Making It Pencil: Can We Get Housing for Middle-Income Households to Work?

Published On May 16, 2024

Authors: David Garcia, Ben Metcalf

For middle-income Californians, the state’s housing supply and affordability challenges have been more acute in recent years. Between 2010 and 2019, the share of middle-income renters in California who were cost-burdened (i.e., the share of households paying more than 30 percent of their income in housing costs) increased by roughly 9 percentage points, from 40 to 49 percent. While the state has invested significantly in affordable housing for low-, very low-, and extremely low-income households, there are relatively few programs that incentivize housing that is affordable to middle-income families. Moreover, private-market developers are generally unable to build new housing that is attainable to these residents given the high cost of development and the need to satisfy minimum return on investment requirements for capital partners.

Can policymakers change this dynamic? In the long run, an increase in overall housing supply is the key to moderating prices for all households, including middle-income renters. In the short term, there have been efforts to focus specifically on middle-income supply, such as through Joint Powers Authority (JPA) efforts to acquire existing housing and restrict rents to prices affordable to middle-income households as well as recent changes to state law which allow for middle-income units to qualify for the state density bonus. But these targeted efforts are not enough to meet the need.

There are a range of policy changes that would enable market-rate housing developers more broadly to deliver homes to middle-income residents without the need for direct government subsidization. But it can be hard for policymakers to determine which interventions would be the most impactful. In 2023, we published “Making It Pencil: The Math Behind Housing Development,” which modeled what policy and economic changes would be needed to make more market-rate housing development financially feasible. In this commentary, we apply the “Making It Pencil” financial modeling to examine what policy changes are most likely to be effective in allowing more middle-income projects to be built by the private market without direct subsidy.

Setting Rents at Middle-Income Levels: Will It Make a Difference?

Although middle-income renters in California are increasingly facing rent burdens, there are also some places where housing affordable to this demographic aligns relatively well with market rates. This would mean that a policy designed to restrict rents for middle-income households would not be needed. For our first analysis, we asked: does restricting rents in a new housing development deliver more affordable rents than what would otherwise be charged in newly-built housing?

To do this, we compared current market-rate rents that we used in our Making It Pencil proformas to what rents would be if they were set at 100 percent of Area Median Income (AMI). Figure 1 shows the results for the East Bay, Los Angeles, and South Bay regions. The analysis shows that market-rate studios are generally priced at levels below 100 percent of AMI in all three markets, and therefore generally affordable to middle-income households. However, the market is not producing one- and two-bedroom apartments that are affordable to middle-income households in the East Bay and Los Angeles.

In the South Bay, rents affordable to households making 100 percent of AMI are actually slightly higher than or comparable to market rate rents; only the hypothetical two-bedroom limited to 100 percent of AMI would see a discount when compared to market rate. This does not mean that new market construction would be “affordable”—rather, it shows that in many Bay Area markets, median incomes are extremely high, pushing up the rent levels that are considered affordable to people who live there, which may not be the case for people who work there. Restricting units for those earning middle incomes can make it more likely that such units will be affordable for some of those who work in the community but cannot otherwise afford to live there, therefore potentially improving the jobs-housing balance. In addition, restricting rents to middle-income levels would also have the benefit of keeping rent levels controlled over time, ensuring that tenants are not subject to volatility as these rents would only be allowed to rise at the same rate as increases in area median income.

Figure 1: Comparison Between Market-Rate Rents and Rents Affordable to Median-Income Households in Three California Markets

South Bay (e.g., Downtown San Jose, Santa Clara)

| Unit | Assumed Market-Rate Rent | Rent Limit Affordable to Households Making 100% of AMI | Discount to Market |

| Studio | $1,819 | $3,172 | – |

| 1 bed | $2,985 | $3,398 | – |

| 2 bed | $4,208 | $4,080 | 3% |

East Bay (e.g., Downtown Oakland, Emeryville)

| Unit | Assumed Market-Rate Rent | Rent Limit Affordable to Households Making 100% of AMI | Discount to Market |

| Studio | $2,138 | $2,590 | – |

| 1 bed | $3,493 | $2,774 | 20% |

| 2 bed | $4,488 | $3,330 | 26% |

Los Angeles (e.g., Westwide, Hollywood)

| Unit | Assumed Market-Rate Rent | Rent Limit Affordable to Households Making 100% of AMI | Discount to Market |

| Studio | $1,988 | $2,228 | – |

| 1 bed | $3,016 | $2,523 | 16% |

| 2 bed | $4,114 | $2,838 | 31% |

We also find that it is unlikely that the market will produce units affordable to middle-income households without policy intervention. When we set rents at 100 percent AMI levels in our development proformas (which include a mix of studios, one-bedroom, and two-bedroom units), we find that the projects become financially infeasible for the developer. In a previous report on development math, we define feasibility as yielding at least one percentage point higher than area capitalization rates for an occupied, similar building in the same area. For more information on the math that goes into housing development, see our prior study here.

