A Plan to Keep Renters Housed Through the COVID-19 Recovery

Published On May 4, 2020

With unemployment resulting from the economic fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic soaring and the $484 billion stimulus package passed last week focusing solely on small businesses and hospitals, a looming housing crisis is coming ever larger into view. Despite the passage of the $2 trillion CARES Act, more significant and longer-term federal intervention is necessary to keep renters in their homes now and for the foreseeable future. We believe the best solution is federally-supported emergency rental assistance directly to those who need it: the millions of households who are unable to make rent due to job and income loss.

Recent Terner Center analysis shows that nearly 16.5 million renter households have at least one worker in an industry likely to be immediately affected by efforts to flatten the curve in the COVID-19 pandemic. There is no part of the country that will avoid this, as each state has its share of potentially-impacted renter households. Moreover, roughly 43 percent (or 7.1 million) of likely-impacted renter households were already struggling with rental cost burdens before the COVID-19 crisis took hold. It is clear that immediate and comprehensive action must be taken to assist these groups through what is poised to be the worst economic period in our nation’s history since the Great Depression.

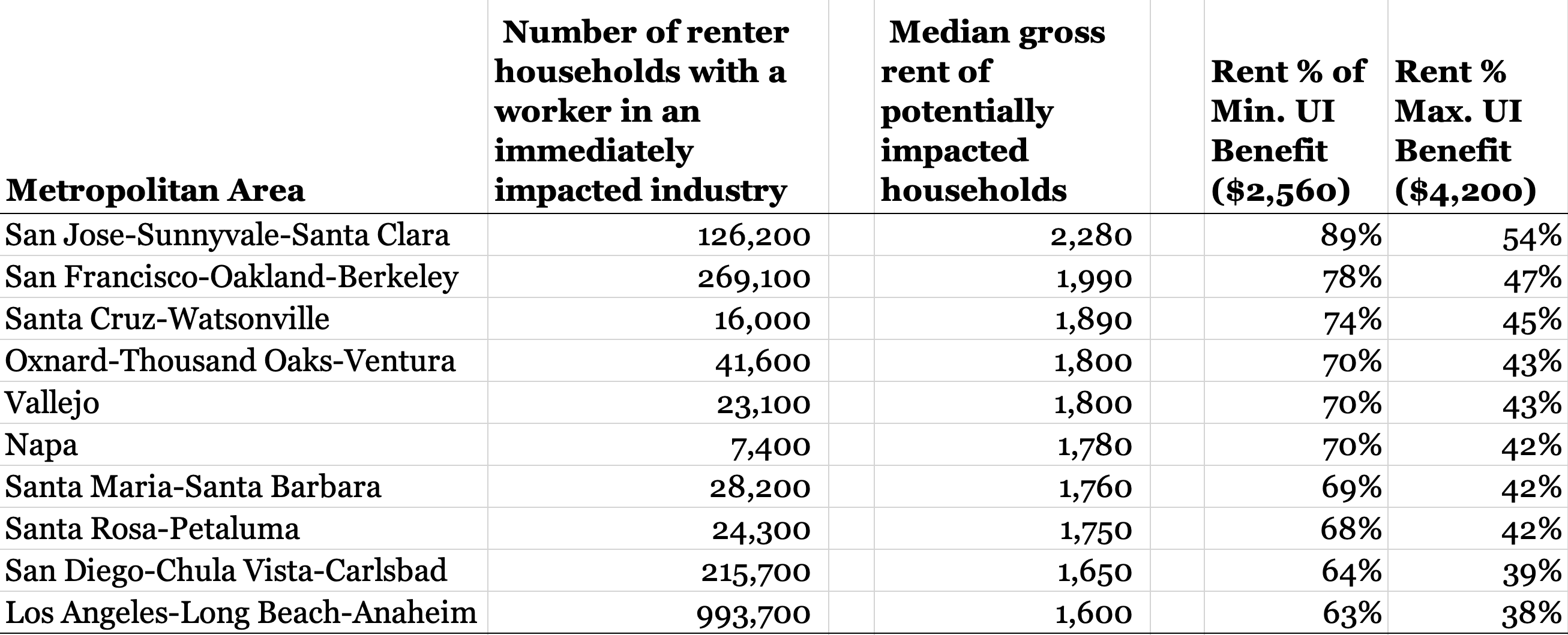

Despite significant attempts by policymakers at all levels of government to address the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic consequences, new aid and the mechanisms through which they are administered have been quickly overwhelmed by the sheer magnitude of this crisis. For example, expanded unemployment insurance through the federal CARES Act will be helpful to a degree, but will not be sufficient to address the rental assistance needed by many of the hardest hit households, particularly in expensive metro areas. For example, even if the nearly 270,000 immediately-impacted renter households in the San Francisco Bay Area receive the maximum unemployment insurance benefit, we expect that 47% of those benefits would go towards rent, far surpassing the 30% standard for being considered “rent-burdened.”

Table 1. Likely-Impacted Renter Households and Their Typical Rents Compared to UI Benefits, in Select California Metro Areas

Table 1 published originally in Estimating COVID-19’s Near-Term Impact on Renters. *Estimates derived from the 2018 American Community Survey microdata have been rounded.

Other local initiatives, such as eviction moratoria may be helpful in the short-term but do not address a tenant’s accrued rent due at the expiration of such moratoria. Ideas such as “rent forgiveness” ignore the debt service, payroll, and maintenance obligations of property owners, the majority of whom are small business owners. Simply forgiving rent for an extended period of time could also negatively impact pension funds—a substantial investor in multifamily housing—and chill future investment in new housing. As these types of existing short-term interventions expire this summer, a looming renter crisis awaits. In advance of that, Congress must take swift and decisive action.

