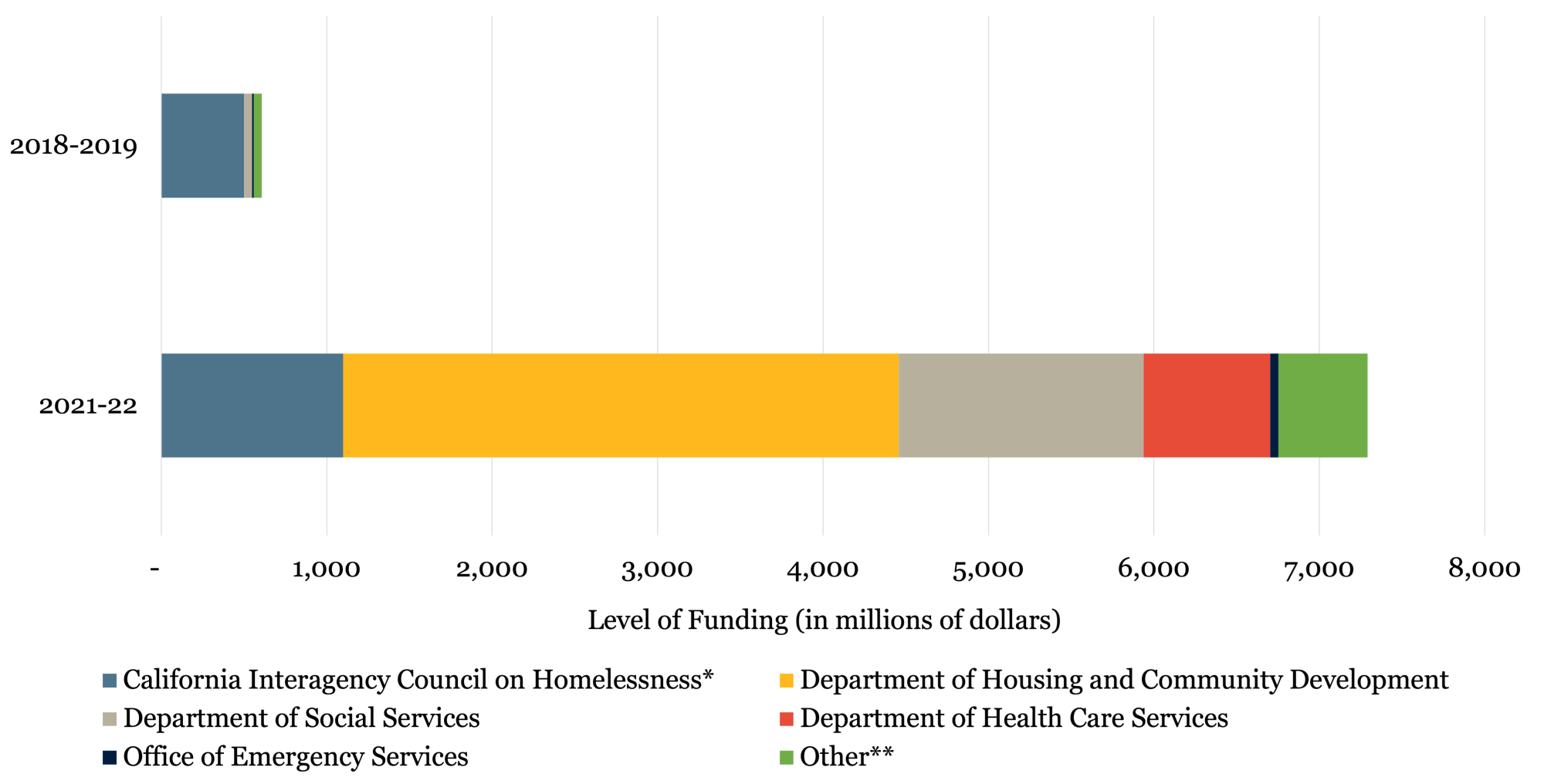

That tide has turned, as evidenced by the state’s commitment of unprecedented levels of funding to address homelessness as well as its willingness to pilot new, innovative programs across state agencies (Figure 1). Our latest research paper, California’s Homekey Program: Unlocking Housing Opportunities for People Experiencing Homelessness, focuses on the lessons learned from Homekey, one of the most significant programs through which the state has stepped up its investments in addressing homelessness. Sometimes confused with Project Roomkey—which leased rooms in hotels for temporary shelter during the pandemic—Homekey seeks to address homelessness by dramatically increasing the supply of permanent affordable housing across the state.

Figure 1: California State Funding Dedicated to Addressing Homelessness

Source: California Budget Summaries, 2018-2019 and 2021-22

* Formerly the Homeless Coordinating and Financing Council.

** Includes Department of State Hospitals, Veterans Affairs, Department of Transportation, California Community Colleges, California State University, and University of California.

The program has already had a significant impact. Developed in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, Homekey provides local public entities with large, capital grants that can be used to purchase existing buildings and convert them into housing for people experiencing or at risk of homelessness. In the first round of funding, often referred to as Homekey 1.0, the state issued approximately $800 million in grants to 94 projects, the majority involving the purchase of hotels and motels that had been hard hit by the pandemic. All told, Homekey 1.0 added 6,000 rooms and/or units to the state’s supply of interim and permanent housing in under six months, at an average initial cost of $238,000 per unit. This alone is a significant accomplishment, especially when compared to the time and costs it typically takes to build affordable housing. It is also worth recognizing the herculean efforts of staff across the state—at California’s Department of Housing and Community Development, in city and county agencies and departments, and in nonprofit and community based organizations—who pulled this off during the pandemic without an existing road map for how to do this work.

As the state gears up to continue investing in Homekey, with $1.45 billion authorized for this fiscal year, important lessons can be learned from the first round of the program. We find that Homekey’s grant structure–coupled with giving jurisdictions flexibility in how to use the funds–allowed them to move quickly to respond to local needs. In stark contrast to the way in which affordable housing usually gets funded, Homekey also reduced the need to put together multiple funding sources (which adds time and costs) to make projects feasible. Homekey’s emphasis on speed—facilitated by regulatory streamlining—made all the difference in how quickly localities were able to get people housed. We also find that Homekey 1.0 generated new partnerships and strengthened old ones, and in some places, helped to improve coordination across city and county agencies.

But more must be done to ensure that the program has its intended impact over the long-term. For all its strengths, Homekey remains embedded within an underfunded and fragmented affordable housing system. This means that many properties do not have sufficient funding to support long-term operations—this remains the single largest challenge and concern for Homekey grantees. Some buildings also need a lot more work to be converted to permanent housing, but Homekey’s grants weren’t large enough to cover needed renovations. Securing additional funds for converting those sites is difficult and can introduce new regulatory barriers and requirements. The resources to support resident well-being—including case management, health care, and mental health and/or substance use counseling—also remain well below need.

None of these challenges are easily solved, and the history of affordable housing policy is filled with examples of ambitious programs failing due to the lack of an ongoing commitment to funding, implementation, and systems reform. However, the state has shown through the Homekey program that it can quickly initiate ambitious new programs that meet the urgency of California’s homelessness crisis. It should continue to demonstrate that same ambition and ensure that the long-term implementation of Homekey is as successful as its promise.