California’s Rent Cap Debate: Something’s Gotta Give

Published On August 1, 2019

The Terner Center for Housing Innovation first became involved in discussions around rent control policy in California leading up to Proposition 10, the ballot initiative in 2018 (ultimately defeated) that would have repealed the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act, the statewide framework put in place by the state legislature in 1995 to set limitations on local rent control ordinances. History tells us that the debate over Costa-Hawkins itself was a divisive and hard-fought battle. It’s no surprise that stakeholders and policymakers are having a difficult time finding a path forward today.

In May 2018, after research and meetings with a variety of stakeholders, the Terner Center released a brief Finding Common Ground on Rent Control. The purpose of this brief was to outline policy measures that 1) appeared to have the broadest conceptual consensus from varied stakeholders and thus provided a basis for negotiating a legislative solution and 2) could thread the needle between the desire to protect tenants from rental increases and displacement while at the same time recognize the critical need to ensure continued new construction and investment in rental housing. There is no question that ultimately the housing affordability challenges in California require that more homes and apartments be built quickly and in a cost-effective manner.

The brief tested four potential concepts. The one that had the most potential for agreement among stakeholders was the “anti-gouging” cap on rent increases. This concept was, at least in part, the basis for Assembly Bill 1482, introduced by Assembly Member David Chiu. Around the same time, the Bay Area CASA Compact also used elements of this concept and refined it into a legislative intention document. The CASA Compact included some very specific provisions to ensure flexibility of a rent cap in times of extreme inflation, economic distress, or major capital improvements. This included the ability to pass through additional rent increases up to a certain, separate cap after an economic downturn (according to a banking formula), actual increases in public charges including utilities and property taxes, and amortized capital improvements allowed under IRS rules. CASA did not develop the actual formulas for these pass-throughs, and envisioned a rent cap that was fixed in duration (15 years).

Where We Are Today

Recently, in response to a number of significant amendments to AB 1482 prior to its most recent hearing in the Assembly Judiciary Committee, the Terner Center released a new brief, Curbing Runaway Rents: Assessing the Impact of a Rent Cap in California. We concluded in the brief that, overall, even though the rent cap was increased from CPI plus 5 percent to CPI plus 7 percent, and curtailed some of its scope on single-family homes, the bill would still protect as many as 4.6 million households not covered today. Assembly Member Chiu should be commended for working hard to find a common ground solution so that these protections can be realized given the extraordinary pace of rent increases in recent years.

Yet more work needs to be done, in a very short window, to have this legislation realized. While the bill narrowly passed the Judiciary Committee, further action is needed to better balance protections with production concerns. Those concerns include 1) first and foremost, not impeding new construction; 2) a lack of certainty—especially for potential investors in future development projects—that, if these caps are agreed to, they won’t be changed in the future; and 3) the need for a “safety valve” in times of stress (e.g., market downturns, unforeseen new government code or regulatory cost or tax increases, and water/power and other utility cost increases). These concerns are inter-related as changes in language in the bill (or lack of language addressing the concern) on one can impact the others.

Recent amendments to the bill have exacerbated these concerns. The decision to sunset the bill in 3 years, paired with the new provision exempting developments built 10 years prior to the bill’s adoption, has led to concerns that the intent may be to extend the rent cap beyond the 3 years and initiate a “rolling” rent regulation on new buildings within 10 years of placing them in service. Rolling rent regulation was one of the proposals we tested in our earlier May 2018 brief. We came to the conclusion then that there is a wide gulf between renter advocates and developer and owners regarding the window for rolling inclusion. For renters and advocates, 10 years is the longest that could be considered. Concerned that too narrow a window would have a chilling effect on investment, developers and owners held a wide range of views, starting at 20 to 40 years—although for some, there is no window that would be acceptable.

We are not aware of any study evaluating a long term rent cap such as the one proposed by California and covering new construction. The development and financial community are concerned that a “rolling rent control” would raise the specter of closing off new construction funds. This heightened risk, on top of already thin return margins due to rising construction costs, could lead to “capital flight” from California housing into other assets that have more certainty of returning capital profitably over the useful life of the invested asset. A rent cap policy that risks capital flight from housing could significantly reduce or stall out new housing construction in California—with dire impacts on long-term affordability.