Providing emergency rental assistance directly to those who need it

Following hurricanes Rita and Katrina and superstorm Sandy, the Disaster Housing Assistance Program (DHAP) provided emergency federal rental assistance to house displaced and unemployed families while regional economies slowly came back online. The DHAP program worked well in these instances because it was structured to phase out over a period of several years as tenants are able to resume paying rent as their income increases. Moreover, this program is built on the Section 8 voucher program, which leverages the capacity of local public housing agencies on the ground and has a track record of providing effective support to tenants, along with built-in protections (including against fraud) and oversight. A similar form of assistance should be deployed today to provide direct emergency rental assistance to households facing rental pressures as a result of the pandemic.

Using Section 8 vouchers to address an emergency response certainly has drawbacks, from inconsistent housing authority capacity to property owner reluctance to accept vouchers to regulatory requirements that complicate quick and efficient delivery (income verification, for example). But the voucher system is also the best federal program to deliver enough financial assistance to ensure that households remain stably housed during the pandemic and recovery. Moreover, the aforementioned challenges can be overcome. For example, project-basing some vouchers and easing or streamlining standard requirements such as unit inspections can ease overburdened housing authorities. As for the reservations of owners, the near-term loss of rental income should assuage fears about participating in the voucher program. Turning to vouchers in this moment could also be seen as an opportunity to modernize our country’s most widely-used housing assistance tool for the long term.

An infusion of rental vouchers, with a term of assistance sized to reflect a likely protracted downturn lasting three to five years, should be structured to:

Prioritize assistance for the most vulnerable renters. This emergency expansion could be structured as such: a first tier of priority for those who are experiencing homelessness and at most pronounced risk for COVID-19 in future waves of transmission; a second tier of priority for those low-income households who are currently housed but have been unable to pay any rent for an extended period and who have little to no verifiable income; and a third tier of priority for those very-low-income households who have become severely rent-burdened (i.e., they are paying more than half their current income in rent).

