Disparity in Departure: Los Angeles Region Supplement

Published On October 31, 2018

This study was published jointly by BuildZoom and the Terner Center for Housing Innovation at UC Berkeley.

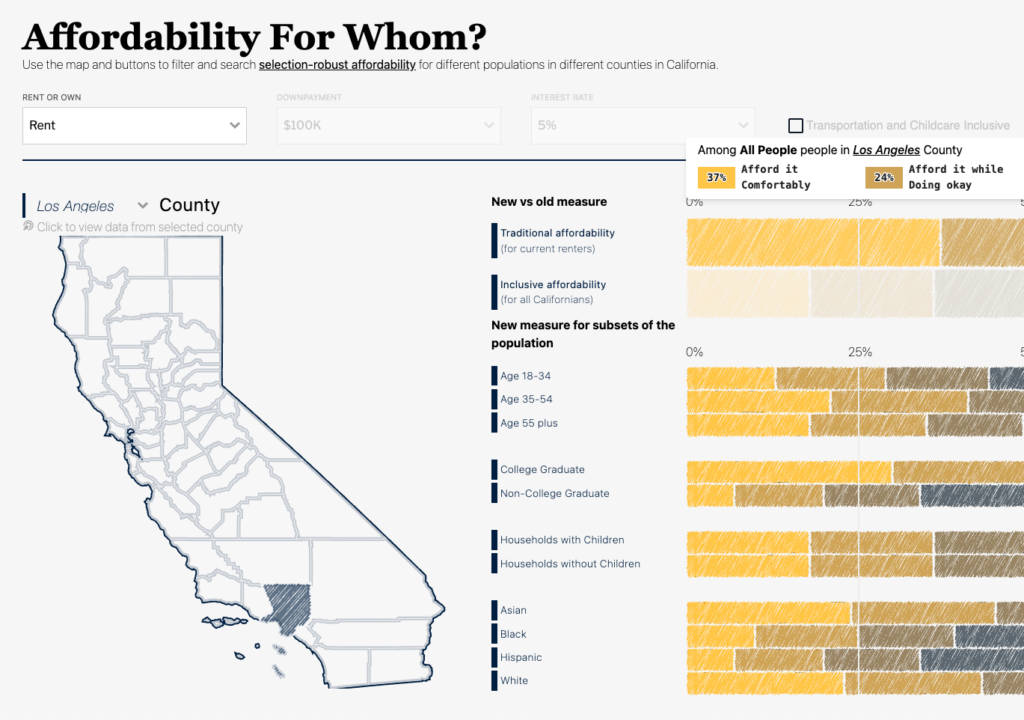

The Bay Area is undoubtedly at the forefront of a housing affordability crisis that is pricing a growing number of households—particularly lower-income households and households of color—out of the region. But it is not alone. Those same price pressures are apparent in other parts of the state (and country), including the Los Angeles region. While the two regions are different in many ways, they are similar in two key respects: both have powerful economies that have been drawing people in for a long time, and both have limited the supply of new housing for decades by preventing densification and—despite ongoing development in their far inland reaches—by slowing the pace of outward expansion as well. These factors are key drivers of the current crisis.