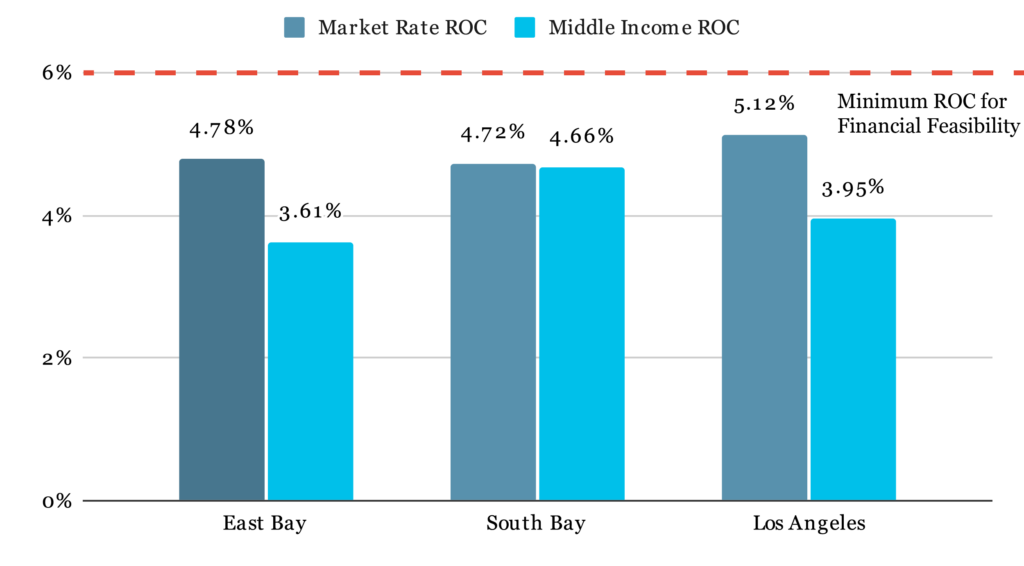

For a project to be financially feasible in today’s market, it would roughly need to meet or exceed 6 percent return on cost (ROC). Figure 2 below shows the expected return on cost for the prototype market-rate and middle-income developments; the Los Angeles and East Bay projects have the starkest difference in the potential ROC. The South Bay spread is much smaller—4.72% compared to 4.66%—likely due to the relatively high allowable rents in that region, which are much closer to market rates.

The challenges of building new housing is not limited to just middle-income units. As we detailed in our 2023 study, even new developments pegged at market rents are unlikely to be financially feasible, as high construction costs, interest rates, and restrictive housing policies push development costs higher than market rents can cover. The differences between our market-rate and middle-income pro formas, however, demonstrate how it is even more difficult for private market developers to deliver housing that is affordable to middle-income households absent policy interventions.

Figure 2: Comparison of Return on Cost Between Market-Rate and Middle-Income Pro Formas

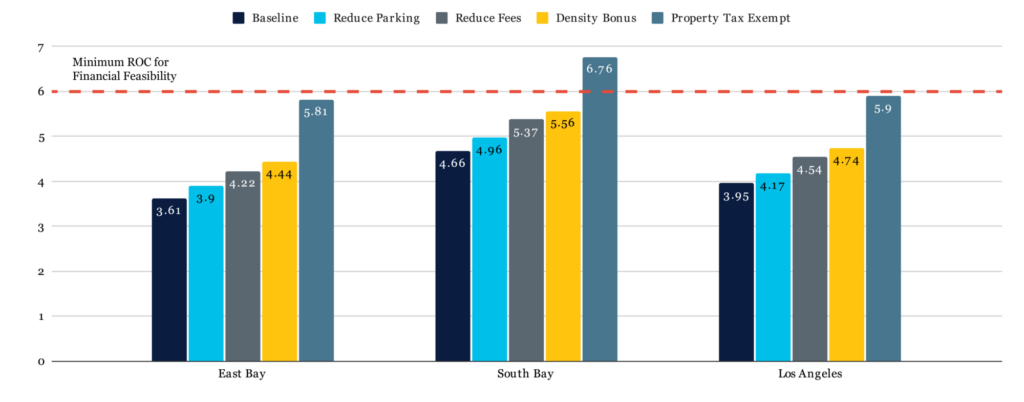

What policy changes would it take to make middle-income housing developments closer to feasibility? We tested the cumulative impacts of reducing parking (from a requirement of one space per unit to .25 spaces per unit), reducing fees (from $40,000 per unit down to $10,000) and increasing density (a 50 percent increase as allowed by state Density Bonus Law). All of these boost the ROC for the projects slightly (Figure 2). We then also added the impacts of a property tax exemption, which is what affordable housing projects receive when rents are limited to 80 percent of AMI. In each region, adding this incentive brought development closer to feasibility, though not always enough to assure that the project would be able to get financing.

