Getting Vouchers to Households in Need: Learning from Hawaii’s Lease-in-Place Preference

Published On October 9, 2024

Author: Christi Economy

Introduction

The Housing Choice Voucher (HCV) program is one of the country’s most powerful tools for keeping people stably housed. Vouchers reduce housing instability and homelessness by covering rent and often utility expenses (up to a cap) for low-income households.1 However, there are not enough vouchers to meet the need: one in four eligible households receive a voucher or other type of rental assistance, often after spending years on waitlists.2 Even with a voucher, it can be difficult for households to find an eligible place to rent due to limited housing stock, rising rents, and landlord reluctance to rent to voucher holders. Nationally in 2019, only about 60 percent of households who received a voucher were able to successfully lease a housing unit within six months.3

During the Covid-19 pandemic, many households became increasingly rent-burdened and at risk of homelessness, and urgency mounted to keep people stably housed. In Hawaii, these challenges were exacerbated as the tourism industry shut down and many renters lost their jobs. The Hawaii Public Housing Authority (HPHA) mobilized its HCV resources to assist struggling renters, adding to a range of pandemic-response efforts that also included the Emergency Rental Assistance Program.4 The public health crisis worsened perennial difficulties leasing vouchers, however, because the process often requires several in-person interactions. In response, HPHA rolled out a program that gave preference to HCV applicants able to “lease in place,” meaning they would be able to use the voucher to pay for the unit they were already leasing.5 In the midst of a statewide eviction moratorium and broad nonpayment of rent due to COVID income losses, the housing authority saw this strategy as a potential win-win for tenants and landlords. Families would have the voucher to cover their rent and reduce ongoing cost burdens, and landlords would have a guaranteed rental income.

This piece summarizes HPHA’s lease-in-place (LIP) preference program and highlights five key lessons regarding the program’s effects on success rates, budget, administrative burden, and the potential fair housing concerns related to racial equity and mobility. It concludes with how lessons from HPHA’s LIP preference may be relevant in the post-pandemic era, particularly to overcome enduring challenges for leasing housing vouchers.

Hawaii’s Lease-in-Place Preference

In Fall 2020, HPHA rolled out an LIP preference for households that qualified for the HCV program and were already leasing from a landlord willing to participate. Typically, households issued a voucher try to find a new unit to rent, either because they want to move or their existing living situation would not be compatible with the voucher.6 Finding a new unit is difficult, however, due to limited available housing stock and landlord reluctance to participate in the program.7 Many families end up not being able to use their voucher.8

Voucher holders encountered more difficulty searching for housing during the pandemic, when public services became more challenging to administer and people were advised to stay in their homes. Through the LIP preference, HPHA was able to rapidly deploy their vouchers by targeting families who already had a unit and a willing landlord.

In October 2020, HPHA accepted HCV applications for the LIP preference over a five-day window. Approximately 6,000 families applied. Of these, 3,000 were eligible and HPHA received 900 complete applications. In December 2020, the initial LIP households—those that met the HCV program’s eligibility criteria and demonstrated they were able to lease in place—were accepted into the program. By the end of January 2021, approximately 800 new families were supported by vouchers through the preference program, accounting for about one-quarter of all of HPHA’s HCV participants.9

Much can be learned from Hawaii’s experience rolling out the LIP preference, including the five key lessons below:

The LIP preference helped sidestep common barriers to successfully using vouchers—the lack of available, affordable units and landlord reluctance—allowing the housing authority to serve a larger number of families.

