Steps Local Governments Can Take to Unlock More Housing: Lessons from San Diego

Published On October 8, 2025

Author: William Fulton, Terner Center Fellow

Co-authors: Sarah Karlinsky, Director of Research and Policy;

Quinn Underriner, Senior Data Scientist

Over the past few years, as the State of California has moved to push local governments to allow more housing and make it easier and quicker for developers to get that housing approved, the City of San Diego has moved even more aggressively in pursuit of the same goals.

During this time, San Diego has reformed both its planning policies and its permitting processes so that housing moves through the system much more quickly and with greater certainty as to the ultimate outcome. The reforms to San Diego’s planning policies are especially notable because the City has streamlined the process of updating Community Plans, which in the past had dragged on for many years, and has converted many project approvals from discretionary to ministerial. This transition is particularly important because ministerial approvals are not subject to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA), which has been frequently identified as a major contributor to the time and cost of approvals.[1]

While not all cities in California have the same staff capacity to execute the level of reform that San Diego has undertaken, the San Diego story contains important lessons that other cities can learn from in taking a more pro-housing approach.

Background on San Diego

With 1.4 million residents, San Diego is the second-largest city in the state by population and at 372 square miles, it is also geographically expansive, including coastal and inland areas, as well as high-density urban districts and low-density suburban neighborhoods.

San Diego is somewhat unique among California cities because neighborhood- and district-level land use is mainly governed by 50 Community Plans, which are essentially small area sub-plans tiered off of the City’s General Plan,[2] a document that guides local growth. The majority of critical details, such as neighborhood-level land use density, resides in these Community Plans rather than in the General Plan itself.[3]

Traditionally, each Community Plan area has had a community planning group that has played a formal role in the process, reviewing projects and providing advisory recommendations to the City’s planning commission. This process has been lengthy and cumbersome and has sometimes resulted in Community Plans that do not encourage increased density around transit. However that system of community planning has recently changed, as we describe below, though not all Community Plans have been updated.

Finally, San Diego divides its land use planning and land use permitting function between two departments: the Planning Department, which prepares land use plans and policies (sometimes called “long-range planning”), and the Development Services Department, which implements those plans and policies and issues discretionary entitlements and building permits.

This structure, which has been in place for decades, has recently facilitated San Diego’s effort to undertake two different types of changes to pursue a more pro-housing approach: plan-level changes in the Planning Department, and changes in the permitting process in the Development Services Department. We describe both in further detail below.

Plan-Level Changes

San Diego has pursued plan-level changes in two ways. First, the City has reformed the way it prepares Community Plans and approves projects that conform with those plans. And second, the City has also instituted a series of other pro-housing bonus policies separate from the Community Plans.

San Diego adopted its last comprehensive General Plan Update in 2008.[4] Although this plan called for increased density and concentrated development in certain locations, such as around transit stations, the specific details of these density increases were deferred to future Community Plan updates, which themselves stalled in the years following the General Plan Update.

In 2024 the City adopted a significant update to the General Plan known as Blueprint San Diego (or Blueprint SD).[5] The City also undertook a complete Environmental Impact Report (EIR) consisting of more than 2,000 pages for the Blueprint, which included an environmental review of two key Community Plans.[6] Although most of the City’s 50 Community Plans have not been updated recently, future Community Plan updates will be able to tier off the Blueprint EIR and will not need to complete their own EIR, expediting the update process.

Blueprint San Diego complements streamlining from revisions to the Community Plan process. First, if an individual project conforms to an updated Community Plan and the accompanying zoning, it is now approved ministerially. Such projects are no longer subject to a discretionary review process, meaning there is no analysis under CEQA and no review and approval by the San Diego City Planning Commission.

Second, projects are no longer required to be heard before the relevant community planning group. Previously, developers first had to have their plans reviewed by these neighborhood advisory bodies before they could be approved by the planning commission. Under the new system, community planning group review is optional, not required for ministerial projects. Instead, projects only need to be reviewed and approved by City staff.

There are exceptions to the ministerial approval process. If a project is close to wildlife habitat, an historic resource, or San Diego International Airport, it will likely be subject to discretionary review. The City Council is currently considering revising its approach to historic resources that would likely reduce the number of discretionary processes—for example, eliminating automatic review of any project that would disrupt buildings more than 45 years old—which would facilitate new development on property with existing buildings.