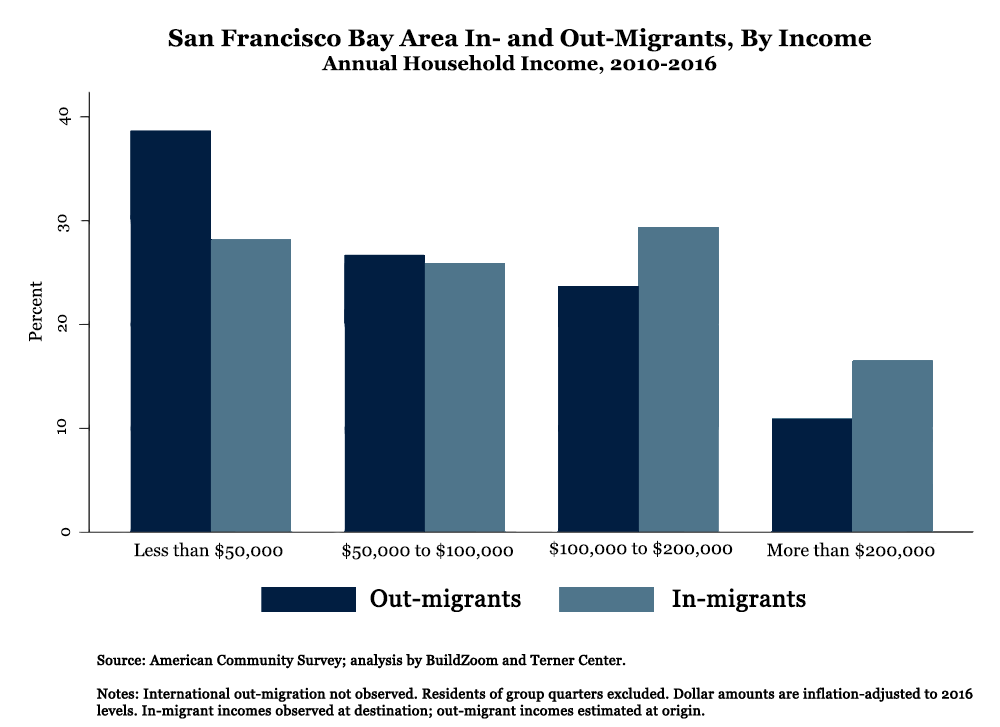

In a brief published earlier this month, we documented the tendencies of those leaving the San Francisco Bay Area to pursue different destinations depending on their income: high-income outmovers head to large metros around the nation, while low-income movers head to more affordable parts of California, such as the Sacramento region and the Central Valley. Below we apply the same lens to the Los Angeles region. (1)