Where to Go from Here

It is possible to design a rent cap bill that would address these issues. On this core tension of passing a bill that protects tenants without inhibiting new construction and investment, I see three options:

- Exempt new construction from AB 1482

- Build out language that provides a “safety valve” to building owners/investors

- Take on and resolve all of the outstanding issues now, for a longer-term (not 3-year) rent cap

Option 1- Exempt New Construction

This option would mean amending the bill language to remove the 10-year exemption and specifying that, moving forward, new construction would be exempt from the rent cap. This option is the simplest to do in the short run. It has merit since AB 1482 sunsets in three years. Given that limited timeframe, taking out the provision that creates a 10-year exemption would have no immediate negative impact on newly constructed buildings, yet would extend immediate protection for tenants at a time of crisis.

The downside for this approach for those who want rolling rent regulation is that, without the 10-year exclusion, just “extending” the law after 3 years would not extend rent cap regulations to previously excluded buildings.

Given the stalemate and lack of consensus on this issue, exempting new construction and “punting” on the rolling inclusion issue is an appropriate short-term response.

Option 2- Provide a Safety Valve

Adding language to the bill to provide a safety valve for the type of unforeseen circumstances discussed above is no easy task. The first decision is whether such provisions are adjudicated building by building through administrative procedures laid out in the bill and implemented via a state or other agency. Such an approach would be costly and take considerable time to put into place. It would require extensive data collection (even more than the rental property data registry proposed in Assembly Bill 724, proposed by Assembly Member Buffy Wicks and which failed to win enough votes to proceed from the Appropriations Committee, partly based on concerns about its cost).

The alternative is to create standards or “triggers” that if met, are automatically available to the building owner, and thereby self-regulating. Examples of such triggers could be:

- Inflationary Times: If the regional CPI (and we strongly recommend regional CPI, not the statewide CPI as this could vary dramatically by submarkets), goes above 10% for more than six months, then the 10% cap would increase by up to 2 additional points until it has fallen below the 10% threshold again. There are of course many discussions to be had and formulas to evaluate with such a trigger, such as the timeframes and the added cushion provided.

