In 2022, California Voters Will Vote Locally on Housing

Published On October 25, 2022

Voters in California have become accustomed to voting on big-ticket housing-related measures in general elections. In 2018, Californians voted to refill the state’s affordable housing coffers and turned back an effort to expand the state’s existing rent control parameters. In 2020, voters decided against raising taxes on commercial property—keeping the state’s Prop 13 intact—and again voted overwhelmingly to keep rent control laws as-is.

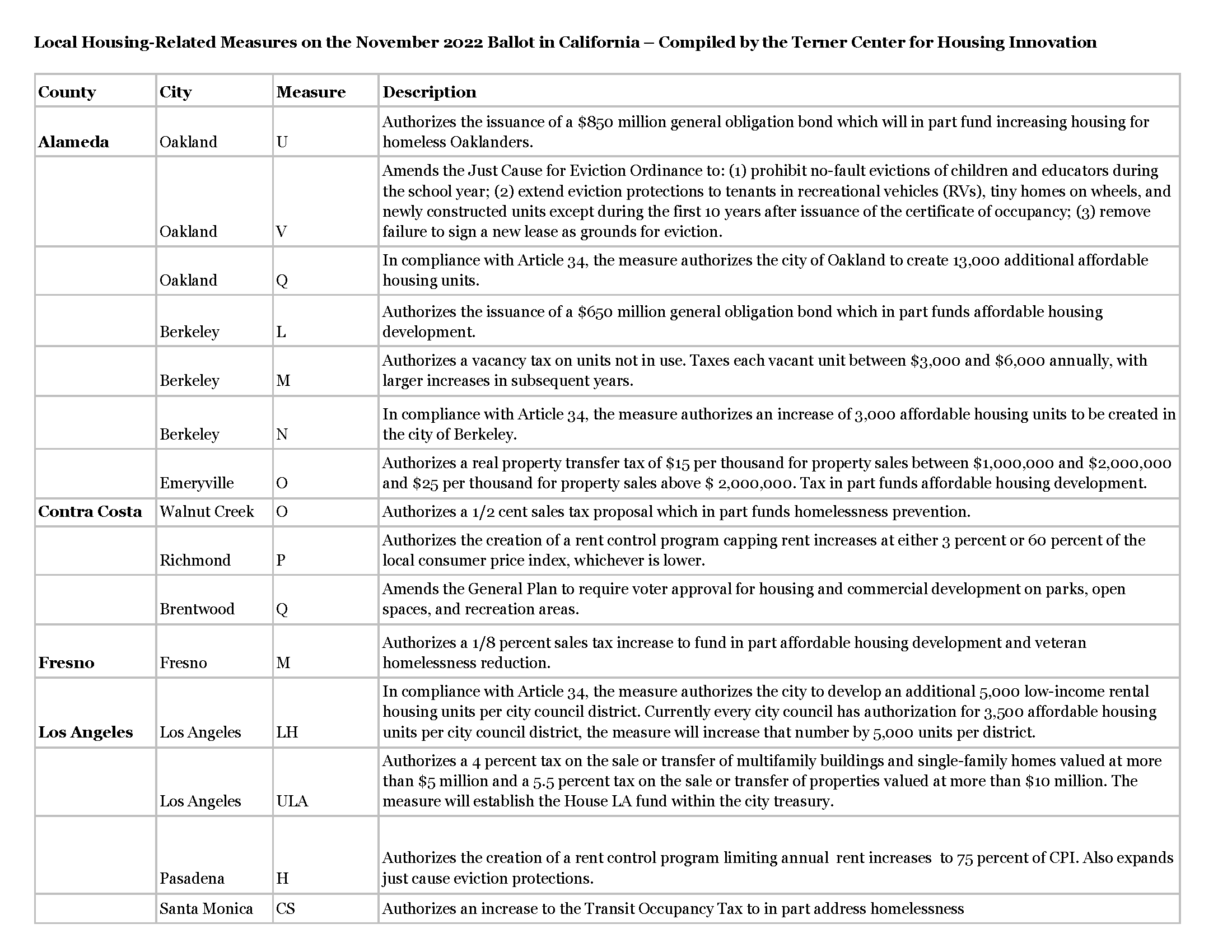

This year, voters in the November 8th general election won’t have a signature statewide housing proposition to consider. Instead, voters are more likely to face local choices regarding housing issues. In all, we counted 52 housing-related measures on local ballots across the state. The issues covered in these measures vary widely, including votes on changing local land use approvals, creating new sources of revenue for local housing initiatives, and establishing new or expanding existing tenant protection policies.

This commentary explores the themes we have observed in housing measures on the November ballot across the state. We also include a list of all such housing measures.