As a result of these collective changes, the number of permits issued ministerially has increased dramatically as Figure 5 shows below. Permit expediters in San Diego report that their job has fundamentally changed. Instead of shepherding a project through a complicated and highly political discretionary review process, they now typically spend their time working with their clients to shape the project in such a way that it can be approved ministerially.

Bonus Programs

At the same time that San Diego revised its system of creating Community Plans and ministerially approving projects that conform to them, the City also undertook a different pro-housing effort involving density bonuses near transit stations, as well as other steps to encourage higher-density housing near transit. Because developers have the option of using state density bonus law or local ordinances, there are two paths available for building beyond what is formally allowed under the zoning code.

At first, the City relied on Transit Priority Areas (TPAs)—areas within one-half mile from a major transit stop, which under state law qualify a project as eligible for a State-defined density bonus.[7] Such density bonuses allow developers to build more housing units than are allowed under local zoning in exchange for creating affordable units. In the TPAs, developers could access a local density bonus that exceeds the State options in exchange for providing certain levels of affordability.

In 2020 the City created a new bonus program, Complete Communities Housing Solutions. It permits housing bonuses above those allowed under state density bonus law, but in the form of increased floor area ratio (FAR), rather than additional housing units, if projects include a certain number of affordable housing units. These bonuses are available in areas zoned for medium- to high-density within Sustainable Development Areas. However, Sustainable Development Areas are more expansive than the Housing Solutions Areas. They are areas located within one mile (via a usable pedestrian path) of a major transit stop.[8] Projects in Sustainable Development Areas also qualify for streamlining and other benefits, even if they are not located in an area covered by a FAR bonus, as described below.

Developers still have the option of using TPAs if they want to take advantage of state laws such as Assembly Bill 2011 or Senate Bill 6, which provide ministerial approval for a project consisting mostly of housing on commercial land close to a transit stop.

Figure 1: San Diego Sustainable Development Areas

Source: City of San Diego Sustainable Development Area

The level of FAR bonus granted under Complete Communities Housing Solutions varies by FAR tiers. The tiers are based on factors such as average vehicle miles traveled (VMT), employment center proximity, and planned growth in Community Plan updates. In the areas with the lowest VMT and highest proximity to jobs, unlimited FAR is allowed. Subsequent tiers of density are indicated in the Complete Communities map below.

The City prepared a Program EIR for Complete Communities that streamlines approvals and eliminates the need for project-specific CEQA review for qualifying projects in low-VMT areas with good transit. In practice, this allows projects in places like Downtown San Diego—already designated as low-VMT—to pursue high densities and heights using a combination of the incentives without separate VMT mitigation. And, of course, if a project conforms to the Downtown Community Plan, it qualifies for ministerial approval in most cases.

Figure 2: San Diego Complete Communities Housing Solutions Map

Source: City of San Diego Complete Communities Initiative

Perhaps the most widely publicized planning program in San Diego has been the ADU Bonus Program, which allows multiple accessory dwelling units (ADUs) on a residentially zoned property in a Sustainable Development Area.

ADUs have been the subject of significant state legislation in the last few years. Since ADU approval was made ministerial by state law in 2017, there has been an explosion of ADU construction.

San Diego’s bonus program, adopted in 2020, goes much further than state law. It permits multiple ADUs on a property so long as half of those ADUs (technically, every other ADU added) is deed-restricted to low- and moderate-income families. The actual number of ADUs was initially unlimited, with the only constraints being setback, height, and FAR restrictions on the relevant parcel.

The City Council recently changed the ADU Bonus ordinance because of pushback from residents of neighborhoods with large (up to one-half acre) residential lots, which could potentially accommodate dozens of ADUs. Under the revised ordinance, ADUS are limited to between four and six units per parcel. However, developers whose applications were deemed complete prior to these recent changes can still move forward with a much larger number of ADUs under the old system.

Changes to the Permitting Process

At the same time the City has moved environmental review and other processes up to the plan level and converted many previously discretionary projects to ministerial review, it has also reformed and sought to expedite permitting processes in the Development Services Department (DSD), which is responsible for discretionary entitlements and building permits. This reform has greatly expedited development permitting.

Perhaps most importantly, Mayor Todd Gloria has issued two executive orders designed to expedite projects.

