Residential Impact Fees in California

Published On August 7, 2019

As California continues to grapple with the devastating effects of the housing crisis, more attention is being paid to the rising cost of building new homes. The median home value in California has almost reached $550,000,(1) reflecting both the limited supply of homes as well as the high cost of development. In some cases, the cost of building affordable housing in California has topped $600,000 per unit, or more.

Strapped for revenue, localities are increasingly turning to development fees to fund vital public services.

In an effort to uncover paths to lower the cost of housing, the Terner Center has conducted research into the different components of the cost of development, from construction costs to the fees charged by local agencies on new housing. These development fees help support vital local services to serve incoming residents, including schools, utilities, and transit, and even affordable housing projects. They are a normal part of doing business for developers across the country. Still, California’s fees are especially high, driven in part by restrictions around other sources of local revenue for public infrastructure. State-level policies like Proposition 13 (the 1978 constitutional amendment by ballot initiative which restricts property tax levels) and decreases in federal support for public projects have limited the ability of local governments to fund infrastructure, resulting in an increased reliance on alternative funding sources, including development fees on new housing. Indeed, up to a third of some California cities’ budgets are composed of development-related fees. (2) In our prior research on development fees, we found that charges in California can exceed $150,000 per unit, not including utility fees. Our interviews also surfaced that utility fees can pose the largest local expense but unfortunately, we were unable to estimate them without detailed development plans.

Our latest paper takes an in-depth look at one segment of development fees – those under the authority of the Mitigation Fee Act, often referred to as “impact fees.”

In 2017, the California legislature passed Assembly Bill 879 which required, among other things, that the Department of Housing and Community Development undertake a study examining “the reasonableness of local fees charged to new developments as defined by [the Mitigation Fee Act. And to] include findings and recommendations to […] substantially reduce fees for residential development.” The legislature’s mandate culminated in the Terner Center’s latest report: Residential Impact Fees in California: Current Practices and Policy Considerations to Improve Implementation of Fees Governed by the Mitigation Fee Act. This work examines the state of impact fees across California and lays out potential paths towards reform.

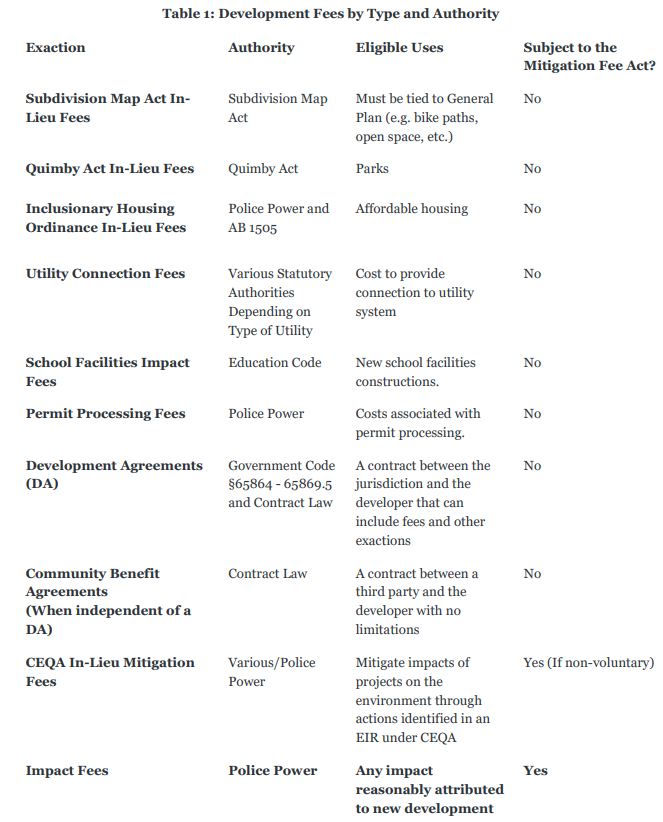

It is important to note that AB 879 restricted the scope of our research to just one segment of total development fees: those under the authority of the Mitigation Fee Act. These “impact fees” do not include school fees or utility fees, but they do include fees for other impacts directly related to new construction, such as some types of transit fees, park fees, and fees that fund affordable housing (Table 1).

