The Cost to Build New Housing Keeps Rising: State Legislation Aiming to Reverse the Upwards Trend

Published On August 4, 2022

Authors: Muhammad Alameldin, David Garcia

The constraints on housing supply are a significant contributor to the current housing crisis. The median price for a home in California sits at $800,000, the highest in the country, and in the last decade, the state has failed to produce enough homes to keep up with job and population growth. Now coupled with rapidly rising interest rates, California’s homebuyers have lost significant purchasing power. For example, a family that could afford a home for $900,000 before recent interest rate increases can now only afford a home price of $650,000—resulting in over 25 percent less purchasing power as of May 2022 and this trend will likely continue to worsen. Instability in the buyers’ market directly impacts the building industry, with fewer homes being built since developers do not want to risk not selling newly constructed properties. At the same time, the cost of building materials continues to rise, leaving less financial capital to build new homes.

The largest driver of costs continues to be materials and labor. A recent investigation by the Los Angeles Times found that the cost of building several new affordable housing developments has ballooned to nearly a million dollars per unit. The projects included in the article are located in the Bay Area, which may now possibly be producing the most expensive affordable housing in the country. To be clear, the projects examined by the LA Times are outliers, and the per-unit costs of most affordable housing built in California does not cost nearly as much as those projects profiled. However, these projects are indicative of larger trends of the increased costs of building housing overall. Our research has illustrated that multiple factors contribute to the high cost of building in California. And these issues are not just limited to affordable housing: we have also shown that costs for market-rate projects have increased significantly over time. In our 2020 report, the per square foot hard cost to construct multifamily homes climbed 25 percent over the last decade after adjusting for inflation. The cost of wood, plastics, and composites rose by 110 percent after inflation, with finishes rising over 65 percent. The hard costs of a newly constructed home in California keep rising, with hard costs of building housing increasing by $68 per square foot compared to a decade ago. Since the report’s publication in 2020, these costs have only increased.

And while California generally leads the way in the development costs, prices are skyrocketing across the country, with residential construction costs rising by nearly 19 percent over the same period last year. These increases are driven by huge price increases for materials such as insulation, exterior finishes, and electrical components, which have all risen nationwide by about 10 percent in price in the last quarter alone. High interest rates are cyclical and determined by the Federal Reserve in response to the state of the overall economy. Rising construction costs are an annual trend, meaning fewer homes are going to be economically feasible to build, likely compounding housing affordability and supply for the long term.

So, what is California doing to address development and construction costs? The state has seen a flurry of legislative action in recent years—passing nearly six dozen laws since 2017—to spur greater housing production and affordability, but relatively few of those bills have tackled the issue of rising costs head-on. In the current session, several bills have been introduced with the goal of reducing costs either by lowering costs imposed by regulatory requirements or by targeting time delays that can add to costs.

Reducing Costs Imposed by Local Policies and State Regulation

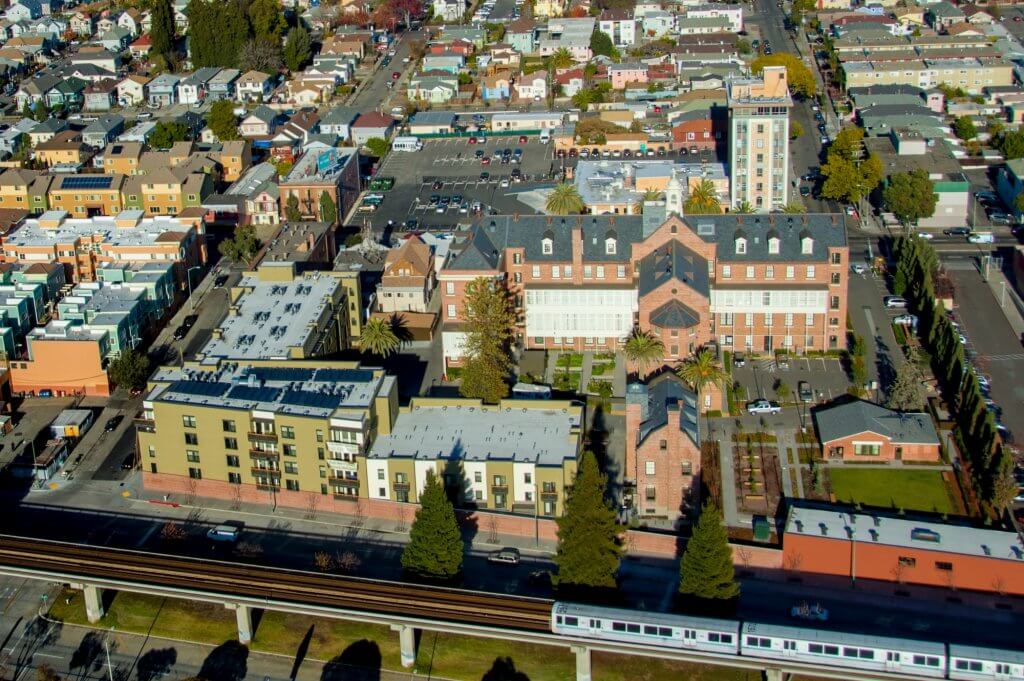

One of the most expensive components of home building can often be the parking required to go with it. For example, our 2020 report found that the presence of structured parking added nearly $36,000 per unit. Another study found that each parking space added per unit increased the development cost by 12.5 percent in urban areas. AB 2097 (Friedman, 2022) would tackle this specific cost driver by prohibiting cities from imposing or enforcing a minimum automobile parking requirement for residential and commercial projects under 40 units if the project is located within one-half mile walking distance of a major transit stop. The bill does not ban parking in areas near transit; rather, it allows builders the flexibility to balance parking with cost, providing an option to reduce parking—and therefore, cost—when feasible.