In January 2023, he issued Executive Order 2023-1, which directed all City departments to issue approvals (or requests for corrections) for 100 percent affordable projects within 30 days after a project application has been deemed complete. Building permits and Certificates of Occupancy must be issued within five days of approval of all underlying permits (such as electrical, mechanical, and fire) for both 100 percent affordable projects and shelters.

In January 2024, Mayor Gloria issued Executive Order 2024-1, which directed City departments to use the same expedited time frame for all Complete Communities applications, including for both market rate and affordable housing.

DSD increased its workforce from approximately 500 to more than 700 employees to comply with these Executive Orders and further expedite permitting processes in the City. Managers were given greater authority to monitor and shift workloads among staff so that no single employee would be overloaded. DSD also implemented a number of procedural changes designed to expedite permitting. These changes include the following:

- Applicants are assigned a dedicated project manager (called a Development Project Manager) within DSD to shepherd their project.

- DSD has created processes to determine quickly whether a project is eligible for expedited review and whether the application is complete.

- Perhaps most significantly, the Development Project Manager organizes meetings with the applicant that include representatives from almost all City departments, who are empowered to make decisions about the application on behalf of their department. These managers are charged by DSD with pushing hard to ensure that ministerial projects are processed quickly. DSD reports that, for the most part, these representatives of other City departments are embedded inside DSD and therefore able to make expeditious decisions.

Interestingly, DSD also makes clear in its guidance to applicants that they too must take steps to facilitate this expedited review. For example, at the front-end “eligibility meeting,” DSD’s guidance says the applicant must “help DSD prepare for expeditious processing, including whether the project will have any factors that may affect the complexity of the project and thus the effort, expertise, or time required for the review, such as whether the site contains existing buildings, what type of construction is being proposed, and whether the project intends to rely on phased occupancy or achieve compliance through the use of alternate methods or materials.”

Results

Like many California cities, San Diego now has an ambitious target under the State’s Regional Housing Needs Allocation program (108,000 units in the 2021 – 2029 period, or about 13,500 units per year) and is falling short of permitting those targets. However, there is some indication that San Diego’s program reforms are beginning to show results.

In 2023, the year after Complete Communities was expanded to include Sustainable Development Areas and the first year of Mayor Gloria’s Executive Order expediting 100 percent affordable projects, permits increased to nearly 10,000 units. In 2024, the City permitted almost 9,000 units, including about 1,000 affordable units.

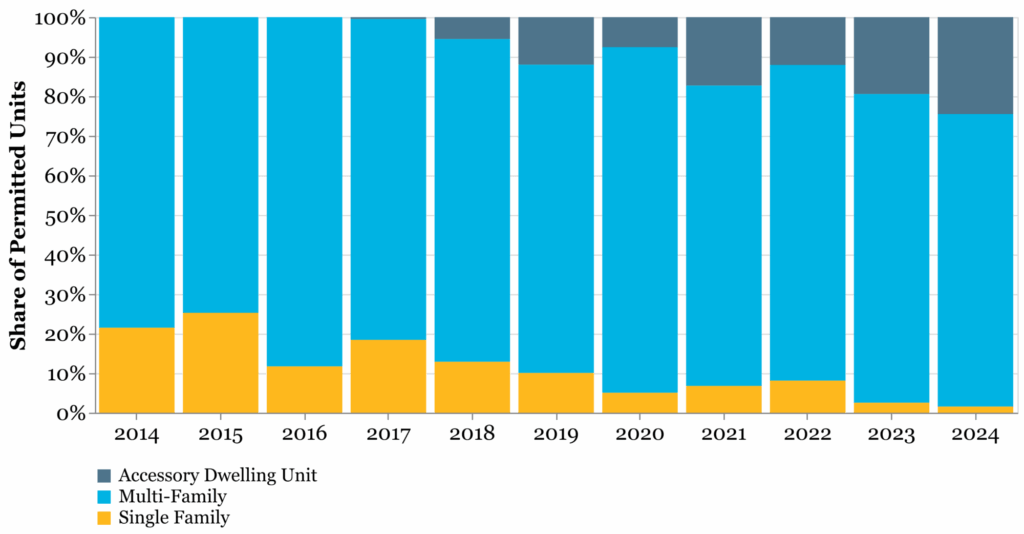

Between 2016 and 2024, new housing permits issued in San Diego have been overwhelmingly multifamily development and ADUs. Between 2016 and 2024, the total number of single-family units permitted declined from 864 to 132.[9] At the same time, the total number of permits for ADUs increased substantially. In 2016, there were zero, and in 2024, 2,107 ADUs were permitted.