The State could reform impact fees to guard against excessive costs through a number of avenues. But, first and foremost, greater transparency is needed.

We examine the methods by which cities develop and exact their impact fees, the actual amount that a sample of cities currently charge on new housing, and the general accessibility of this information. This research yielded several findings and considerations for improving fee design and implementation, all of which are detailed in our report.

Per AB 879, our report weighs a number of options for reform, each intended to promote a more thoughtful approach to the development and implementation of impact fees. Some of these reforms have clear utility and are straightforward to implement, such as policies that ensure that fee schedules and the studies that determine them are transparent and easily available to the public. Transparency and predictability in fee structure should be a common goal of all local agencies, because everyone should be able to quickly and easily assess the cost of building housing in their city.

Fees can also be better-structured to incentivize certain types of housing. For example, reducing fees on accessory dwelling units (ADUs) could encourage homeowners in invest in the small homes, adding density and supply in single-family neighborhoods.

Other potential reforms would adjust the structure of fees and the way in which they are set in an effort to make sure that they more appropriately reflect direct project impacts and do not inadvertently disincentivize housing construction. In our report, we do not recommend a single course of action, but rather weigh the costs and benefits of a set of potential reforms. The reforms considered take different approaches to lowering impact fees, including the following:

- Tightening oversight of how cities determine the relationship between a project and its impact on a community, as well as the connection between those impacts and fees charged.

- Creating stronger feasibility standards for determining what fee amounts could be reasonably absorbed by new developments.

- Improving other local funding options for infrastructure.

Our conversations with experts and stakeholders made it clear that some approaches would not be productive. Simply capping impact fees statewide, for example, could cut off much-needed revenue, resulting in lowered levels of public services and potentially incentivizing cash-strapped localities to block new housing altogether.

Policymakers will need to clarify their objectives and weigh the costs and benefits of different approaches before pursuing impact fee reform.

It is up to policymakers to consider each potential reform depending on their policy goals and priorities. For example, the state legislature needs to determine whether the intended result of any impact fee reform is to lower impact fees broadly, across the state, or to focus on reining in outlying fees that render new development infeasible.

As housing costs continue to rise, a comprehensive approach to impact fee reform is appropriate and necessary. Our report lays the groundwork for pursuing statewide reform to a key source of local revenue, but this level of reform deserves specialized attention to understand policy tradeoffs. The Governor has called for an impact fee task force, which would provide a forum for these detailed policy discussions. (3)

Policymakers should also consider reforms to lower the cost of development fees outside of the Mitigation Fee Act, and to ensure that localities can fund robust public infrastructure.

In addition, while our report focused on impact fees per AB 879, policymakers should also consider the universe of fees charged that are not regulated by the Mitigation Fee Act, as these fees also appear to be a significant contributor to overall costs. Indeed, an important first step would be bringing greater transparency and predictability to how all fees and exactions, taken together, affect the bottom line for new housing development.

Finally, this report does not delve deeply into the structural issues that constrain California cities and counties’ ability to raise revenue for critical infrastructure. This topic consistently came up in our interviews with stakeholders, and also merits a robust conversation. Ultimately, without significant property tax reform, cities and counties will continue to rely on alternative funding mechanisms such as impact fees to recoup the cost of maintaining and expanding residential services.

At a time of a tremendous need for housing, any policy that impacts the delivery of new homes must be examined in a thoughtful manner with an eye towards maximizing utility for all stakeholders. Our previous work has shown that high fees can be a barrier to new housing—both market-rate and affordable—and to the extent that cities are charging fees above what a specific market can support, everyone loses. Cities do not get the dollars to improve their infrastructure and maintain their services, and developers must secure more subsidy or charge higher prices in order to build. It is our hope that this new analysis will form the basis of a productive discussion that ultimately results in more homes for Californians.

(1) Zillow. “California Home Prices & Values”. Retrieved from https://www.zillow.com/ca/home-values/.

(2) Coleman, M. (Ed.). (2008). The California municipal revenue sources handbook (2008 ed). Sacramento, CA: League of California Cities.

(3) CalChannel. (2019, January 10). “Governor Gavin Newsom Releases 2019-20 State Budget” Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SrWC9XnKPKI.