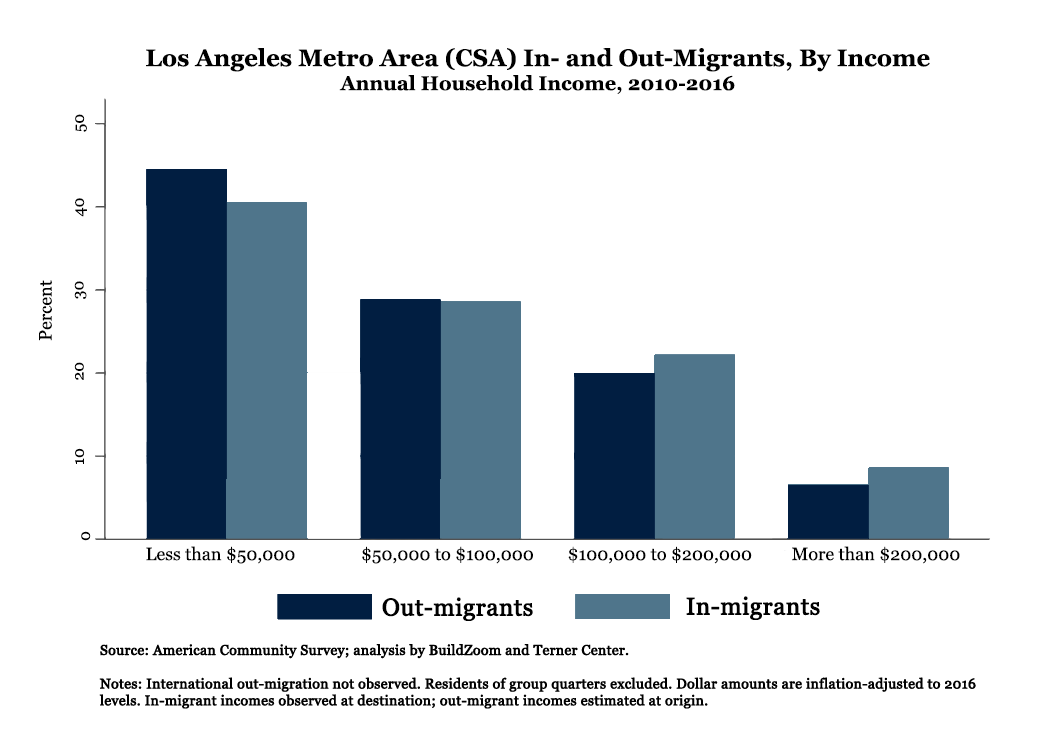

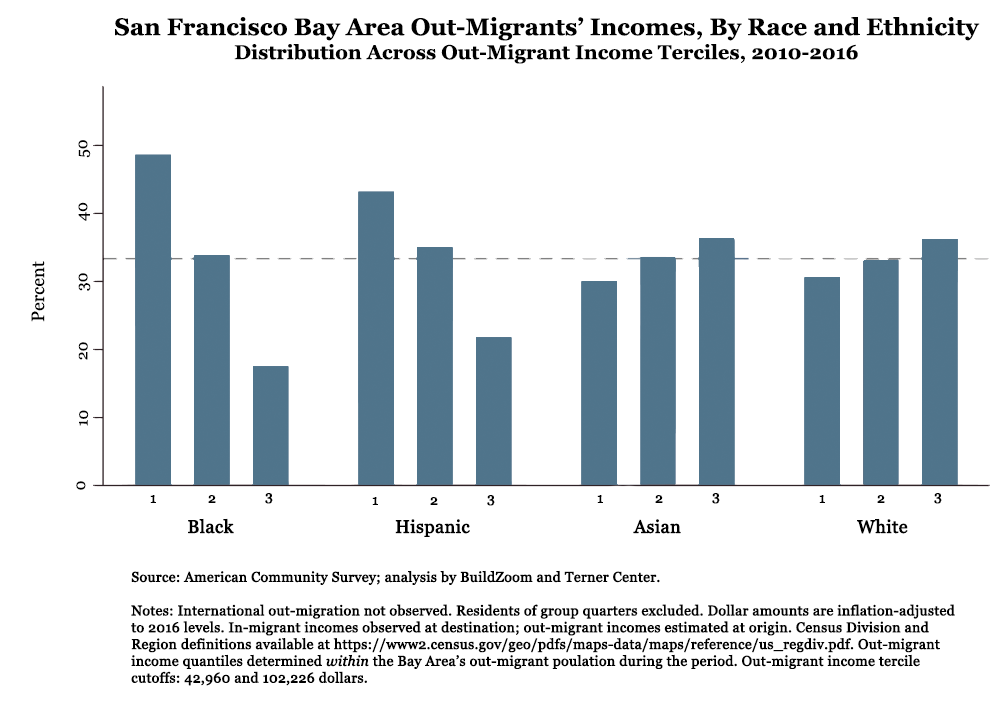

Similar to the Bay Area, the households leaving the Los Angeles region skew lower-income than the households moving in, although the disparities are less pronounced.

While the Bay Area is the epicenter of the global tech industry, the Los Angeles region’s economy is anchored in a wide range of more traditional industries, such as manufacturing and logistics. As a result, the Bay Area’s income distribution skews higher than the Los Angeles region’s, with the typical household earning over 40 percent more in the Bay Area (roughly $97,000 versus $68,000 in 2017, according to the American Community Survey).

The discrepancy between in- and out-migrant earnings that shows up in the Bay Area also emerges in the Los Angeles region, although to a more modest degree. Indeed, it is part of a broader national phenomenon of population sorting, whereby migration patterns increasingly concentrate the affluent in the expensive coastal cities while relegating the rest of the population elsewhere.(2)