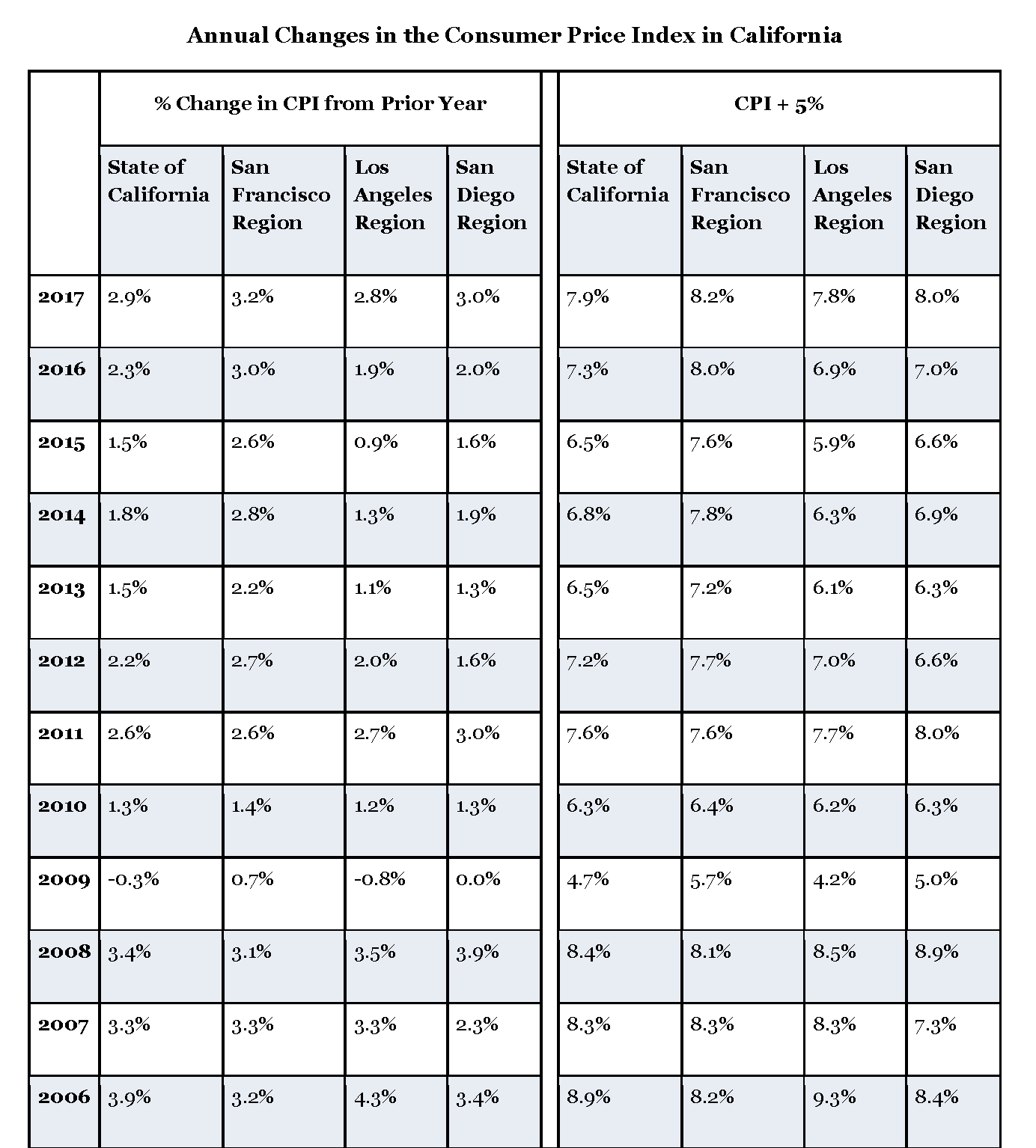

- Economic Distress: In recessionary times (and these again could occur on a regional and not statewide basis), building owners may have years (as happened during the Great Recession) when they are not able to raise rents and not able to adequately cover expenses. As our historical data (Figure 1) demonstrate, 2010 and 2011 were years the CPI was negative. Building owners are unlikely to be able to raise rents much, if at all, during these times if the real estate market, job market, and wages are negatively impacted. Therefore, building owners could be eligible to “bank” some or all of the rent increases they are unable to charge during this period. Again, there are many nuances that would need to be determined for this trigger, including how quickly owners could use any “banked” rents to avoid rent shocks when the market recovers. The original CASA proposal recommended that landlords should be able to bank unused rent increases for 3 to 5 years and, when drawing on banked increases, landlords should not be able to raise rents more than 10 to 15% annually.

Figure 1:

These two triggers do not cover all of the possible unforeseen circumstances that may arise including a local or state imposed a new requirement on building owners (seismic retrofits, energy efficient upgrades) or simply a large building system failure or necessary capital improvement. These situations are less predictable and finding a self-regulating trigger is more difficult.

This strategy has significant merit as it provides a safety valve that could garner support from apartment owners. The primary, and not insignificant challenge, is forging consensus on these complicated provisions (and getting them right) in such a truncated period of time.

Option 3—Address Underlying Concerns Now for a Longer-Term Cap

While the two options above could solve a core issue for a number of stakeholders and perhaps garner enough votes to move forward, neither of these options will satisfy everyone. The remaining alternative is to find a compromise that solves the broader issues that led to making AB 1482 a short-term 3-year bill. That means addressing the fear that the rent cap law would create a new battle year after year as participants on all sides advocate for amendments, including lowering what is meant to be an “anti-gouging” cap to create stricter rent controls.

As enticing as this option may be for some, it is hard to imagine forging a consensus on these outstanding issues in any short order. If this option is pursued, the risk is that the status quo will continue unabated and the opportunity to create certainty will actually have been missed. Rental tenant protection advocates will not give up trying to make change through ballot initiatives, and the owners and developers will continue to spend money to defeat such efforts. But what will change for tenants in the meantime?

Conclusion

When it comes to the state’s housing crisis, the stakes are high, and there are no easy answers or silver-bullet solutions for policy-makers. The Terner Center encourages the use of data to guide decision-making whenever possible and to be cautious with creating uncertainties that could unintentionally worsen the crisis for residents over time by chilling investments in rental housing that is so badly needed in California. But something needs to be done to address the severity of today’s crisis: year-over-year rent increases and extraordinary rent increases are untenable and unsustainable. The status quo must change, and it will take both near-term and longer-term solutions to make that happen. A statewide anti-gouging rent cap could provide one tool to immediately address the worst effects of the crisis for millions of Californians, and do so in a way that does not stymie future production of much needed housing. There is still a possibility for a compromise on a bill that could begin to change the status quo, but the clock is ticking.