Changing housing approval and zoning rules

At least 16 measures will ask voters in cities across California to change how housing is approved at the local level. These measures mostly create or expand limits on how cities plan for and approve new housing, such as requiring public votes for zoning changes or project approvals. Some of these measures have been put on the ballot as a direct response to specific proposed housing developments that are opposed by some citizens. For example, in Menlo Park, Measure V was placed on the ballot in reaction to proposed housing for teachers and school staff on land owned by the East Palo Alto-based Ravenswood School District, which also serves a portion of Menlo Park. If passed, Measure V would require a public vote for any proposed variance to changes of a R1 (single-family-only) zoned neighborhood. The passage of the measure would effectively scuttle the teacher housing development from being built, and could complicate the City of Menlo Park’s plans to meet future state-mandated housing element requirements.

Similarly, in Santa Cruz, some residents have mobilized against a planned affordable housing development by placing Measure O on the ballot. The measure, if passed, would halt the construction of 124 affordable homes as well as a new city library on what is now a parking lot. In Laguna Beach, Measure Q would require voter approval for new housing in some areas, such as along Highway 1.

While outnumbered by measures that would inhibit new housing construction, a handful of measures seek to enhance pathways to homebuilding. In San Francisco, where the city is facing significant pressure from the state to find ways to increase housing production, voters placed Measure D on the ballot via signature collection. The measure would create a new mechanism to streamline housing production in exchange for affordability and labor requirements. In response to Measure D, the Board of Supervisors has placed a competing measure, Measure E, on the ballot that would create more modest streamlining in exchange for higher affordability targets (requiring 29.5 percent of new market-rate buildings be set aside for affordable housing compared to 25 percent for Measure D). In addition, Measure E projects could still be subject to discretionary review, meaning they could still be caught up in an elongated review process.

In Costa Mesa, voters are being asked to peel back parts of an earlier law (Measure Y, passed in 2016) that requires citywide votes to approve rezonings. Measure K would remove that requirement specifically for development along commercial corridors.

In San Diego, voters will once again vote on lifting the height limits around the Sports Arena redevelopment area, which is currently capped at 30 feet. Measure C is a redo of a 2020 voter-approved measure which was invalidated in court because of a technicality. The height limit increase would aim to allow more homes in a transit-rich neighborhood.

Finally, at least five measures ask voters to increase the number of new affordable homes that are allowed in those cities as required by Article 34, a rule passed in 1950 that requires local governments to hold an election for the construction, rehabilitation, or acquisition of affordable housing if government funds exceed 50 percent of the cost of a project. In 2024, a statewide repeal of Article 34 will be on the ballot.

Raising money for housing and homelessness prevention

Many cities continue to grapple with inadequate funding for affordable housing and services for people experiencing homelessness. As a result, there are several measures on the ballot across the state that would raise funds for these specific purposes. In a marked shift from past practice, several localities are explicitly including language regarding housing issues as part of sales tax renewals or increases. In all, there are at least 13 measures which mention affordable housing or homelessness as part of the measure’s description. Whether these revenues end up addressing these issues remains to be seen, as most sales tax measures would not restrict the use of new revenues as doing so requires a higher, two thirds vote threshold.

Taxing vacant units has emerged as one strategy for raising revenues to support affordable housing, particularly in the Bay Area. The cities of Berkeley (Measure M), Santa Cruz (Measure N), and San Francisco (Measure M) all have measures that would create fees on units that are held vacant, with some exceptions. These measures follow the implementation of similar ordinances in Oakland, California and Vancouver, Canada.

Some voters are being asked to approve other forms of taxes as well. In Los Angeles, Measure ULA would increase the transfer tax for multifamily buildings and single-family homes sold over $5 million and $10 million, respectively. The resulting revenue, estimated between $600 million and $1 billion, would be earmarked for the acquisition and construction of supportive housing. Similar transfer tax increases are also on the ballot in Emeryville (Measure O) and Santa Monica (Measure DT).

In East Palo Alto, Measure L would raise the gross receipts tax on property owners to fund affordable housing. In Oakland and Berkeley, voters will decide whether to authorize bonds to pay for affordable housing (Measures U and L, respectfully).

Expanding and creating new tenant protections

There are several local measures that would implement new tenant protections or make changes to existing ordinances. In Pasadena, voters will decide on Measure H, which would cap rent increases at 75 percent of inflation. The measure also includes the creation of a local just cause eviction ordinance to expand upon the protections created by the state’s AB 1482, passed in 2019. Just cause evictions would apply to all renters immediately upon tenancy (without the one year delay set in AB 1482) and are not set to expire in 2030. In Richmond, Measure P would limit annual rent increases to 3 percent of rent price or 60 percent of inflation, whichever is lower. Both ordinances would only apply to units built before 1995, and single-family homes would be exempt, as required by the state’s 1995 Costa-Hawkins rent control rules.

A few other cities are also making changes to their existing rent control ordinances. In Oakland, Measure V would prohibit no-fault evictions of children and educators during the school year and expand the City’s existing just cause eviction protections to residents of Recreational Vehicles and tiny homes. In Santa Monica, Measure RC would limit the applicability of the city’s existing owner-occupant evictions to owners who commit to move within 60 days of vacancy. And Measure EM also in Santa Monica would give the rent board authority to lower or eliminate previously approved allowable rent increases during states of emergency.

Click here for a table with all the 2022 local measures that our team has tracked.