Allow landlords to apply for vouchers on behalf of their tenants. In instances where property owners house high concentrations of the populations prioritized for assistance, these owners should be allowed to contract directly with public housing authorities to secure Section 8 Project-Based Vouchers or directly with HUD through Section 8 Project-Based Rental Assistance for assistance for a portion of their units with qualifying tenants. This “project basing” is already a widely used tool among rental owners and has the benefit of reducing the paperwork burden for the renter households themselves and creating economies of scale for more capacity-constrained public housing agencies.

While we believe our proposal would provide significant and efficient protections to renters, other rental assistance mechanisms are also under consideration. Most notably a $100 billion forthcoming rental assistance proposal by the House Committee on Financial Services and Senator Sherrod Brown of Ohio which uses the Emergency Solutions Grant (ESG) program. ESG does not carry the same out year cost concerns of the Section 8 program and has a successful COVID-19 track record, having received $4 billion in the previously enacted CARES act. However, it should be noted that ESG has historically been used primarily as shallow short-term aid, which may not readily address the more severe and longer-term economic impacts that we face today. ESG, for example, has traditionally focused on serving formerly homeless individuals and is often administered through non-profit homeless service providers, many of whom do not have expertise in serving working families for longer periods of time. HOME, another program proposed as a vehicle for federal rental assistance, has similar capacity issues as a vehicle for aid to renter as its tenant-based rental assistance program is infrequently used by the cities who receive those federal funds and largely unfamiliar to property owners.

ESG and HOME have had significant success addressing key components of our housing crisis and are well-regarded by affordable housing providers and homeless service organizations. Ideally ESG and HOME would compliment a temporary renter voucher strategy as described in this policy proposal. Should Congress choose either of these programs as the primary vehicle for emergency rental assistance, significant changes in how each is administered must also be considered—as the pending legislation by Chairwoman Waters and Senator Brown is poised to do—including waiving local match requirements, providing flexibility on income levels served, and allowing direct administration by states where capacity does not exist at the local level.

Keeping tenants in place now

Regardless of which rental assistance program we rely on, we must understand that this process cannot happen overnight and we cannot afford to saddle renters with potentially devastating rent arrears that could quickly overwhelm any income they are able to regain after the crisis has ended. Moreover, not all renters will have access to tenant-specific rental assistance, nor expanded state unemployment benefits. Because of these issues, we also believe that property owners—most of whom are small businesses owners—must be able to access the credit they need to resolve short-term cash flow problems. As described in more detail in a recent article in Housing Wire co-authored by Terner Center Faculty Director Carol Galante and Barry Zigas of Consumer Federation of America, this can be accomplished through a loan program or federal guarantee available through existing multifamily lenders. These lenders could immediately offer loans to property owners that reflect rent roll losses incurred over a twelve to twenty-four month period. Loans would be required to be repaid in full and would be structured as subordinate deferred payment liens payable only at the time of future refinance or sale. In return for this assistance, property owners would be required to not move forward eviction proceedings during the term of the loan and concurrently waive any back-rent due from economically-impacted tenants. This approach keeps tenants in place until a robust rental assistance program can be deployed.

The last time we faced unemployment at the levels we’re experiencing today was the Great Depression, where widespread and persistent economic stagnation gave rise to many of the social safety nets that millions of people rely on today. From Social Security to mortgage insurance to the start of the nation’s public housing program, these foundational shifts in the federal government’s role built the backbone of the country’s economic growth in the 1950s and 60s. Today’s COVID-19 crisis similarly threatens to plunge us into unprecedented hardship, and as such, we should use this moment as an opportunity to reexamine some of the core principles of our social safety net and lay the groundwork for more transformational change. For now, the proposal we’ve laid out would extend relief to our nation’s renters in the near- and mid-term. But emerging from this crisis, a deeper, more innovative approach is needed to address the more systemic imbalances in our housing market, most notably the lack of access to federal rental assistance for low-income households and the profound dearth of new affordable and/or entry-level housing in high-opportunity communities. This crisis has revealed the deep fissures that were already present, and a return to business as usual housing structures would waste what may be a once-in-a-generation opportunity to reform our nation’s housing policy to ensure that all households can attain safe and stable homes.