Calibrating Policy to Ensure Success – An Analysis of Assembly Bill 1485

Published On April 9, 2019

The 2019 California legislative session has been a busy one for housing thus far. Dozens of bills have been introduced that aim in some way to alleviate the ongoing housing challenges across the state. It seems likely that this year’s package of housing bills could rival the 2017 housing package, depending on how upcoming committee hearings and negotiations progress. Some of the bills proposed so far could have significant impacts on our ability to build new housing. To this point, it is critically important to understand how to ensure new policies can achieve their goal of facilitating more housing development overall and, in particular, more housing that is affordable.

As part of our construction cost series, we have done work to educate advocates and policy-makers on the math behind development, with a particular focus on the importance of correctly calibrating policies to ensure success. One bill—Assembly Bill 1485 by Assemblymember Buffy Wicks—proposes local entitlement and California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA) streamlining incentives for Bay Area residential construction projects that pay prevailing wages and set aside 20% of base units for households making on average 120% of Area Median Income (AMI). To assess the potential impact of this bill, we adapted work that we have done previously estimating development feasibility for projects in the Bay Area to answer two specific questions: Would developers use this new tool? And can it achieve multiple, ambitious policy goals, including facilitating new development?

To begin to answer these questions, we layered AB 1485’s requirements onto our existing development prototype for the East Bay. This prototype (which we refer to as Terner Terrace) represents a common type of development project: a midrise (five to seven stories in height), market-rate rental project with ground floor retail. We also make a series of assumptions on our prototype regarding construction costs, local policies, fees, site conditions, and infrastructure requirements.

Terner Terrace

| Characteristics | Assumptions |

|---|---|

| 120 units (48 studios, 40 one-bedrooms, 32 two-bedrooms) | No demolition/significant site work required |

| 120 parking spots (1:1 ratio) | Normal entitlement timeframe |

| Five-over-one construction type (concrete podium + wood frame above) | $40,000 total development impact fees |

| 1,500sf ground floor retail | $65,000/unit land price |

From these prototype characteristics and assumptions, we created a financial analysis (known as a “pro forma”) to determine how likely it is that the project will actually get built.

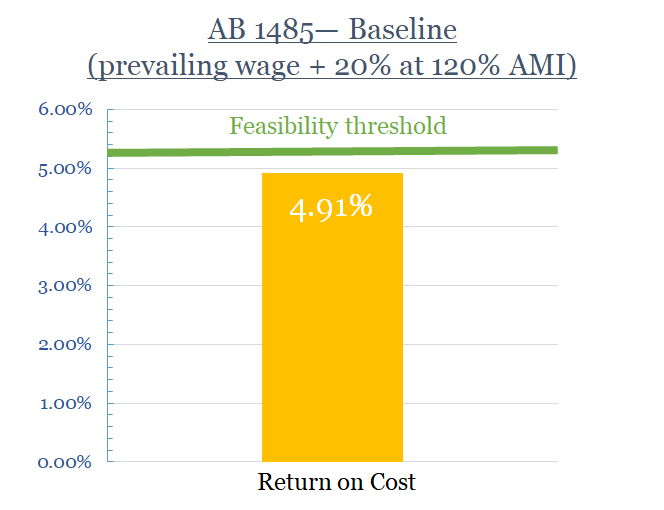

To assess the impact of AB 1485 on our prototype, we started by layering on the affordability and wage requirements first, without any of the proposed offsets provided by the bill. The results show that our prototype would have difficulty incorporating these provisions based on current market dynamics. As measured by a simple return on cost (ROC) metric (1), the prototype generates a 4.91% return. This would mean that the building would probably not get built, since on average, East Bay capitalization rates are about 4.25%, and financial partners will only invest in projects that generate a ROC at least one full percentage point higher than capitalization rates.(We go into more depth about why this is the case in an upcoming policy brief on development math.)

At baseline, it is unlikely that projects similar to the prototype would get built with these two specific requirements in the bill. While it is certainly worthwhile to pursue onsite affordability as well as stronger worker wages, the market dynamics are such that our particular project would not be able to include both and still achieve a threshold return.