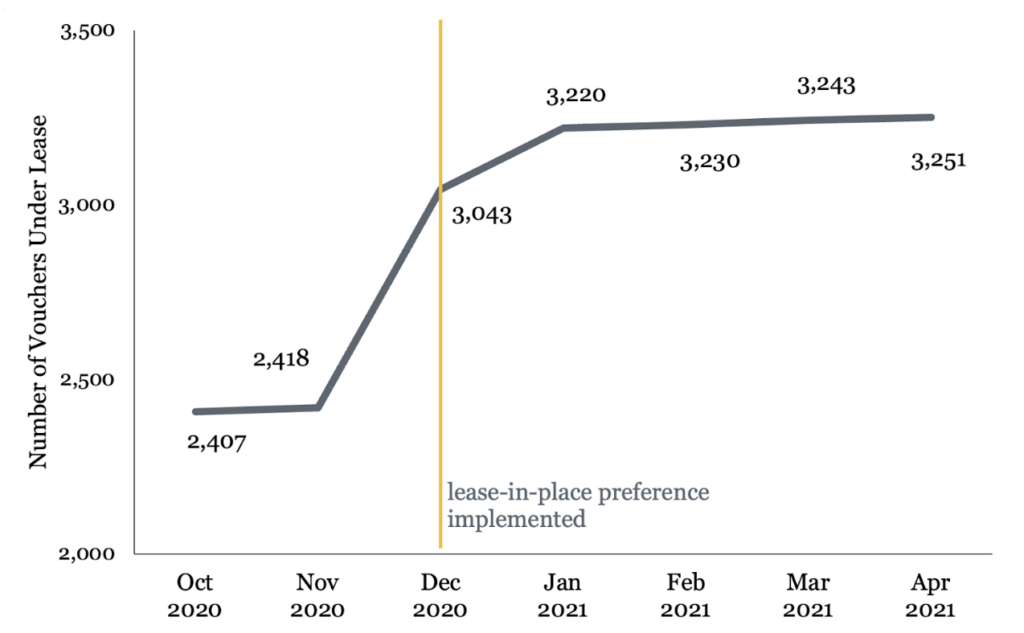

The LIP preference allowed HPHA to lease a large number of vouchers very quickly, adding over 800 new households to the HCV program in just two months (Figure 1). In contrast, the number of vouchers under lease nationally declined over this same time period.10 Because program participants did not have to find available units in the market and their current landlords had already agreed to participate, nearly all (about 90 percent) of the households admitted to the program were successfully able to use their voucher. This success rate was much higher than for the HCV program in general (about 60 percent nationally in 2019).11

Figure 1. Number of Leased Housing Choice Vouchers with the Hawaii Public Housing Authority, October 2020 to April 2021

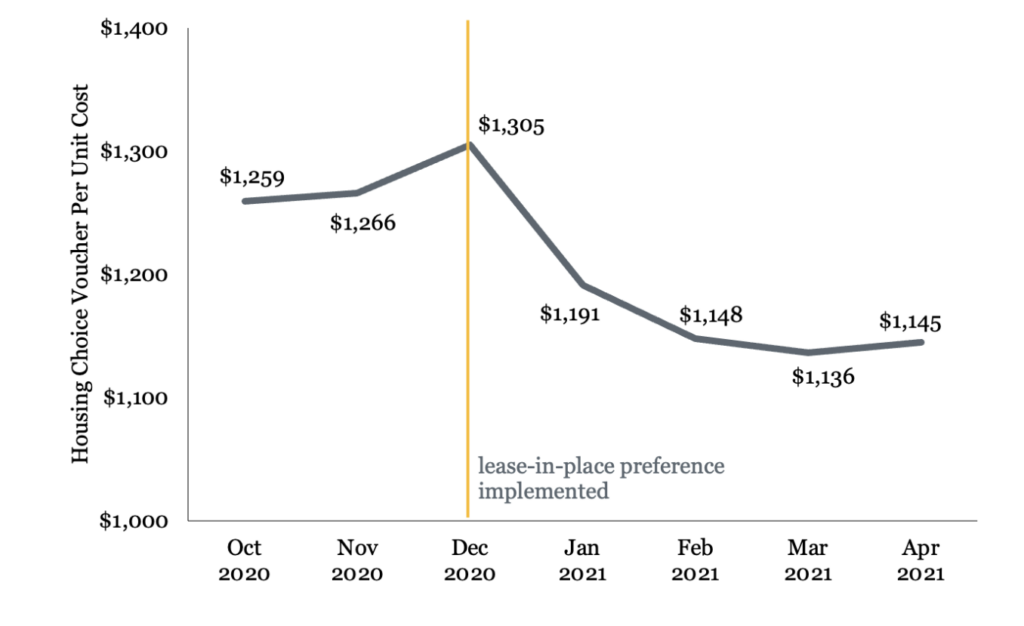

The high success rates pushed HPHA beyond its HCV budget authority, even though average costs per voucher decreased following the LIP preference.