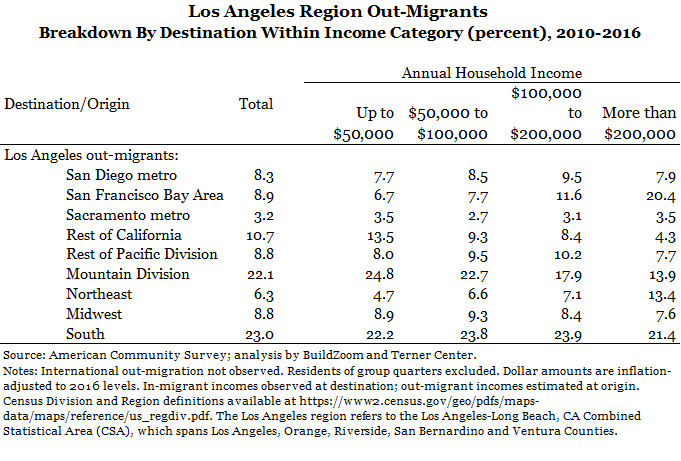

Roughly a third of the households leaving the Los Angeles region stay in California, and their destinations vary by income.

Similar to Bay Area out-migrants, the destinations of those leaving the Los Angeles region depend on their income. The San Diego and Sacramento regions appear to draw a similar share of outmovers in each income category, while those moving from the Los Angeles region to the Bay Area are disproportionately drawn from the highest income category: households with an annual household income of 200,000 dollars or more. In contrast, those moving to other parts of California (i.e. more affordable regions) are disproportionately drawn from the lower income categories. This situation mirrors that of outmovers from the Bay Area.

Download full breakdown of Los Angeles region out-migrant destinations and in-migrant origins

That said, compared to the Bay Area, there are fewer lower-income households overall remaining in California when they leave the LA region. Instead they tend to be going to more affordable regions in nearby states, like Las Vegas and Phoenix. Together, those metro areas account for more than half of the low-income movers to the Mountain Division, and appear to play a similar role with respect to the Los Angeles region that the Sacramento metro area does with respect to the Bay Area. These southwestern metros owe most of their growth to the economic strength of the Los Angeles region and its land use policy which fails to accommodate all those drawn there, prompting households to leave in search of more affordable markets.

Among the remaining U.S. destinations, those leaving the Los Angeles region for the Northeast were disproportionately drawn from the highest income categories, but those headed to other parts of the country were fairly evenly distributed across the income categories. A more nuanced result is that those moving to the San Diego metro area and to the rest of the Census’ Pacific Division—primarily the Seattle and Portland regions—were especially likely to be drawn from the second highest income category, with annual household incomes between 100,000 and 200,000 dollars. These destinations tend to be almost as expensive as the Los Angeles region itself, and are likely to attract higher earners.