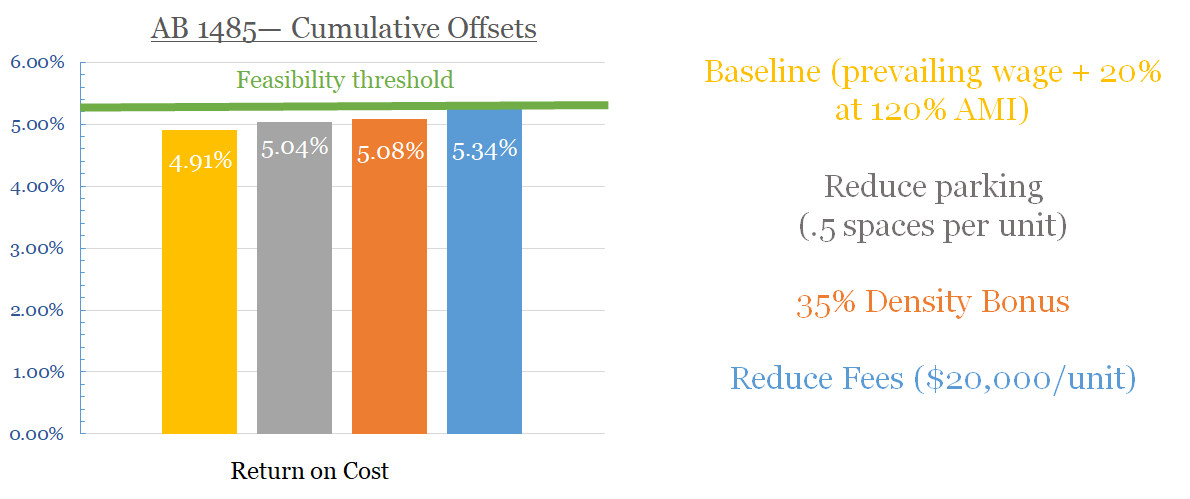

However, AB1485 also includes offsets to increase the value of development, including reduced parking, increased units, and reduced fees. When we include those provisions in the pro forma calculation, the project moves much closer to financial feasibility.

This points to an important dynamic in housing development: it is the confluence of a number of factors that determines project feasibility. By pairing cost reductions with prevailing wage and on-site affordability requirements, projects have a much higher likelihood of getting built and, therefore, achieving the desired policy goals of building more housing, incorporating affordability, and improving worker wages.

It is also important to note that market conditions greatly affect this cost calculus. The market rate rents needed to make this prototype project feasible are very high. As a result, these projects wouldn’t pencil in all neighborhoods.

Prototype rents required to achieve minimum ROC threshold

| Unit Type | Monthly Unit Rent | Per SF |

|---|---|---|

| Studio (375 sf) | $2,138 | $5.70 |

| 1 Bedroom (635 sf) | $3,366 | $5.30 |

| 2 Bedroom (935 sf) | $4,441 | $4.75 |

Moreover, the prototype assumptions do not include any costs associated with site remediation, infrastructure upgrades, or delays in entitlements or building permit issuance. It is not uncommon for projects to encounter these and other types of additional costs, which could significantly change project feasibility. The prototype was also based on a rental project, and a for-sale prototype would almost certainly be more costly given stricter insurance requirements and more expensive fixtures/on-site amenities (though, as currently drafted, AB 1485 affordable units would be allowed to rise to 150% of AMI on for-sale projects).

Given the variety of project types and diversity of local economic conditions in the Bay Area alone, there is no perfect approach to ensure policy success everywhere. That is why building flexibility into policies that impact housing development is of critical importance. AB 1485 attempts to address this by requiring developers to submit specific project information to localities so that they can assess the need for these incentives.

This analysis is neither an endorsement nor a critique of AB 1485. Rather, the analysis shows the importance of balancing policies to achieve the desired goals. Given increasing construction costs and limited availability of development opportunities, creating calibrated policies that consider diverse policy goals as well as market dynamics is critical to meeting the state’s housing production goals.

(1) Return on Cost is determined by dividing a project’s Year One Net Operating Income (revenue minus expenses) by total project cost.