Public housing agencies (PHAs) typically issue many more vouchers than they have the budget for, as they expect that many households will not be able to use their voucher successfully. With the LIP preference, more families than anticipated were ultimately successful in using their vouchers, and HPHA significantly exceeded its budget authority for this period. To cover their budget shortfall, HPHA received approximately $3 million in additional funding from the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).12 HUD had funding available in part due to a pandemic-related slowdown in voucher utilization nationwide. Funding to cover shortfalls in PHA budgets has become less accessible since then, because the number of leased vouchers has grown nationally and rising rents have increased the average cost of each voucher.13

Although HPHA’s expenses exceeded its budget overall, the average cost per voucher decreased by more than 10 percent following implementation of the LIP preference (Figure 2). This decline suggests the LIP participants tended to live in units with lower rents than voucher holders who needed to lease a new unit.14 This trend is consistent with rents among longer-term tenants being lower than current market rents. In 2021, the average monthly rent for very low-income households in Hawaii was about $450 lower for those who had lived in their unit for at least a year compared to those who moved in more recently.15 LIP participants, who found their current homes without voucher assistance, could also have selected less expensive units than participants who selected units with a voucher already in hand.

Figure 2. Average Per Unit Costs for Housing Choice Vouchers with the Hawaii Public Housing Authority, October 2020 to April 2021

The rapid issuance and high success rate for LIP vouchers required substantial administrative effort without a corresponding increase in staff capacity.

PHAs often do not receive enough administrative funding from HUD to fully cover the costs of the HCV program. Most HCV program costs go towards staffing, including time spent on eligibility certifications, voucher issuance, program intake, and inspections. Annually, PHAs spend about 6.8 hours per household performing tasks associated with maintaining ongoing occupancy, such as annual recertifications or processing moves.16,17,

In just two months, HPHA’s voucher program grew by one-third with an influx of over 800 new leased vouchers (Figure 1). This growth equates to an additional 5,440 hours per year (or nearly three full-time employees) to support the new households in the program. This expansion occurred without simultaneous increases in personnel, contributing to a greater administrative burden facing HPHA’s staff.

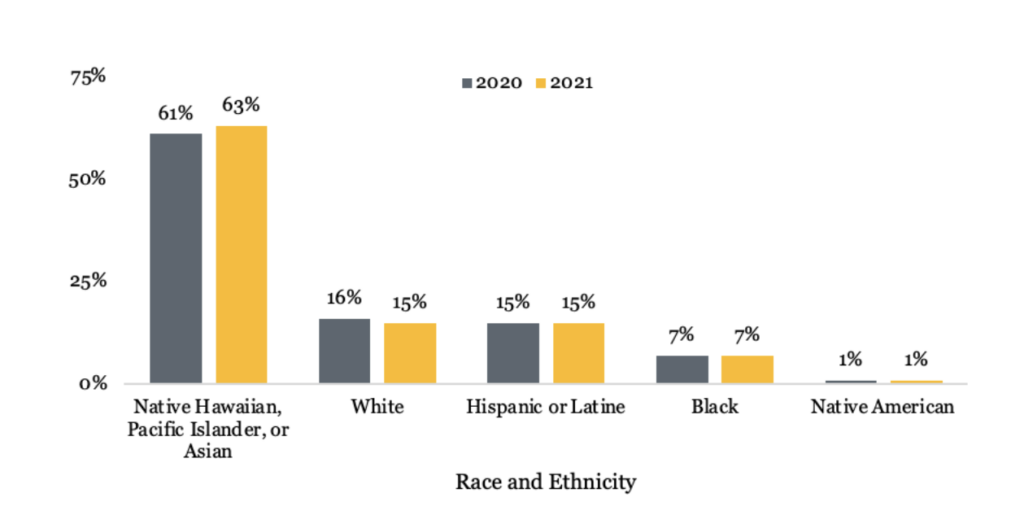

The racial and ethnic composition of HCV participants changed very little after implementing the LIP preference, mitigating a potential fair housing concern.