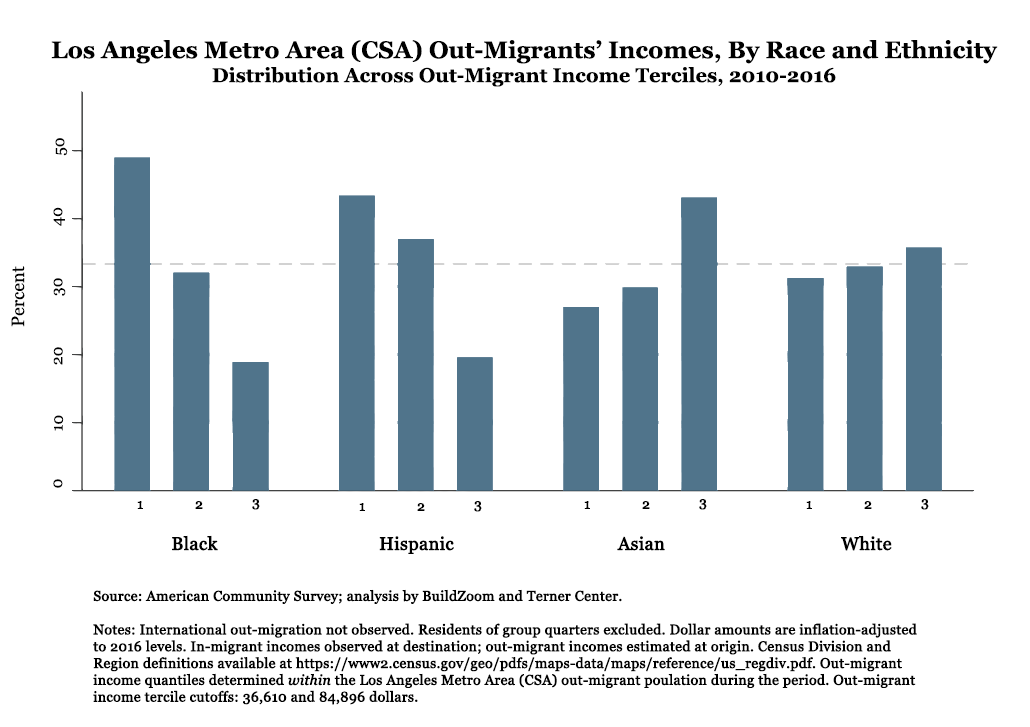

As in the Bay Area, Black and Hispanic households make up a disproportionate share of the Los Angeles Region’s low-income out-migrants.

The over-representation of black households among the Los Angeles region’s lowest-income out-movers mirrors patterns in the Bay Area, as does the disproportionate share of low-income Hispanic out-migrants. Just as in the Bay Area, the Los Angeles region’s black out-movers skew most heavily toward lower-incomes, followed by Hispanic out-migrants. But the Los Angeles region diverges from the Bay Area in the disproportionate share of high-income Asians leaving the region.

Hispanic movers leaving the Los Angeles region are more likely than blacks to stay in California, and are especially likely to move to the Central Valley, whereas blacks are slightly more likely to move to the Sacramento region. For those who leave California, Hispanics are more likely to move to the Phoenix and Las Vegas metro areas than blacks, although a substantial share of both move to these regions.

Conclusion

Even though the industries comprising the economies of the Los Angeles region and the San Francisco Bay Area are substantially different, as are the region’s income distributions, the destinations of those leaving them and the relationship between incomes and destinations have much in common. The expensive but opportunity-rich Bay Area and Northeast tend to be destination options for only the most affluent Los Angeles region outmovers, while those with less means find their way either to more affordable parts of California or to the Las Vegas and Phoenix metro areas, regions which, while certainly more affordable, may not offer greater access to opportunity.

As in the Bay Area, an essential step for addressing the Los Angeles region’s housing affordability crisis lies in building substantial amounts of new housing at all levels of affordability, within reasonable proximity to the economic opportunity at the heart of the region. Although the outward expansion of Los Angeles region is much slower than it used to be, it still continues to sprawl eastward. Such growth is so far-removed from the region’s core that its effect on housing prices is limited; the region needs not only to build more housing but to locate it strategically by densifying sought-after and opportunity-rich areas within the metro. And because reaching those production goals will take time, if the Los Angeles region is to stem the affordability pressures on low-income households and people of color in the near term, those goals should be paired with efforts to preserve existing affordable housing and strengthen protections against displacement for vulnerable residents.

Notes

(1) We define the Los Angeles region broadly—consistent with its official Combined Statistical Area—to span Los Angeles, Orange and Ventura Counties, as well as the so-called “Inland Empire” counties of Riverside and San Bernardino.

(2) As in the Bay Area analysis that aggregates Silicon Valley, San Francisco, and Stockton, this analysis does not capture substantial affordability-driven mobility within the Los Angeles region, and especially between the region’s core in the Los Angeles Basin and its still-growing eastern periphery in the so-called Inland Empire. The discrepancy between in- and out-mover incomes is more pronounced for the coastal counties of Los Angeles, Orange, and Ventura, whereas for the inland counties of Riverside and San Bernardino, it is negligible.

Data and Methodology

This study uses data from the American Community Survey, and in particular from the 1-year individual and household data from the years 2011 through 2016. For details regarding (i) the definition of metropolitan areas, (ii) the identification of migration, its timing and its origin and destination, and (iii) the determination of income levels at origin and destination, see methodology notes in the related study entitled “Characteristics of Domestic Cross-Metropolitan Migrants.”