Figure 3: Total Permitted Units by Income Group, City of San Diego 2014-2024

Source: City of San Diego Annual Progress Report

Source: City of San Diego Annual Progress Report

Figure 4: Permitted Unit Type as a Percent of Total Units, City of San Diego 2014-2024

Source: City of San Diego Annual Progress Report

Source: City of San Diego Annual Progress Report

Interestingly, while the number of discretionary permits issued by DSD has not changed appreciably, the number of ministerial permits approved has increased substantially over the last two years. In 2022, the number of ministerial permits was 5,314. In 2023, it was 9,693, and in 2024 it was 8,775.

Figure 5: Total Permitted Units by Permitting Process Type, City of San Diego 2022-2024

Source: Data obtained by the Terner Center for Housing Innovation from the City of San Diego Development Services Department

Source: Data obtained by the Terner Center for Housing Innovation from the City of San Diego Development Services Department

Conclusion

Obviously, some components of San Diego’s effort are hard for other cities in California to match. For example, few cities can add 200 permitting specialists in order to move things along. Nevertheless, San Diego’s recent efforts do provide a roadmap for cities, including those that are much smaller, seeking to increase housing production and expedite housing projects:

- Move most CEQA analysis up to the plan level.

Critical to San Diego’s approach is to deemphasize project-level CEQA analysis. By preparing full Environmental Impact Reports for a Community or General Plan, further environmental analysis for individual projects can be limited or even eliminated, even if projects are not covered by the State’s new infill exemption. - Permit ministerial approval of projects that conform to plans.

If plans are updated with comprehensive CEQA analysis and objective design standards, there is little reason for discretionary review. Conforming projects should be approved ministerially. - Create local density bonus programs.

Local density bonuses can be crafted in a way to provide significantly more density than state law while also aligning with a local jurisdiction’s planning priorities. By creating attractive local density bonus programs, as San Diego did, a local government can encourage additional housing (and affordable housing) while maintaining some control over the location and type of housing being built. - Use dedicated project managers and all-department meetings to speed permitting along.

By creating dedicated relationship managers and empowering staff from all departments to make decisions on an accelerated timeframe via a mandatory interdepartmental review meeting, San Diego solves for a major process component of getting housing built..

Acknowledgments

Our thanks to the following individuals for their thoughtful review of this commentary: Ben Metcalf, Carolina Reid, Sheela Jivan, Mike Hansen, Heather Riley, and Brian Schoenfisch. Additional thanks to Elyse Lowe for her response to our questions to support this project.

This research does not represent the institutional views of the University of California, Berkeley, or of the Terner Center’s funders. Funders do not determine research findings or recommendations in the Terner Center’s research and policy reports.

Endnotes

[1] These changes were put into place prior to the recent changes to CEQA exempting infill projects from environmental analysis. However, the San Diego process is still favorable because projects have ministerial status, not just a CEQA exemption. In other cities, infill projects may be exempt from CEQA but could still be subject to discretionary review.

[2] A General Plan is a California city’s blueprint for future growth and development, often called “the Constitution for future development of a community.” All California cities and counties are required to adopt General Plans and keep them current. Community Plans (sometimes also known as Area Plans) are technically part of the General Plan.

[3] Among California cities, only Los Angeles has a similar system of Community Plans. See a map of Los Angeles’s plans.

[4] City of San Diego General Plan 2008. Retrieved from: https://www.sandiego.gov/sites/default/files/legacy/planning/genplan/pdf/generalplan/gpexecsummarymar2008.pdf

[5] City of San Diego. Blueprint SD. Retrieved from: https://www.sandiego.gov/blueprint-sd

[6] These two Community Plans were a focused update of the Uptown community planning area to cover the infill neighborhood of Hillcrest, and a full update of the University Community Plan area near the University of California, San Diego. Both neighborhoods were slated for significant upzoning.

[7] A major transit stop is defined as a rail or bus rapid transit stop or the intersection of two high-frequency bus lines, meaning bus lines that operate on 20-minute headways or less.

[8] In moving to the Sustainable Development Area maps, the City sought to switch from an “as the crow flies” measurement, which didn’t take account of possible barriers such as freeways and canyons, to a measurement that involved actual pedestrian pathways.

[9] Note that single-family attached units are mapped to multifamily in our counts.