One potential concern with the LIP program was whether—by selecting households already living in a unit with a landlord willing to participate—it would violate fair housing laws by disproportionately serving people from a specific racial or ethnic group. HPHA conducted a fair housing analysis to check that the preference would not undermine their racial equity goals. Ultimately, the racial and ethnic composition of HPHA’s HCV participants was very similar before and after implementing the LIP preference (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The Racial/Ethnic Composition of Housing Choice Voucher Holders with the Hawaii Public Housing Authority, 2020 & 2021

Note: Hispanic/Latine includes people of all racial groups. All other categories are non-Hispanic/non-Latine.

The LIP preference did not lead to significant changes in the neighborhood conditions for HPHA’s voucher holders.

One aim of the HCV program is to provide neighborhood choice for tenants, opening up access to lower-poverty neighborhoods with high-quality schools, amenities, and employment opportunities. However, in reality, due in large part to limited affordable options, many voucher holders end up leasing in high-poverty neighborhoods.18 Even so, an LIP preference limits the choice of where to live for voucher participants, potentially undermining the ability for households to move to a neighborhood better suited to their needs. To mitigate this concern, participants in Hawaii’s LIP preference are allowed to use their voucher for a new unit after one year.

The data show little change in the characteristics of the average voucher holder before and after HPHA’s implementation of the LIP preference. The neighborhood poverty rate for the average voucher holder decreased slightly from 17 percent to 15 percent, as did the share of single-family homeowners (Figure 4). LIP households may also have benefited from increased housing stability. By remaining in place, households were not subjected to potential disruptions in school or employment access, existing social networks, or other connections to their community.

Figure 4. Neighborhood Characteristics for Housing Choice Voucher Holders with the Hawaii Public Housing Authority, 2020 & 2021

Note: Neighborhood characteristics are measured using the Census tracts where HCV participants live.

Conclusion

A lease-in-place preference is one potential tool for housing authorities to use their housing vouchers more quickly and effectively, particularly those with vouchers they struggle to use. Because so many people who need assistance are already renting, an effective lease-in-place option can make it easier for tight rental markets to absorb an expansion in voucher resources. In Hawaii’s context during the Covid-19 pandemic, the preference worked well to deploy resources rapidly to over 800 households in need. However, Hawaii’s experience points to many factors shaping whether an LIP preference fits the local context.

In Hawaii, the LIP preference yielded unprecedented success rates, but also had mixed effects on the budget and led to HPHA overshooting their budget authority. HPHA also had to design the program and assess fair housing concerns to ensure that the preference would not undermine their racial equity or mobility goals.

It is also important to consider who the LIP program leaves out. By definition, a lease-in-place preference will not target resources to people experiencing homelessness or living in unstable housing situations. These populations—who many would consider the most in need of support—are ineligible for a preference that relies on an existing housing arrangement with a willing landlord. During the pandemic, the Emergency Housing Voucher program was rolled out specifically to support the population experiencing or at risk of homelessness.19 Outside of this context, however, it is important to consider the tradeoffs of an LIP preference with providing vouchers to people experiencing homelessness.

Hawaii’s experience demonstrated the power of the LIP preference in sidestepping one of the biggest challenges with the voucher program—finding available units with willing landlords. Keeping in mind the tradeoffs and factors discussed above, other housing authorities may be able to learn from this approach.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Ophelia Basgal and Ryan Finnigan for their guidance and thoughtful contributions. The publication benefited from reviews by Terner Center colleagues: Carolina Reid, Sarah Karlinsky, and Ben Metcalf. Will Fischer, Tushar Gurjal, and Madeline Morris provided helpful external reviews. Thank you to Chansonette Buck, Geraldine Slevin, and Sheela Jivan for supporting the publication process.

We would like to thank Wells Fargo for supporting this research.

This research does not represent the institutional views of UC Berkeley or of the Terner Center’s funders. Funders do not determine research findings or recommendations in the Terner Center’s research and policy reports.

Endnotes

- Ellen, I.G. (2020). “What Do We Know about Housing Choice Vouchers?” Regional Science and Urban Economics, 80, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2018.07.003.

- Acosta, S. & Gartland, E. (2021). “Families Wait Years for Housing Vouchers Due to Inadequate Funding.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities. Retrieved from: https://www.cbpp.org/research/housing/families-wait-years-for-housing-vouchers-due-to-inadequate-funding.