Locally-imposed fees for new housing developments can be another significant cost driver for new homes. Our 2019 study of a handful of California cities found that average impact fees were $23,455 for a single-family home and $19,558 for a multifamily unit, which is almost three times the national average. AB 2186 (Grayson, 2022) would encourage cities and counties to waive or reduce impact fees for affordable rental and homeownership housing developments (defined as those projects that restrict at least 75 percent of their units to low- and moderate-income families) by having the state reimburse half the total amount of any fee reduction or waiver granted to housing developers.

The legislature would also build on its recent successes in promoting ADU production with the introduction of SB 897 (Wieckowski, 2022). The bill would streamline ADU production and prevent local governments from requiring expensive building materials as a requirement to build. For example, it would prevent local governments from constituting ADUs as a Group R occupancy classification, thus stopping local governments from requiring ADUs to be built with more expensive apartment-grade materials. It also prevents local governments from requiring costly sprinklers for a JADU in homes that are not required to have them. Among other things, the bill also establishes the right to build a two-story ADU in most places.

Finally, developers of affordable housing projects in California must often contend with state requirements to set aside a large reserve of funding to address the unlikely scenario that a project’s federal rental assistance contract is not renewed. These project-level reserves, which can range from a few hundred thousand to more than three million dollars, invariably sit idle in bank accounts and add significantly to the overall cost of development. Senate Bill 948 (Becker, 2022) would eliminate project-level transition reserves altogether in favor of a more cost-effective statewide “Pooled Transition Reserve Fund” that can be accessed by projects on a case-by-case basis in the event federal assistance is not renewed.

Reducing Time Delays

Another major cost driver is the time it takes to approve new housing and to receive building permits. Several bills this session aim to speed up this process, both on the front end when the project is going through entitlements and at the back end when the permit is issued. The most notable of these bills is by Assembly Housing Chair Wicks, who introduced AB 2011 (2022), which would streamline the approval process for new housing proposed throughout the state on land that is currently zoned for commercial use. Specifically, areas currently zoned for office, retail, and parking would allow by-right affordable housing, while market-rate housing would include a 15 percent affordable housing requirement. In one case, we found that by-right approvals can help decrease the amount of time to build housing by 30 percent. From a cost perspective, the by-right provisions of the bill may be most useful for projects in high-cost areas and for 100 percent affordable projects that may already be subject to some of the additional wage requirements. In other regions, added wage requirements may not outweigh cost savings from expedited approvals.

The time it takes projects to conduct environmental reviews, or respond to environment-related litigation, can also delay new housing and lead to higher costs. In this session, legislators have taken on this issue specifically on housing for students and educators. SB 886 (2022) would provide a statutory exemption from the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) for student or faculty housing projects built on University of California, California State University, and California Community College campuses. AB 2295 (Bloom, 2022)would create a pathway for by-right affordable housing production on land controlled by school districts throughout the state. As our work with UCLA’s cityLAB and UC Berkeley’s Center for Cities + Schools demonstrates, there is tremendous potential to build affordable housing for teachers and school employees on excess and underutilized land.

Finally, even after receiving approvals, many projects still face unclear and complicated permitting rules and timelines and can spend months or even years waiting for building permit approvals. Assembly Bill 2234 (Rivas, 2022) addresses this issue by requiring local governments to approve or deny various building permits within a timeline: 30 days for small housing projects with 25 or fewer units and within 60 days for large projects with 26 or more units. If city staff cannot meet the post-entitlement permitting deadlines, local jurisdictions would have a no-cost option to contract with 3rd party permit reviewers to reduce the time needed to complete post-entitlement permits. In addition, the bill would require local jurisdictions to post templates of model permit applications and a checklist of required information for potential developers.

Conclusion

Policymakers should carefully examine issues related to major hard cost drivers. Continuing to assess the reasonableness and sizing of impact and permitting fees that are demanded of new housing construction and ensuring more projects can access by-right pathways for approvals is one pathway to reducing costs. Another is looking critically at the complexity of California’s Residential Building Code, including examining alternative code structures for differing development types (one model might be Oregon’s small home code).

The state should also find ways to promote and scale innovative construction methods such as off-site construction and mass timber. Our work has shown that off-site construction—and volumetric modular in particular—can help reduce construction time by 20-30 percent and help reduce total development costs by 5-20 percent. The state could also clarify, improve, and expand its scope and procedures for factory-built housing inspection, connecting more closely with local jurisdictions’ planning and building departments. Assemblymember Grayson has introduced two bills focused on off-site housing construction, AB 1056 and AB 2492, to help the state invest directly in the facilitation of innovative construction methods and assist the newly-established industry at large. However, the bills haven’t made it to the later legislative cycle. As for mass timber, Oregon updated its state building codes to allow the adoption of mass timber methods for 8-story buildings, respectively reducing construction time by up to 20 percent with additional cost reductions. International building code allows for up to 18 stories built with mass timber, which California could adopt and standardize in order to to reduce the cost of materials.

California has made significant progress over the last several years in opening up more zoned land for higher density housing, holding cities more accountable for effective planning, and providing funds for new affordable housing. But without meaningfully tackling the “hard cost” expenditure to build housing, lower housing prices are not likely to occur for a long time.