What policy changes would it take to make middle-income housing developments closer to feasibility? We tested the cumulative impacts of reducing parking (from a requirement of one space per unit to .25 spaces per unit), reducing fees (from $40,000 per unit down to $10,000) and increasing density (a 50 percent increase as allowed by state Density Bonus Law). All of these boost the ROC for the projects slightly (Figure 2). We then also added the impacts of a property tax exemption, which is what affordable housing projects receive when rents are limited to 80 percent of AMI. In each region, adding this incentive brought development closer to feasibility, though not always enough to assure that the project would be able to get financing.

Figure 3: Middle-Income Return on Cost with Cumulative Policy Incentives

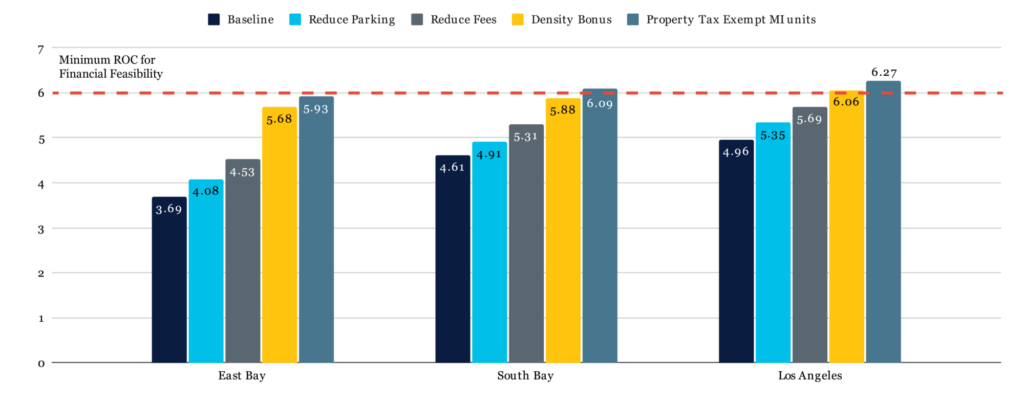

We also looked at a mixed-income option, where our prototypes included a mix of market-rate units as well as 33 percent of units held at rents affordable to households making 100 percent of AMI. As with the model where all units are restricted to middle-income households, we looked at the cumulative impacts of reducing parking and fees, increasing density, and exempting middle-income units from property taxes.With the right policies layered together, these projects work well in each region (Figure 4). We found that, cumulatively, these changes brought each mixed-income project to a ROC consistent with a high likelihood of development. Particularly impactful were the increase in allowable units through greater density in addition to the property tax reduction.

We also looked at a mixed-income option, where our prototypes included a mix of market-rate units as well as 33 percent of units held at rents affordable to households making 100 percent of AMI. As with the model where all units are restricted to middle-income households, we looked at the cumulative impacts of reducing parking and fees, increasing density, and exempting middle-income units from property taxes.With the right policies layered together, these projects work well in each region (Figure 4). We found that, cumulatively, these changes brought each mixed-income project to a ROC consistent with a high likelihood of development. Particularly impactful were the increase in allowable units through greater density in addition to the property tax reduction.

Figure 4. Mixed-Income Return On Cost with Policy Incentives

Conclusion

Incentivizing middle-income housing developments could open the door to more attainable homes for residents who are struggling to afford housing and who do not qualify for traditional subsidized homes. Our analysis finds that not one single policy change makes middle-income housing financially feasible to build, and that it will take several changes to get projects to feasibility. In particular, the recent changes to state density bonus law for middle-income housing appear to be quite powerful. Other changes we did not test could also be useful, such as entitlement streamlining, additional waivers for density bonus projects, or the ability to leverage alternative forms of financing. Of the policy changes we modeled, property tax exemptions appeared to make the largest impact on feasibility in all of the scenarios. But currently, property tax exemptions through the Welfare Property Tax Exemption are not available to developers for any units over 80 percent of AMI. For more middle-income projects to pencil, our analysis suggests that policymakers should consider providing a tax exemption for middle-income units.