- Ellen I.G., O’Regan, K., & Strochak, S. (2021). “Using HUD Administrative Data to Estimate Success Rates and Search Durations for New Voucher Recipients.” US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research. Retrieved from: https://www.huduser.gov/portal//portal/sites/default/files/pdf/Voucher-Success_Rates.pdf.

- Kneebone, E., & Underriner, Q. (2022). “An Uneven Housing Safety Net: Disparities in the Disbursement of Emergency Rental Assistance and the Role of Local Institutional Capacity.” Terner Center for Housing Innovation, UC Berkeley. Retrieved from: https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/research-and-policy/uneven-housing-safety-net-emergency-rental-assistance-and-local-institutional-capacity/.

- To receive the LIP preference, tenants had to meet the existing HCV eligibility criteria and be currently leasing from a landlord willing to participate in the program.

- Examples of an existing living situation not eligible for the LIP preference include people experiencing homelessness, living in unstable or unsafe conditions, or currently renting from a landlord unwilling to participate in the program.

- Landlords may be reluctant for a number of reasons, including source-of-income discrimination or concerns about the additional administrative burden of working with the housing authority. See: Cunningham, M., et.al. (2018). “A Pilot Study of Landlord Acceptance of Housing Choice Vouchers.” US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research. Retrieved from: https://www.huduser.gov/portal//portal/sites/default/files/pdf/ExecSumm-Landlord-Acceptance-of-Housing-Choice-Vouchers.pdf; and Garboden, P., et. al. (2018). “Taking Stock: What Drives Landlord Participation in the Housing Choice Voucher Program.” Housing Policy Debate, 28, no. 6: 979–1003, https://doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2018.1502202.

- Ellen, I.G., O’Regan, K., & Strochak, S. (2021).

- Hawaii Public Housing Authority. (2024). “Fiscal Year 2024–2025 Annual PHA Plan.” Retrieved from: https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/61d64d5f9d24da33de8c58ab/64bf0dceecc4ac461b278962_DRAFT_hi001v01_2023-2024%20Annual%20PHA%20Plan_50075-ST_1-19-23%20d3a.pdf.

- Housing Choice Voucher Data Dashboard. (2024). Department of Housing and Urban Development. Retrieved from: https://www.hud.gov/program_offices/public_indian_housing/programs/hcv/dashboard.

- Ellen, I.G., O’Regan, K., & Strochak, S. (2021).

- Hawaii Public Housing Authority. (2021). “Fiscal Year 2021–2022 Annual PHA Plan.” Retrieved from: https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/61d64d5f9d24da33de8c58ab/64bf151081834392394c6cbf_hi001v02_2021-2022%2BAmended%2BAnnual%2BPHA%2BPlan%2Bd2a.pdf.

- HUD’s HCV dashboard shows the upward trends in the number of leased vouchers and costs per voucher. In June, 2024, HUD announced new and more stringent requirements for PHAs to apply for shortfall funding in Notice PIH 2024-21(HA): https://www.hud.gov/sites/dfiles/OCHCO/documents/2024-21pihn.pdf .

- The trend in per-unit costs (Figure 2) is not driven by turnover among non-LIP participants. Data from the HCV dashboard show that HPHA’s estimated annual attrition rate was less than 4.5 percent during early 2021, versus 8.5 percent nationally.

- Data from the 2021 American Community Survey show that among very low-income households in Hawaii, the average monthly rent was about $1,330 for those living in their unit for longer than one year, compared to about $1,777 for those who moved in more recently.

- Turnham, J., et al. (2015). “Housing Choice Voucher Program Administrative Fee Study: Final Report.” US Department of Housing and Urban Development, Office of Policy Development and Research. Retrieved from: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3055223.

- The amount of time required per household could change as HUD and PHAs implement the Housing Opportunity Through Modernization Act of 2016, which is meant to streamline these administrative processes.

- Rosen, E. (2020). The Voucher Promise: “Section 8” and the Fate of an American Neighborhood. Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press.

- Economy, C., Finnigan, R., & Espinoza, M. (2023). “Using Emergency Housing Vouchers to Address Homelessness.” Terner Center for Housing Innovation, UC Berkeley. Retrieved from: https://ternercenter.berkeley.edu/blog/emergency-housing-vouchers-lessons/.